The future is now

Health care industry professionals who believe the political outcome of the reform debate alone will have a dramatic influence on the future of design and construction of health care facilities are sadly mistaken.

Health care industry professionals who believe the political outcome of the reform debate alone will have a dramatic influence on the future of design and construction of health care facilities are sadly mistaken.

The mid- and long-term future for design professionals, their clients and communities will be determined to a far greater extent by trends that are already underway and which, for better or worse, will be modified only minimally by the outcome of the political process.

For those among us, therefore, who long for a return to the robust days of the middle of the last decade, there is little to cheer about. In addition to the established paradigms of maximizing efficiency, flexibility and factors leading to quality of care, the next paradigms may see a chasm: one side promoting high-acuity (tertiary/quaternary) care in major urban medical centers and the other side promoting lower-acuity (primary) care in retail/residential settings.

Left out of this scenario would be local unaffiliated community hospitals that will continue to face financial challenges borne of market share loss to the two polar extremes previously noted. For those who, through great effort, are to continue operating successfully, a key element of that fiscal responsibility is likely a dramatic, long-term reduction in major capital and operational spending, particularly on inpatient care.

Ten key influencers

Let's review the key trends that may determine our collective future:

1. Fall in reimbursements. Continuing downward pressure on Medicare reimbursement likely will narrow operating margins. Pressure will exist for commercial payers to lower rates to the Medicare standard, and as a result of increasingly scarce excess revenues, capital may be harder to access, or even unavailable. The bottom line is that the current hospital model may not be viable under pure Medicare-reimbursement levels.

Falling Medicaid-reimbursement levels are equally troubling. Aside from inevitably raising the specter of insolvency among many current providers of inpatient care, this resulting predictably diminishing pool of disposable income likely will lead to continued deferred or delayed inpatient projects. For those projects that are funded, highly efficient, productive and economical inpatient deÂsign will define the new design imperative.

2. Focus on transparency and quality. As American College of Healthcare Architects (ACHA) certificants and colleagues heard from Abby Block of Booz Allen Hamilton, McLean, Va., and from Ken Kaufman of Kaufman Hall, Skokie, Ill., at the 2010 ACHA/American Institute of Architects (AIA) Summer Leadership Summit, there likely will be payment disincentives for preventable hospital admissions and readmissions, as well as for avoidable adverse health outcomes, the so-called "never-events" list. This probably will lead to a reassessment and reinvention of the overall patient process and experience, and suggests continuing downward pressure for an average length of stay to be reduced to generally accepted best practices.

The focus on transparency will create empowered consumers at all levels, placing demand on facilities to exhibit maximized efficiency and minimized facility-related negative distractions that potentially diminish quality, safety and the overall patient experience.

While the intent is to reward the delivery of high-quality care, the pressures in the market converge to create the potential for payers to act on a statistical distinction that lacks a clinical difference.

Arguably, hospitals reporting quality markers in the 90th percentiles could be ranked differentially according to a statistic, but clinicians point out that there are potentially little-to-no practical clinical differences between facilities reporting quality indicators at that level. Consequently, facilities will experience increasing pressure to take full advantage of every aspect of design that research suggests might contribute to a better statistical outcome on quality.

3. Importance of information technologies (IT). Financial incentives to adopt the meaningful use of electronic health records (EHRs) predict their greater use in measuring performance in the health care system.

The patient-centered medical home model uses EHRs to link primary care with the remainder of an integrated care system. And just as electronic delivery of information (eHealth) permits a transition from paper-based records to the EHR, there is growing evidence that mobile health (mHealth) will supersede it.

mHealth is most commonly used in reference to using mobile communication devices, such as mobile phones and personal digital assistants, for health services and information. Not only will IT be central to health care delivery, it will foster far greater ability for "virtual" delivery, independent of traditional care settings.

While the industry will be challenged to adapt to a radically upsized IT operating environment, it also will be challenged to make the transition from using IT primarily for patient-data storage and billing to using it as a central component of business development and a key weapon in capturing market share.

4. Looming challenge of staff shortages. There is a predicted shortage of nurses in all 50 states by 2015. Physician shortages likely will be as widespread and potentially even more severe, especially in the near term before schools can respond to the increased demand for care by the newly insured.

These shortages, as well as those of other skilled professionals, negatively impact care not only in hospitals, but also in long-term care, ambulatory care and a broad range of other settings. Efficient delivery of services will be more important than ever, and designers must be attentive to the impact of travel distances, sight lines and presumptions of fewer staff members performing many tasks. In many cases, this will require employing eHealth and mHealth technologies.

The challenges of staffing traditional health care delivery also may prove to be one of the strongest catalysts in the development of alternative-delivery models that will take full advantage of allied health personnel instead of the traditional physician and nurse staff models.

5. Accelerating migration of care to the community and the home. And just as eHealth and mHealth will permit more efficient delivery of care inside the hospital, they will perhaps be of greatest long-term impact outside the hospital.

The marketplace has grown accustomed to movement of primary care into retail settings such as the Target Clinic and CVS MinuteClinic. And Walmart, with the marketing and buying power of the world's No. 1 retailer hosting 130 million shoppers every week, has begun to move aggressively into primary care.

The retail environment, however, is but one step in the migration of care away from traditional settings. Eric Dishman of chip-giant Intel's Digital Health Group leads a well-refined effort to provide viable "aging in place" settings utilizing computer chips embedded in household items, permitting real-time monitoring of daily activities of an elderly or infirmed individual. The Garfield Center of the Kaiser Permanente organization is exploring the use of Wii™ micro-technologies in home-health clothing that would allow remote monitors to know when a home health patient has fallen and how hard they landed.

As technology continues to extend safe, reliable care into low-cost retail and home-based settings, the "facility" response to the health needs of many aging baby boomers may, indeed, not be the settings of their parents' generation.

6. Imposing legacy of obsolescence and poor location. As noted previously, many health care delivery trends are driven by technology — linking consumers and caregivers to vast databases of information — in ways that we can only imagine. Irrespective of facility location, for many consumers, the link to health care delivery may be "virtual."

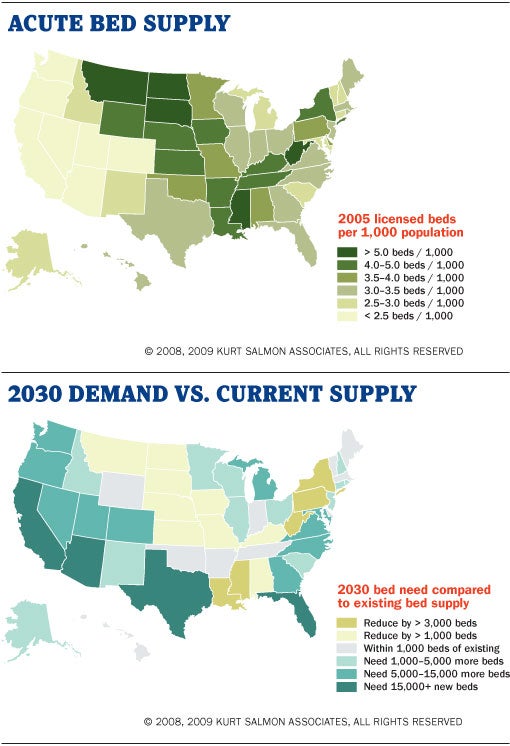

There are, nevertheless, geographic implications on health care delivery in the near future. The current supply of care beds is not where the projected demand for those beds will be in the coming decades. In a world of diminished reimbursement with pressure to move the locus of care away from the inpatient setting as existing inpatient facilities continue to age and as pressure grows for new inpatient facilities in areas with fewer beds, a key concern relates to capital-debt management. How will older facilities retire their debt and how will new facilities propose to manage the debt traditionally ascribed to such projects?

It may be in the areas tentatively targeted for new inpatient facilities that the industry will experience the greatest pressure to explore new care delivery models that reduce and effectively manage the need for capital to build new health care projects.

7. Changing structure of the medical care model. If all reimbursement, including commercial payers, went to the Medicare standard, many if not most hospitals couldn't stay open and only a few of the largest systems would survive. Others would be cannibalized or absorbed for volume to cover overhead and fixed costs. The future of smaller (independent) organizations is uncertain. Therefore, the amount of capital investment in independent community hospitals likely will remain greatly diminished.

As has already been suggested, what is needed is not a continuing emphasis on more efficient design; what is needed is a new delivery model that recognizes that unless the promotion of health can be properly prioritized in this country, the country may never be able to build or staff or pay for enough medical care.

8. Increasing priorities of promoting health and reducing demand for medical care. The three risk factors of tobacco use, low activity and poor diet will play increasing roles in the focus of the health care delivery system and of the facility response to that system.

According to C3 Collaborating for Health, based in London, those three risk factors account for four chronic diseases (cardiovascular, type 2 diabetes, cancer and chronic lung disease) and approximately 50 percent of deaths worldwide.

Christine Hancock, founder of C3, notes that "architects, urban planners and transport engineers (among many others) can create environments in which healthy choices are easy choices."

Notably the AIA Academy of Architecture for Health revised its bylaws this year to reflect a mission not only centered on health care facilities, but also on creating healthy communities. In addition, the AIA launched late in 2010 the America's Design and Health Initiative whose mission is to focus on ways design can contribute to people's health and well-being and, by extension, reduce their demand for medical care.

9. Lingering confusion by the capital markets. As noted previously, a looming challenge is what to do with current capital debt covering obsolete facilities.

The subsets of this challenge are twofold. The first issue is how to finance new capital projects in a difficult economy when the impact of reform legislation is unclear and the traditional sources of revenue to retire debt are on a steady decline. The second issue is how to finance new capital projects when there is widespread agreement that the current medical care delivery model is changing significantly into a new delivery model that still is undefined, but will surely reflect a greater emphasis on health vs. medical care and a growing discomfort with the traditional emphasis on inpatient care. Not surprisingly, it is likely that debt-retirement planning will take on shorter horizons with the goal of beating the ever-accelerating obsolescence curve on technologies and other care delivery modalities.

Complicating this factor in an industry that traditionally is seriously obsessed with its technology is the harsh reality that the innovation phenomenon for technology, including medical technology, often is not linear and, therefore relatively difficult to predict.

Magnitudes of change and rates of change are nearly impossible to anticipate properly. One possible impact for design and construction professionals will be smaller-scale projects that have shorter useful lives. One other possibility, at the other extreme of the planning horizon, is that designers will be asked to provide facilities characterized by excessive flexibility that allows them to be relatively easily and quickly converted to an alternate use, thereby extending the facility life and the period for the retirement of any original and continuing capital costs.

10. Growing concern about health care's impact on national security. The military sector of the Soviet economy became proportionately too large and threw the Soviet economy seriously out of balance. All nations have the same vulnerability of one sector getting out of control and upsetting economic stability. In the United States, some health economists believe the window of imbalance is when any one sector reaches 20 to 25 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP), and health care as a percent of GDP nears 18 percent. Health care has the potential to undo or seriously interrupt the rest of the economy so, if it is allowed to continue to grow as a percentage of GDP, it deserves the highest priority and attention of lawmakers and planners alike.

More with less

In summary, the health care facility design and construction market in this era of restructuring likely will be characterized by the following:

- Deferred and delayed inpatient projects, particularly in the community hospital segment of the market;

- Dramatic growth in retail and home-based care delivery — little of which taps the skill sets of the firms and individuals who traditionally have focused on inpatient care and hospital-based ambulatory care;

- Demand for maximized efficiency in those inpatient settings that are funded — focusing on the cost of people over the life of the building;

- Focus on research-driven planning and design that responds to the demands of a particularly well-informed client; and

- Preoccupation with quality, as transparency begins to shape reimbursement, operations and reputations. HFM

A. Ray Pentecost III, Dr.P.H., FAIA, FACHA, LEED AP, is the director of health care architecture for Clark Nexsen, Norfolk, Va., and was the 2009 and 2010 president of the AIA Academy of Architecture for Health (AIA/AAH). He can be reached at rpentecost@clarknexsen.com. Peter L. Bardwell, FAIA, FACHA, was 2008 president of the AIA/AAH. His e-mail is pbardwell@bardwellassociates.com. Both authors serve on the American College of Healthcare Architects' board of regents and the opinions expressed in this article are their own.

About this series...

"Architecture+Design" is a tutorial published quarterly by Health Facilities Management magazine in partnership with the American College of Healthcare Architects (www.healtharchitects.org).