Learning the truth about the 96-hour rule

When disaster strikes, every hospital needs a plan of action.

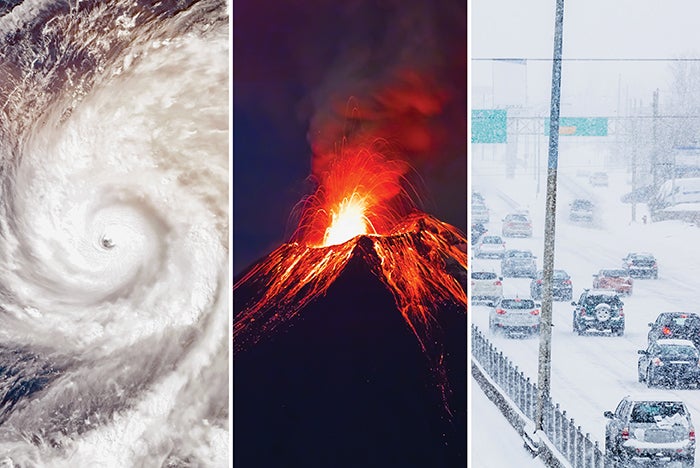

Images by Getty Images

When disaster strikes, every hospital needs a plan of action. Will it stay open indefinitely? Stay open for a defined period and then close? Close immediately?

It’s a nuanced and site-specific decision that requires collaboration between community leaders, emergency management agencies, public health entities and internal stakeholders.

Ultimately, it’s a decision that health care leaders can — and must — make based on what’s in the best interests of patients and the community-at-large as well as the feasibility of remaining operational.

Dispelling myths

Designing a hospital-specific 96-hour plan counters the incorrect assumption that all health care organizations must remain open and operational for at least 96 hours in the wake of an emergency or disaster.

While The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Conditions of Participation accreditation standards reference a 96-hour emergency preparedness plan, the reality is that each hospital’s plan may vary. This makes sense given the diverse nature of today’s health care organizations and the communities they serve.

The reason accrediting organizations want to see a 96-hour plan has always been for the health care organization to identify their capabilities based on a scale of 96 hours. This helps the organization identify the gaps, which helps them better understand when they may need to limit services or even evacuate if necessary.

An important takeaway: Although organizations must assess the first 96 hours and develop a plan, there’s no requirement for hospitals to have 96 hours’ worth of resources or to remain fully functional during the first 96 hours.

For example, a Level I trauma center may opt to remain open and serve patients indefinitely because it’s the major hospital in the community and has sufficient staff, physical space and supplies to treat all types of patients and injuries. However, the same may not be true for a smaller acute care hospital with limited clinical expertise, an orthopedic hospital providing mostly elective surgeries or a rural hospital that employs only a few nurses on-site.

The smaller acute care hospital’s 96-hour plan may be to remain open but only for stabilizing patients who will then be transported to a different facility. An orthopedic hospital’s 96-hour plan might be to simply cancel all pending surgeries, take care of existing patients for 24 hours and then close. Alternatively, a critical access hospital might close after 24 hours and then provide patients with transportation to the closest facility that remains open. Some hospitals may opt to close immediately and advise the public to call 911.

None of these options are “wrong,” and they all comply with 96-hour emergency preparedness requirements.

Creating a plan

With that said, deciding what to do in the event of an emergency is complex and has significant implications for patients, staff and the community. When a hospital stays open, it must be confident in its ability to serve patients despite real and potential barriers to care. This is a major responsibility. When a hospital decides to close in the wake of a disaster, it increases the load on surrounding facilities and can directly impact patients’ lives.

Assessing needs. While it may seem easier — and more straightforward for purposes of accreditation — to remain open and fully operational for 96 hours, the truth is that health care organizations become profoundly vulnerable to financial losses when leaders haven’t thought through this decision fully.

More specifically, when health care leaders insist on uninterrupted business operations following a disaster or emergency — and keep 96 hours’ worth of resources on-site even when this isn’t the most sensible or realistic option — they may experience the following:

- Food spoilage. Hospitals lose money that could be allocated elsewhere.

- Fuel spoilage. Hospitals incur unnecessary costs for additives to maintain generator fuel they may never use.

- Pharmaceutical waste. Some of this waste could be hazardous to the environment, and during an emergency, there may be no way to dispose of it properly.

Ultimately, health care leaders should base their decision about how to handle the 96 hours after an emergency or disaster on the following questions:

- What are the patients’ needs? How do clinical needs, patient severity, average length of stay and other factors affect the organization’s responsibility to remain open — and for how long?

- What are the community’s needs? Facilities managers should be at the table during these conversations to ensure that the organization can fulfill its promises and set realistic expectations based on the facilities’ capabilities. In what areas can the organization support other organizations, and in what areas will it need support from others?

- What is the most comprehensive and current list of consumables necessary to ensure a continuity of operations? What consumables (e.g., medical supplies, medical gases, pharmaceuticals, linens, food, potable water, non-potable water, fuel for emergency power and fuel for heating and cooling) does the organization use on a regular basis.

- When would replenishment be needed? Consider replenishment time frames with normal usage versus surge capacity.

- What is the plan for replenishment? For example, keeping 10 hours of fuel on-site and replenishing every 10 hours may make sense when an organization is located close to an oil refinery. However, oil delivery requires trucks and accessible roads, one or both of which may not be available in an emergency. What’s the backup plan? Could the organization rely on an alternative source of energy such as wind, solar or water? Can drones be used for certain types of supplies? Does the location of the facility affect its ability to acquire resources from outside partners?

- Can the organization conserve resources if needed? If so, what’s the plan to do that?

- What staffing challenges might the organization encounter? Can the organization realistically carry out a shift change, or might it need to use the same staff (e.g., if a bridge to the facility collapses during an earthquake)? If so, for how long can the organization leverage those same staff members without compromising patient safety and care quality?

The answers to these questions help health care leaders determine whether to stay open (and for how long) after a disaster or emergency. There will likely be multiple iterative conversations before arriving at a decision, and this decision could change over time, depending on community needs and internal resources.

Informing the public. An important part of the conversation about 96-hour emergency preparedness is how organizations communicate their plan to the public. In the hours and days following an emergency, it’s critical that people know where to go to get the care they need without wasting precious time and energy.

The time to communicate the organization’s 96-hour plan is before a disaster strikes. Health care leaders should let patients know whether and how long the facility will be open after an event occurs. It’s also helpful to let patients know the rationale behind the organization’s decision, especially if it plans to close at some point.

For example, leaders may want to convey that while the organization ensures high-quality care, it does not have the capacity to provide long-term support in the event of an emergency due to its location, access to supplies or physical space. These public relations considerations are an important component of any 96-hour emergency preparedness plan.

Facilities managers’ role. Facilities managers can assist with 96-hour emergency preparedness in the following ways:

- Reiterate the truth about emergency preparedness. There is no requirement for hospitals to have 96 hours’ worth of resources or to remain fully functional during the first 96 hours.

- Develop a current and comprehensive list of consumables along with a replenishment plan, when needed.

- Set reasonable expectations with community partners, emergency management agencies, public health entities, internal stakeholders and others in terms of the role the health care organization can play during an emergency or disaster.

Informed decisions

As today’s health care leaders look ahead, they must make informed decisions about whether and for how long to remain open and operational in the first 96 hours after a disaster and beyond.

No two organizations may handle this the same way, and there’s nothing wrong with that. When organizations put patients and their communities first, there is no wrong answer.

Facilities managers play a critical role in educating others about regulatory requirements, dispelling myths and setting reasonable expectations.

About this article

This is the first in a two-part article about 96-hour emergency preparedness. This piece introduces the concept of a 96-hour plan and dispels longstanding myths about stockpiling supplies and other resources. The second piece delves into technical requirements of emergency preparedness and how health care organizations can comply.

Chad E. Beebe, AIA, CHFM, CFPS, CBO, FASHE, is deputy executive director of regulatory affairs at the American Society for Health Care Engineering. He can be contacted at cbeebe@aha.org.