New regulations emphasize patient safety in the supply chain

|

| Photo by FUSE |

As Geisinger Health System of Danville, Pa., celebrates its centennial this year, its supply chain is evolving to become even more patient-centric.

To support the integrated system’s founding vision of excellence (“Make it Right, Make it the Best!”), Geisinger’s traditional supply chain is transforming into a care support services group by reorganizing and retraining staff to be more visible to and supportive of front-line care providers.

“Our mission is to return the front-line care providers to the bedside and minimize their need to perform any logistics activities thereby enabling them to work to the top of their clinical licenses,“ says Kevin Capatch, director of supply chain technology and process engineering at Geisinger.

You may also like |

| Supply chain focus shifts to clinical integration |

| Outpatient growth presents new supply chain challenge |

| Supply chain technology advances |

| |

To that end, Geisinger rewrote the job descriptions of everyone working in materials management and other supply chain functions — including laundry, patient transport, and mail delivery — to move supply chain management from “the traditional background support role to the forefront of care,“ Capatch says. Geisinger then launched a chartered program that puts its retrained “care support assistants” on the patient floor to coordinate all necessary supplies and equipment needed to support bedside care, freeing clinicians to focus on patients.

This reorganization is based on a 2010 internal study that showed that Geisinger inpatient nurses spent on average 20 percent of their time engaged in logistic tasks. These tasks include so-called “roundup laps“ where they look up patient orders and then collect the necessary medications, supplies and equipment needed for the patient.

In the pilot project, the care support assistants are trained in medication and materials management activities and learn the art of interpreting “nurse speak” — terminology that nurses use for specific medical devices and other patient care items, and translating those needs to the unique product identifiers required by the Materials Management Information System and the Electronic Health Record. The care support assistants work side by side with nurses to make sure they have everything they need for optimal patient care.

The pilot, which started in 2014 in one Geisinger hospital with four care support associates working across two shifts, seven days a week on its pilot floors, is already showing results, Capatch says. “We have impacted logistics time,“ he adds. “We are giving nurses back time and they are investing it with the patient on the floor.”

The Geisinger reorganization is one example of quiet changes happening in hospitals around the country that aim to improve patient care through supply chain redesign.

Meaningful use advances

More change is coming with the adoption of unique device identifiers (UDIs) for medical devices and associated technology to integrate medical device data into patient records and hospital data analysis.

“The driving trend I see is the importance of taking the supply chain and patient safety to the next level,“ says Jean Sargent, vice president of health care strategy and implementation at USDM Life Sciences. “But there are still a lot of roadblocks in the system. So many hospitals are focused on electronic health records (EHRs) implementation and meaningful use that it is difficult to get IT support and hours to work on supply chain systems integration and upgrading to new systems where UDI data is built in.”

Additional resource |

|

| This animated infographic from NSF shares handwashing information for the pharmaceutical industry. |

But Sargent and others say that is about to change with the final rule on meaningful use Stage 3, released on Oct. 6, 2015, by the Office of the National Coordinator on Health IT and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The new meaningful use rule requires hospital EHR systems to include UDIs within the Common Clinical Data Sets (CCDS), which are a summary of key information on the patient such as immunizations and allergies. Additionally, hospitals must be able to parse the UDI data and link to the UDI database maintained by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that allows it to conduct post-market surveillance on the devices, according to the rule.

What’s more, providers must be able to share all the CCDS information, including UDIs, when exchanging information securely with other providers, according to the rule.

Capturing the right data

The rule builds on a system launched a year earlier, on Sept. 24, 2014, when the FDA went live with a rule requiring manufacturers of Class III medical devices — such as stents and other high-risk implantable devices — to provide the UDI with each device. The FDA set up the global UDI database for device surveillance and post-market recalls.

Sargent says the new rule is important to drive adoption of bar code scanning and database updates to support the use of capturing the UDIs.

“Now that it is in the requirements for meaningful use Stage 3, IT will need to work more closely with the supply chain,“ she says.

Having UDI information in a patient’s medical record will improve patient safety, Sargent adds. For instance, a physician whose patient is experiencing complications from a recent heart procedure will be able to look into the patient’s health record and determine the medical device used in the original procedure to make sure there are no problems with that specific product, Sargent explains.

More broadly, hospitals and health systems will be able to use the UDI database to conduct comparative effectiveness research and notify patients in a timely fashion of any recalled products, she adds.

The addition of UDI capture as a requirement for meaningful use certification is a game changer, says Karen Conway, executive director of industry relations at GHX and chair-elect of the Association for Healthcare Resource and Materials Management (AHRMM).

“It’s going to be huge,“ Conway says of the rule. “Today, we often identify and describe products differently depending on what we are doing with the data — for example, for clinical or supply chain purposes. UDI gives us a great opportunity to create more consistency, accuracy and visibility around the products used in patient care by capturing the right data in our systems.”

Additional resource |

|

| This timeline from the Pew Charitable Trusts contains the dates for adoption of the various parts of the Drug Supply Chain and Security Act. |

Setting the foundation

Capatch says that the capture of the UDI, which Geisinger has been doing for years, is only the beginning. Health systems must be able to “consume“ the UDI in a relevant fashion — and that is where the work begins.

“The real change I see in the industry is now that we have this uniqueness — the UDI — we have what architects call a foundation to build upon,“ Capatch says. “An endeavor without a solid foundation never gets off the ground.”

With that uniqueness, systems must be built to support it and make it relevant. For instance, a supply chain manager may have a product that previously had latex that undergoes a refinement and now is latex-free. With a UDI database, the update on the product change to remove latex is immediately available to providers and materials management professionals. It may open up product channels for the manufacturers if it is a positive change, like the removal of an allergen such as latex.

“I don’t have to risk that my information on that product is outdated,“ Capatch says. “I will be able to interface systems and provide product updates in real time.”

Sargent says the ramp-up to adoption of both UDI and the database updates and bar code scanning necessary to collect the information may be daunting, but there are a few health systems working diligently to incorporate this into their daily routines.

“Health care is a vast industry,” Sargent says. “The adoption of the UDI will assist all in supporting a safe patient environment.”

Rebecca Vesely is a freelance health care writer based in San Francisco.

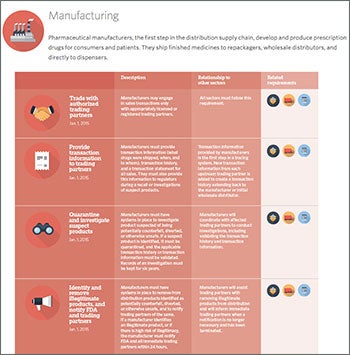

What the Drug Supply Chain Security Act means for health care

Hospital pharmacies also are seeing big changes in how they handle products in the supply chain because of a new federal law that went into effect earlier this year.

The Drug Supply Chain Security Act, signed into law by President Obama in November 2013, seeks to improve consumer protections by building a better system for detecting and removing potentially fake or contaminated drugs in the supply chain over the next decade.

The law establishes a national system to track and trace pharmaceutical products. Manufacturers, wholesale distributors, repackagers and many dispensers (primarily pharmacies, starting in July 2015), must provide key information about drugs in the United States, including who handled it each time it was sold in the domestic market.

The law aims to ensure the pedigree of drugs, says Marvin Finnefrock, vice president of clinical and purchasing services at Comprehensive Pharmacy Services (CPS), which manages pharmacies at 400 hospitals nationwide.

“The pedigree of the drug means how that drug is stored; did it sit in a hot truck for eight hours?“ Finnefrock says. “And how many hands touched it? Who purchased it?”

Before the new law went into effect, drugs could be bought and sold many times through secondary vendors, but today hospitals need a clear paper trail, and drugs are generally purchased through major wholesalers, he adds.

The law has complicated the vetting and purchasing of drugs that are in short supply, of which there are many today, Finnefrock says. Drug shortages are not new, but over the past five years or so the shortages are affecting supply chain management and patient care decisions.

Many of the drug shortages are for older generic drugs that companies have no incentive to produce, including some older antibiotics and injectables.

These shortages have resulted in more comparative effectiveness research into drugs to find comparable medications that are not in short supply, Finnefrock says. CPS conducts internal comparative effectiveness research on drugs when one in a class is unavailable, to find alternatives to present to clinicians.

“We are looking at patient-centered outcomes,“ he adds. “Unfortunately, many drugs that come to market don’t necessarily come with research on competing drugs.”

CPS also takes a second look at older drugs that may have fallen out of favor to see if they might work as alternatives to drugs in short supply, Finnefrock says. Factors considered include side effects, accessibility and costs.

For more information

The following resources were consulted for this article and offer valuable information regarding supply chain safety and complying with government regulations.

• Pew Health Group's report "After Heparin: Protecting Consumers from the Risks of Substandard and Counterfeit Drugs" addresses the implications to the United States of a globalized pharmaceutical industry.

http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/2011/08/12/pppinfographicwebversion.pdf?la=en

• Through International Operation Pangea VIII, The Food and Drug Administration this year took action against more than 1,050 websites selling illegal prescriptions and medical devices.

http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm451755.htm

• This infographic from Pew Charitable Trusts gives a timeline for implementing various measures part of the Drug Supply Chain Security Act.

• This table from the Food and Drug Administration outlines compliance dates for the Unique Device Identification final rule.

• The Association for Healthcare Resource & Materials Management gives tools to help supply chain directors promote the use of Unique Device Identification within their health care organizations.