Four key design strategies

The second largest facility of its kind in North America, the new Calgary Cancer Centre in Canada will support patients and their families on their cancer journeys with a large central courtyard and uninterrupted views of the Rocky Mountains. The design enables the integration of treatment, education and research into a comprehensive health campus.

Image credit: NormLi – DIALOG, Stantec and PCL

A growing body of research points to the unique edge offered by design in curbing operational costs and advancing positive patient and resident outcomes for health organizations. The combination of architectural design and clinical planning is a neutral, resourceful and mighty force that can propel advancements in health care delivery.

Through this, health care providers can overcome the social, economic and political barriers and arrive at a system that is financially alert, operationally efficient and socially responsive by design.

To create these environments to surmount the pressing challenges facing health care in the 21st century, however, long-held assumptions of what is important in health care facilities must be challenged.

Supporting the mission

Set out below are some of the ways in which today’s health organization’s can support their mission by design. Specifically, when clinical planning collaborates side-by-side with architectural and evidence-based design.

1. Designing facilities as epicenter’s of health information can minimize silos between education, prevention and treatment create effective health systems. Treatment has been a core tenet of the traditional health system where most patients are seeking immediate and urgent care. With reactive treatment putting the largest strain on our systems, creating places for communities to receive health education, preventative support and reactive treatment changes our interaction with health and allows facilities to prevent, maintain and only if needed, treat.

According to the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, chronic conditions like heart disease, cancer and diabetes are responsible for the majority of deaths in America. With the majority of health costs attributed to such illnesses worldwide, a proactive health care model by design can reduce long-term costs and improve quality of life for patients, residents, staff and visitors. While real-life examples of the return on this emerging philosophy are limited, we are seeing first-hand that the number of health care facilities calling for a proactive health care model by design that can reduce long-term costs and improve quality of life for patients, residents, staff and visitors is increasing dramatically.

2. Combining evidence-based design and clinical planning with big data to modernize facilities efficiently while saving money. The advantages of co-developing operational plans, functional programming and physical facility design cannot be underestimated. While baby boomers are set to become the largest consumer demographic of health care services, the health care labor force struggles with a growing average age of health care providers with scare replacement. With technological innovation costly and changing at a rapid clip, is it the best way to invest?

The redesigned McCaig Tower at Foothills Medical Centre in Calgary, Canada, provides a 10 percent increase in surgical capacity, adding to the 17,000 surgeries performed annually.

Photo credit: John Gaucher/DIALOG

Designing physical spaces in support of the unknown, or future proofing, solidifies a health care organization’s value in their community with fewer risks and regardless of how quickly demographics and technology change. Curtailing long-term operational and financial inefficiencies can be achieved through evidence-based design in direct collaboration of clinical planning.

Over the life span of an acute care facility, construction costs can represent less than 7 percent of total costs, while operations can represent 93 percent. It is little wonder that health care administrators are looking for new and creative ways to reduce operational costs.

In one study published by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, the implementation of interior healing gardens, noise-reduction measures, large windows and decentralized nursing stations led to reduced staff turnover and medication costs, where incremental costs incurred were virtually recovered after one year with significant financial benefit accruing yearly. Further, as Bertalan Mesko, M.D., and Diana Anderson, M.D., have written in The Medical Futurist on combining evidence-based design and clinical planning with big data to efficiently modernize hospital facilities around the globe, “adequate hospital design could accelerate our journey into 21st-century healthcare ..."

3. Creating public realms with dignity at the core to enable health care organizations to be their community’s champion for healthy living. Over 700 peer-reviewed articles document a study for The Center for Health Design that points to a significant correlation between unanimated environments and negative outcomes, including elevated blood pressure levels, anxiety and delirium, and increased consumption of pain medication.

This is no fault of the hospital system, however. Escalating operational costs has led to the investment challenges in capital infrastructure to enable health care facilities to foster healthy environments. This contradiction plays an unnerving and well-documented role in the performance of staff spending the longest hours of all in these spaces.

From the complex care perspective, American seniors fear moving into nursing homes, with an overwhelming majority of their children concerned for the wellbeing of parents. The often-stabilizing forces of community and home can be integrated into health care facilities to advance healing and wellbeing through connecting health with life. Promoting healthy living while adhering to complex health care functions like infection control standards is possible when a collaborative and carefully mapped out design and planning approach is established at the very beginning.

Breathing life into a building’s exterior with access to nature, public transit, cycling and walking routes and community is the steadiest way to promote healthy living. Activating a public realm gives patients, residents, staff and visitors access to fresh air, natural light and flora. This is increasingly viewed less as a nice-to-have but a must-have.

According to a study for the International Academy for Design and Health, prolonged exposure to natural elements leads to lower doses of pain medication, fewer post-surgery complications and higher job satisfaction. On the inside, it is well known that a cognitive mapping system reduces anxiety, confusion and frustration. While reducing unwanted stimulation like noise and disruptions is common in design today, maximizing desirable passive stimulation is not but it can be highly beneficial in designing healthy environments. Academia has long pointed to studies where patients with direct and regular access to sunlight and nature heal faster with fewer complications and see similar outcomes with direct and regular access to nature scene visuals.

4. Seeking commercial and community partner collaboration to manage shrinking funding and increasingly unique health needs. Facilities are taking care of people with more complex needs than 30 years ago and alongside waning access to health care providers. While the demand for and utilization of health services varies greatly across demographic groups, an Institute of Medicine study reveals that the demand for services for older adults will rise substantially in the coming decades, with more than one in four expected to be in fair or poor health, putting increasing pressure on health care budgets and on the capacity of the health care workforce and organizations to deliver those services.

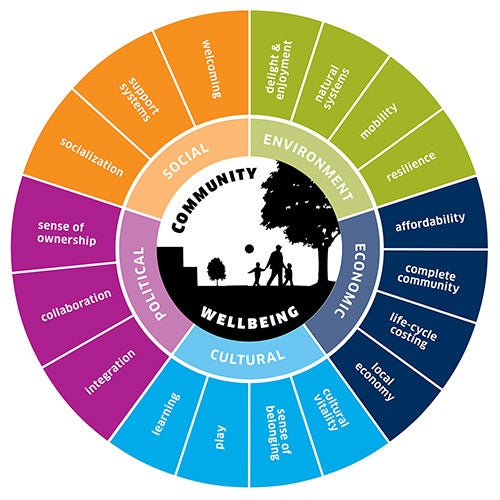

Adopting a health care model comprising community, retail and educational touch points allows an organization to withstand funding and staffing challenges while providing an all-encompassing approach to societal health and community wellbeing. Health care professionals in America are increasingly running clinics, urgent care facilities and freestanding emergency rooms or "micro-hospitals" in high-traffic locations like malls, grocery stores and pharmacies.

In response, traditional health care facilities can keep pace and relieve the demand burden by adopting retail systems to curb operational costs by making pharmaceutical and wellness offerings accessible on-site to patients, residents and their families. Further, creating health environments to encourage family participation can help prevent isolation and bring in support to staff. This means creating spaces for recreational activities, education and learning, overnight accommodation and are friendly to children and animals.

While reaching out to the community to coordinate on direct services is an emerging development, real-life examples are few, but the majority of health care organizations looking to redesign or build a new facility are being widely encouraged to adopt an all-encompassing model if they are not asking for it on their own.

Health care organizations have untapped and mighty resources in neighbors and community partners. As we begin the narrative for the third millennia, we are betting that collaboration between cities and hospitals, much like clinical planners and architectural designers, will be the ultimate remedy.

Ronald McIntyre, Diego Morettin and Lynn Webster are architects and health care design experts at DIALOG, a fully integrated multi-disciplinary design firm with studios in San Francisco; Toronto; and Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton, Canada. They can be reached at rmcintyre@dialogdesign.ca, dmorettin@dialogdesign.ca, and lwebster@dialogdesign.ca.