A closer look at U.S. health care infrastructure

Given the size and scope of the country’s health care infrastructure and its life-saving and health-promoting mission, it’s no wonder that its condition and ability to function at peak performance is a vital national priority.

With 5,627 registered hospitals in the United States and a total of more than 900,000 beds and a combined budget of nearly $900 billion, this vast system provides a fabric of buildings, engineered systems and technologies serving the nation’s well-being and economic strength.

This does not include an estimated 2,800 retail health clinics operating in the U. S. by the end of 2017, a number that is expected to grow.

Recognizing these facts, the American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE) and the American Institute of Architects’ Academy of Architecture for Health have released an ASHE monograph on the “State of U.S. Health Care Facility Infrastructure,” which has been excerpted for this article.

Condition of facilities

The overall condition of America’s health care infrastructure varies widely. Hospitals with strong market positioning and forward-looking leadership have invested in maintenance and modernization, while some hospitals in struggling communities have been unable to keep up.

Two key metrics of health care facility condition are the age of plant (AoP) and the facility condition index (FCI).

The AoP is not a direct measure of physical age; rather, it is a financial ratio that measures how well a hospital is keeping its facilities up-to-date. The ratio is calculated as accumulated depreciation over depreciation expense. This AoP metric is reported across several facilities, and its median (to correct for extreme outliers) is published. The resulting median AoP score allows the field to understand the general state of hospital infrastructure for any given time period and allows for tracking of patterns across years.

For example, the median average age of plant for U.S. hospitals in 2015 ranged from 10.78 to 11.48 years (depending on publishing source), compared with 9.8 to 9.96 years in 2004, and 8.6 in 1994. This increase in median average age of plant of nearly three years over the past two decades indicates that hospitals, in general, have struggled to raise the capital needed to keep their facilities up-to-date.

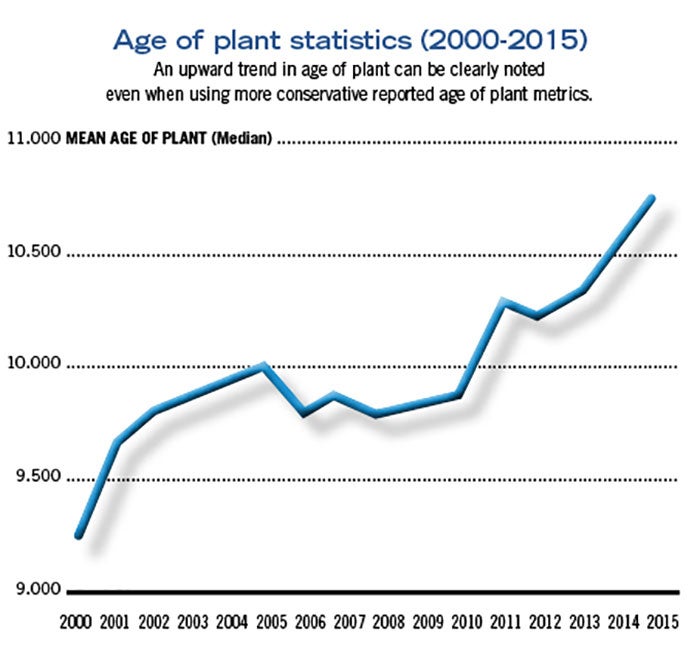

This upward trend of AoP can be clearly noted, even when using the more conservative reported (lower) age of plant metrics, as demonstrated in the graph on Page 20.

Specifically, the graph illustrates the year-to-year change for the calculated age of plant metric, where the y-axis represents the age of plant (reported as a median), the x-axis represents the reported year, and the line illustrates each data point connected. The upward trend is clearly visible, and when evaluating the difference between AoP in 2000 compared with the most recent AoP score for 2015, the difference is statistically significant, which translates to a moderately strong effect on AoP across time and lends credence to the assertion that U.S. hospital infrastructure may benefit from investment.

While the median AoP is a reasonable surrogate for the condition of health care facility infrastructure, most health care organizations conduct detailed facility condition assessments. These assessments provide specific information on deferred maintenance requirements and their estimated cost. These data are used to calculate the most common metric for measuring facility condition, the FCI. The formula for FCI is the cost of repairing a facility over the cost of replacing it.

ASHE Resource |

| State of U.S. Health Care Facility Infrastructure |

|

|

Unfortunately, comparative FCI data are not available because the FCI is most often used as a benchmark for health care facilities, rather than a reported and archived metric. Given that there are many factors that influence FCI (e.g., geographical and demand-based differences in market costs for repairs, subjective assessments of when repairs should be made), this metric often serves an in-house purpose and is not compared across facilities from different regions.

In practice, most consultants and health care facility leaders agree that buildings with critical functions (e.g., hospitals and surgicenters) should aim for FCIs of 0.05. For other, less critical buildings (e.g., outpatient clinics and administrative offices), the FCI target is closer to 0.10.

An FCI of 0.15 means the deferred maintenance costs equal 15 percent of the cost of totally replacing the facility. For these facilities, systems and components — such as panels, pipes and wiring as well as patient care systems like medical gas — may be as out of date as the physical structure (making it nearly impossible to find replacement parts because they are no longer available). Or, at the least, systems with medium-to-long life expectancies — such as mechanical, vertical transportation and roofing — have exceeded their useful life.

When a facility is unable to keep up with maintenance needs, the risk of failure increases. For example, one Midwest hospital deferred maintenance on an aging elevator system to save money. When the elevator suddenly stopped working, the consequent financial damage and lost productivity was many times greater than the cost the hospital would have incurred had it not deferred maintenance on that elevator.

In fact, one analyst calculated that waiting to replace a part or system until it fails will end up costing the organization the expense of replacement squared. For example, if a hospital decides to defer maintenance on an aging water heater to save $500, it may end up owing $250,000 when the water heater leaks through the floor and damages adjacent floors and walls.

This relative deterioration of health care facilities seems to be becoming a national concern, as one-third of chief financial officers (CFOs) responding to a 2010 survey conducted by the Healthcare Financial Management Association reported that their hospitals were in worse condition than 10 years ago. Furthermore, half of the CFOs surveyed reported that their infrastructures were deteriorating faster than they could make capital improvements.

Capital allocation

According to ASHE’s Healthcare Executive Leadership Council, most health care organizations develop sophisticated multiyear plans to determine where their capital will be used. Some key factors used to develop those plans include:

Condition | Major health care organizations measure the condition of their facilities regularly. While the most commonly used measure is FCI, some organizations simply create a list of systems prioritized by the urgency of their replacement. Often, these assessments are enhanced with sophisticated analytics that take into account the useful life expectancy of equipment, maintenance records, consequences of failure, cost of replacement and other factors.

MISSION | Some capital allocations support the mission of the organization rather than alleviate condition problems. For example, a hospital located in an area with an aging population may decide to build a skilled nursing facility to serve the community.

Potential return on investment | The likely return on the capital allocation can play an important role, as well. For example, sometimes investments in energy efficiency can rapidly offset the investment. A large academic medical center in the Midwest, for example, used the energy savings from a major upgrade of its plant to pay for $50 million in renovations to other facilities.

Market needs | Consumerism is about meeting patients where they are. These changing markets change strategies and, as a result, capital priorities. For instance, the vast majority of one health system’s capital investment is going into outpatient areas.

Brand image | Many hospitals strive to create facilities that cultivate feelings of confidence, expertise and compassion. A building’s layout, interior design and architecture have been shown to contribute as “intangibles” alongside clinical care.

Renovation investments

Primary motivations for investments in renovation projects include the following:

Hospital modernization | Many older hospitals have surgical and diagnostic/treatment areas that do not meet current practice standards for patient safety and infection control. Data show that rural hospitals and hospitals with fewer than 400 beds are slightly older, on average, than other hospitals, and their quality scores are slightly lower.

Bed modernization | Many aging hospitals either have an inadequate number of functioning, code-compliant patient rooms, or do not meet contemporary standards for providing single-patient rooms. Bed shortages also can put undue loads on emergency departments, which must hold patients until beds are available.

Resilience | The recent increase in frequency of adverse weather events and other natural disasters (e.g., floods, hurricanes and wildfires) leaves many hospitals vulnerable. Many health care buildings in areas prone to seismic events are not adequately prepared if constructed prior to current building codes.

Life-safety systems | Many older hospital buildings may have inadequate life-safety infrastructure to accommodate the new, more acute nature of hospital care. The Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals on behalf of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, announced the addition of 21 elements of performance to its life-

safety requirements for hospitals in early 2017. These new requirements, which include having sprinklers in closets and ensuring that oxygen tanks are stored in locked enclosures, will increase pressure on hospitals with systems not currently up to these standards.

New construction investments

Key motivations for investments in new construction projects include the following:

Population health initiatives | These initiatives aim to make health care available outside of the hospital and underscore the increasing need for freestanding structures that serve unique, timely, dual-function and innovative health purposes. These include structures that function as wellness clinics, fitness centers, immunization clinics, family teaching health hubs with grocery stores and cooking centers, and other health-promotion facilities.

Ambulatory care | Advanced health care systems recognize that overnight stays in hospitals are not only costly but, in many cases, unnecessary. Consequently, these organizations are increasingly building facilities to accommodate the growth in outpatient services, such as same-day surgery centers.

Mental health | The last several decades have seen the deinstitutionalization of the mental health population. Federal and local governments have cut mental health funding and closed mental health facilities, yet research has shown that mental disorders, particularly dual-diagnosis disorders, top the list of the most costly conditions in the United States. This news, coupled with the recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report that cites a 137 percent increase in drug-related deaths and a 200 percent increase in opioid-specific related deaths, clearly illustrates a need for additional mental health care.

Safety net clinics | Many public and private clinics serving low-income patients provide essential community health and primary care services while receiving marginal reimbursement. These facilities rely on payment sources that are often complex and difficult to navigate to keep their doors open. Given the increased pressures to provide the most affordable care for the growing disadvantaged population, it is reasonable to expect a greater need for these types of treatment facilities.

Indian Health Service | The infrastructure supporting the provision of health care services to the Native American population is sorely inadequate. The Indian Health Service, mandated by treaties following the dislocation of Native Americans more than a century ago, serves 2.2 million individuals. A 2014 Department of Health & Human Services report found that “outdated and insufficient buildings and equipment” threaten the quality of care for this population.

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facilities | Many veterans encounter unacceptable waits for services, some of which are due to inadequate facilities. Recent data show that some health care provision quality measures at VA facilities continue to worsen, including growing rates of infections related to catheters and rates of in-hospital complications. Greater investment in VA facilities would improve health and care for the nation’s veterans.

Responsible investment

The infrastructure of U.S. health care is not in critical condition, but it is aging. As with anything that ages, it takes more resources to keep existing facilities in top working order. Some professionally recognized and validated indicators show that investment in these resources has declined.

Thus, early and responsible financial investment in the nation’s health care infrastructure can mitigate this trend, enhance safety and improve performance, which eventually will allow the country to allocate more resources to direct patient care.

In addition, now more than ever, health care organizations need competent, motivated professionals to maintain and operate health care facilities.

Don D. King, CHFM, BEP, president, Donald King Consulting; Chad Beebe, AIA, FASHE, deputy executive director, ASHE; Joan Suchomel, AIA, ACHA, EDAC, senior vice president, Cannon Design; Peter Bardwell, FAIA, FACHA, principal, BARDWELL+associates LLC; Vincent Della Donna, AIA, ACHA, principal, Healthcare Architect; and Lisa Walt, Ph.D., senior analyst, advocacy, ASHE