Working with local authorities on building projects

|

| Illustration by Kino Brod/Illustration Source |

A real estate development project is a large task for any health care organization. Before the construction work can even begin, organizations must navigate what is often a maze of governmental planning, review and approval requirements.

It’s a process that demands careful preparation and organization, especially for projects with a tight timeline or with rigorous zoning and local regulatory issues. Although real estate development can be an effective strategy to support an organization’s financial health, it is not a core focus for most hospitals, physician groups or other health care providers.

The approval process can be daunting, if not downright confusing, and the local politics can be time-consuming and full of potential pitfalls. However, health care organizations can prepare for the trials of working with local and state governments during major health care development and construction projects.

Understanding requirements

The first step in most health care development projects is identifying the development site. In some cases, this may be as simple as determining a footprint on an existing medical campus, or it may require selecting a new, undeveloped piece of land or even a redevelopment opportunity.

Each site is unique and two sites may differ widely in terms of the steps required to bring a project to fruition. For example, a site that is already zoned and approved for medical use should present a cleaner path forward than a site requiring a zoning change or a new piece of property without entitlements. In fact, the latter may require a series of public hearings over a period of months before a project can move forward, forcing a health care organization to consider not only location but also additional cost and delay when selecting a site.

IN BRIEF |

| • Real estate development projects require health care organizations to navigate a maze of local governmental entities. • Key areas that facilities professionals must consider are requirements, incentives, relationships and schedules. • Careful planning will enhance the goodwill of local communities and result in a timely project opening. |

Once the site is selected, the next step is understanding the applicable land use regulations. A few of the common issues to be addressed are maximum building height, lot coverage, minimum setbacks and number of required parking spaces. This essential threshold step requires digging into the municipal or county codes, and sometimes requirements imposed by regional and state regulations. There are even cases in which federal agencies may get involved, such as the Army Corps of Engineers (where the property includes wetlands) or the Federal Aviation Administration (where the property is located proximate to an airport and in a flight path). Completing this process early is helpful because some of these requirements may involve long lead times.

At the same time, health care organizations should work to understand how the various approval processes work. Specifically, this means mapping out the steps to secure all approvals and the required documents, submissions or meetings associated with each step. This will aid in creating a timeline that will determine when construction work may be able to start.

You may also like |

| Leasing health care spaces |

| Property portfolios for population health |

| Unlocking data from facilities portfolios |

| |

Today, much of this research can be conducted online, including reviewing the planning and zoning codes and identifying requirements that drive site and building design. However, when possible, it’s advantageous to contact the planning department of the governing jurisdiction to get a firsthand account of the requirements, fees and timelines, and to understand anything that may not be available online. Early communication with the local planning staff also offers an opportunity to introduce the project and establish relationships that will prove useful if the project hits any snags.

However, health care organizations should be wary of naively approaching top local officials too early. Without a thorough understanding of local politics, organizations that first approach a mayor or council president risk looking as though they are trying to force a project through the approval process from the top down, which may backfire at the city council or planning commission level. It’s usually best to start by working with local staff and elevate discussions only when necessary.

Identifying incentives

Tax incentive programs can have a significant impact on the total cost of a health care development project. Early in the research process, health care organizations and their real estate advisers should identify what incentives might be available for the site or sites they are considering. For some properties, there may be programs that would help reduce real estate taxes or personal property taxes, the latter of which often apply to medical equipment. Many jurisdictions offer construction sales tax exemptions to qualifying projects, and there also may be workforce development grants associated with hiring or training a certain number of employees.

When researching these programs, the city’s top local planning official may be able to share some information. But in general, the city or region’s economic development team — whether a department, economic development board or chamber of commerce — will be the best source of information. With the goal of attracting jobs and improving economic conditions in their communities, these groups routinely work with organizations that are considering new real estate developments.

Health care organizations should reach out to economic development leaders as early as possible in the planning process to ensure that they don’t miss any opportunities. Some health care organizations make the mistake of inquiring about tax incentives after they have publicly announced the development or it’s otherwise clear the project is moving forward. Because tax incentive programs often are structured as inducements to secure development and jobs, officials may be reluctant or statutorily unable to extend program benefits to a project that is already well in motion.

Building relationships

Another area where health care organizations may encounter challenges is in dealing with community or neighborhood groups that have an interest in a development site. In fact, these interactions are increasingly common as physician offices and outpatient provider locations become more prevalent in residential or suburban areas vs. medical campuses.

In many cases, community, neighborhood and homeowner groups don’t hold legal power to approve or deny a project, nor can they technically impose stipulations on things like parking and traffic flow. However, these groups are vitally important and should not be discounted. They may hold significant influence with the local officials who are responsible for approvals. And, if they are displeased with a project for any reason, they may be able to organize enough community opposition to have it delayed or denied, potentially damaging a health care organization’s relationship with the community in the process.

To avoid such conflict and build goodwill with future neighbors and existing or future patients, health care organizations should invest time early in the planning process to understand whether there are any local groups that may be affected by or concerned about a project. City officials often can give insight into such groups and may be able to make introductions so health care organizations can share their plans and listen to any feedback, questions or concerns. These interactions may be as simple as a couple of one-on-one meetings. Or, in the case of a controversial development, they may require community forums to allow neighbors a chance to offer opinions and input.

Often, health care organizations can alter their plans to make neighbors happy without affecting a project’s larger design, budget or timeline. For example, small compromises to the building’s signage or parking plan may help to reduce a development’s impact on the neighborhood and address issues that might otherwise cause conflict and delays in the approval process. Though these compromises may not be required by statute, they can help to facilitate project approvals and show the community that the health care organization wants to be a good neighbor.

Managing the schedule

Depending on the site, the approval process for a health care development can last anywhere from a couple of months to more than a year. Each municipality or county will have a multistep path to gain approvals and, in most cases, each step must be accomplished in a required sequence. This path is usually date-specific, meaning a health care organization should be able to anticipate based on when its project proposal is submitted, the week or month it will go before the planning commission, the week or month it will go before the town council, and so on.

Managing these deadlines appropriately can mean the difference between completing a project on time or falling months behind schedule. For example, the town of Jupiter, Fla., only accepts site-plan submissions on the second Monday of the month. Missing that deadline automatically pushes a project one month later for review by the planning commission, and every subsequent step is affected. This kind of scheduling management can be critical to securing governmental approvals in a timely manner.

Throughout the approval process, health care organizations can expect to receive questions or requests for additional detail. The relevant governing body may provide a set time frame by which a response is due to keep the approval process on track. If the response is late, it could delay the rest of the process, sometimes even longer than just the next meeting date. For example, some municipalities meet on a monthly basis and their meeting agendas fill quickly, so missing a deadline to go before the planning commission in February could delay a project by more than a month if the commission’s March or subsequent agendas are already full.

Additionally, when regional, state or federal approvals are required, there may be a set order in which those approvals must be obtained. For example, if a city’s water and sewer service is supplied by a regional authority, the project may need approval for its water and sewer plans before the site plan can be approved. This is why the initial research and planning stage is so important — it allows visibility into the full process so organizations can plan exactly what they need to do and when they need to do it to begin construction.

Closing out

After the approval process is complete and construction is underway, there are still a few things organizations must do to finalize their work with local governments so the project can be completed on time and the facility can open its doors.

Health care organizations must process all documentation with jurisdictional agencies and local utility companies to close out all open permits. This will include inspections during and after construction to ensure that everything from the building’s structural components to its electrical and plumbing work are safe and code-compliant.

Typically, the last step in this process is working with local officials to obtain final inspections and receive certificates of occupancy for the building’s shell and interior suites. However, there also may be post-occupancy requirements imposed during the project approval process, such as a requirement to provide future traffic studies once a project has been open for a designated period. And at this stage, projects seeking Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification will finalize the LEED review process.

Finally, organizations should confirm that they have obtained all necessary business licenses and that any applicable operational fees have been paid to the city and county. Verifying these final requirements and ensuring that there are no loose ends will allow the organization to turn its full attention to the future and providing quality and cost-effective care to its patients.

A health care construction project is a big task with many incremental planning and approval requirements along the way.

By taking time to understand and map out the required tasks, timelines, potential obstacles and financial incentives, organizations can feel confident that they are on the right track to realizing their goals.

Brian C. Cich is executive vice president at Rendina Healthcare Real Estate, headquartered in Jupiter, Fla. He can be reached at bcich@rendina.com

Coordination is key in dense, urban environment

|

| Graphic courtesy of Rendina Healthcare Real Estate Developing a medical facility in an established and dense urban environment generally amplifies the complexity of the project, the amount of governmental interaction and the number of required approvals. |

The project site for the ambulatory care facility Barnabas Health–Bayonne is located along one of the busiest thoroughfares in downtown Bayonne, N.J., within an area targeted by the city for redevelopment. When the facility opens, it will include an emergency department, imaging center, retail pharmacy, pediatric center and more.

To bring the project to fruition, New Jersey-based health system Barnabas Health partnered with an experienced health care real estate firm, which identified the site and purchased the land.

Developing a medical facility in an established and dense urban environment generally amplifies the complexity of the project, the amount of governmental interaction and the number of required approvals. The Bayonne site also contains several older, mixed-use commercial and residential buildings that must be demolished as a part of the project. And it will include a multistory parking structure on adjacent land owned by the city.

These circumstances required numerous approvals on the local, regional and state levels, including the creation and adoption of new resolutions and ordinances by the city government. In addition, the residential and commercial neighbors had to be kept informed.

With the input and assistance of the project team, the city adopted formal legislation to designate the area for redevelopment, and the health system’s real estate partner was formally named as the redeveloper. The city and project team worked to draft and adopt the legislation required to abandon a public roadway traversing the project site, and a ground lease was executed with the city to lease the property under the proposed parking structure. The complexity of the project required meticulous planning, persistent supervision and regular flexibility.

Property owner complicates development process

|

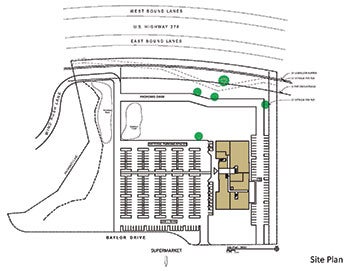

| Graphic courtesy of Thomas & Hutton The Bluffton (S.C.) Medical Campus is located in a shopping center anchored by a prominent supermarket chain, adding another layer of complexity to project negotiations and approvals. |

The 60,000-square-foot Bluffton (S.C.) Medical Campus was a unique project requiring multiple levels of approval and complex negotiations. Hilton Head Hospital partnered with a leading health care real estate firm to complete all facets of the outpatient facility, from site identification and purchase, through completion of construction and delivery of the tenant suites. The real estate firm worked with a local broker to determine the best location for its hospital client and entered into a contract to purchase the land.

The selected property was located within a retail shopping center anchored by a prominent supermarket chain. The supermarket chain retained extensive rights to approve all future uses and development in the center, making negotiations and approvals even more complex than generally experienced with other development projects. In addition, the development required a Certificate of Need (CON) from South Carolina’s Department of Health and Environmental Control, and approval from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers because the site contained federally protected wetlands.

The hospital’s real estate partner handled negotiations with the supermarket chain while working with local consultants and a regional architect to prepare all materials required to support the requested CON and all federal, state and local approvals. The process included numerous meetings with government officials at all levels as well as several public hearings. With the complexity of the project and approvals required, project development could have taken up to four years. However, with good planning and constant oversight, all approvals were secured and the facility was constructed and opened in slightly more than two years.