The reality of designing simulation centers

The Johns Hopkins Medicine Simulation Center, Baltimore, is located in renovated space on the seventh floor of the Johns Hopkins health system’s former children’s hospital and includes simulated patient rooms, labor and delivery rooms, operating rooms and trauma/intensive care rooms.

The first time Stephanie Sudikoff, M.D., performed a breathing tube insertion, it was on a sick child. “It was terrifying,” she says.

As director of simulation at the Yale New Haven Health System’s SYN:APSE Center for Learning, Transformation and Innovation, Sudikoff is working to advance a model of clinical training that allows medical professionals to practice simulated health care scenarios before carrying them out in the real world, on actual patients. She also is associate clinical professor of pediatrics and pediatric critical care at Yale Medical School, New Haven, Conn.

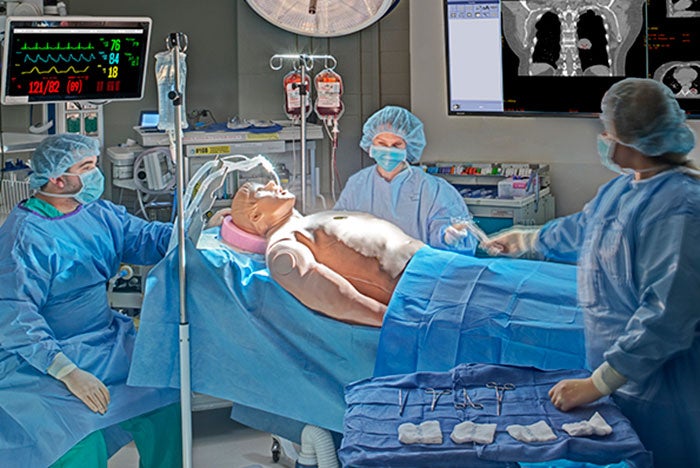

Medical simulation enables individual practitioners, medical teams and family caregivers to learn skills and techniques in safe environments that are similar in design to those in which they’ll deliver care.

Practicing under realistic conditions and having the opportunity to review and reflect on the experience aids learning and helps people to develop safer processes, equipment and environments of care. To gain the greatest value from this type of training, hospitals and health systems are building medical simulation centers in or adjacent to hospital facilities, so busy health professionals can access them easily.

Safe environment

The SYN:APSE [Simulation at Yale New Haven: Advancing Patient Safety and Education] Center is located directly across the street from Yale New Haven (Conn.) Hospital. The 8,000-square-foot center features a simulated hospital suite with medical-surgical, critical care, labor and delivery and neonatal intensive care rooms, a supply alcove and a multipurpose room for creating a variety of simulated environments like trauma, surgery and post-anesthesia care. Each of these spaces is equipped with advanced patient simulators and audiovisual equipment for recording simulation activities, and is operated by an individual control room. In addition, the center has a multifunction classroom, a skills lab, debriefing rooms, collaborative work space for SYN:APSE staff and a centralized storage area.

To help make training exercises feel real to participants, the clinical spaces are built to the same design standards as their counterparts at Yale New Haven Health System hospitals, “down to the paint color,” says Sudikoff. The flexible multipurpose room allows

SYN:APSE staff to adapt the space for different scenarios. The center’s services include education and training, professional evaluation and assessment, facility design and testing, environmental workflow analysis, systems integration and device testing.

At the SYN:APSE [Simulation at Yale New Haven: Advancing Patient Safety and Education] Center, clinical spaces are built to the same design standards as their counterparts at Yale New Haven Health System hospitals, down to the paint color.

“We work hard to create an environment where it’s safe to make mistakes, to reflect and to think about ways to prevent mistakes from happening when you’re caring for people,” says Sudikoff. The simulation center gives people the opportunity to train with the teams with whom they’ll work and on equipment they’ll be using. “Every day, some new piece of equipment is being deployed,” Sudikoff says. Learning to use a device safely before exposing it to a patient is valuable for everyone, from first-year residents to seasoned physicians, she notes. Equipment testing also can help supply chain teams compare and evaluate products. “The benefits run the gamut,” says Sudikoff.

At Boston Children’s Hospital, every space in the hospital simulation center is designed to serve multiple functions, to make the most of available square footage. Boston Children’s Simulator Program (SIMPeds) has a reception area that can also serve as hospital admissions in a medical simulation scenario, three simulation rooms and two collaboration rooms. By swapping out equipment and furnishings, simulation Room 1 can be made to resemble an outpatient clinic or a child’s home bedroom; simulation Room 2, a double trauma room, intensive care room or skills training laboratory; and simulation Room 3, an operating suite (which can be cooled for simulated cardiac surgery), a med-surg patient room or a post-anesthesia care area. Scenarios for activities like patient transport can be run across multiple rooms.

The smaller of the center’s two collaboration rooms can hold up to eight people; it is equipped for videoconferencing and device sharing and can be opened to include an adjacent simulation room. The larger collaboration room, covering 600 square feet, has panoramic views of the Boston skyline and can be divided into two separate spaces. This room, too, provides videoconferencing and device-sharing capabilities.

Boston Children’s Simulator Program (SIMPeds) has a reception area that can also serve as hospital admissions in a medical simulation scenario

State-of-the-art audiovisual equipment is installed throughout the SIMPeds center for recording simulations. Covered troughs in the flooring of the simulation rooms hide tubing for imitation blood and other fluids that are used to increase the realism of training scenarios. Melissa Burke, director of SIMPeds strategy and business development, says it was important to Boston Children’s to do everything possible in the design to help learners “suspend their disbelief that they are working on a real patient.”

In addition to the simulation and collaboration rooms, SIMPeds includes an inventor space and engineering core. The inventor space is a rapid-prototyping center for medical innovations. The engineering core provides labs for the development of whole-body mannequins and skills trainers that focus on a particular body part, as well as high-fidelity, 3-D-printed, patient-specific anatomic models for surgical practice. With these models, “surgeons can do the surgery before they do the surgery,” says Burke. “Previously, they had one chance, when the child was on the operating table.” Given the rarity and severity of many conditions treated at Boston Children’s, the opportunity to perform pre-surgical planning on an exact replica of the patient is highly valuable in reducing operating room time and improving outcomes, she says.

The Simulation Studio at the Connecticut Institute for Primary Care Innovation, Hartford, is an open, high-bay area where environments can be mocked up for training, research and development purposes.

Team building

The Connecticut Institute for Primary Care Innovation (CIPCI), a collaborative enterprise between Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center and the University of Connecticut School of Medicine, both in Hartford, was designed to provide a platform for team building that includes open discussion zones, technologically advanced conference spaces and simulation workshops. CIPCI’s Simulation Studio is an open, high-bay area where environments can be mocked up for training, research and development purposes. Depending on the size of the simulated environment and the number of people involved, participants can review a scenario in the simulation studio itself or an adjacent conference room. The studio’s interactive, dynamic design provides room for interdisciplinary training, says David D. Neal, AIA, ACHA, health care principal with The S/L/A/M Collaborative, Glastonbury, Conn.

The Johns Hopkins Medicine Simulation Center, Baltimore, is located in renovated space on the seventh floor of the Johns Hopkins health system’s former children’s hospital. The center includes simulated patient rooms, labor and delivery rooms, operating rooms and trauma/intensive care rooms, a “just-in-time” lab where medical professionals can practice skills as needed, and conference space. The simulation rooms have the square footage and technology necessary to accommodate debriefings of scenario participants. Audiovisual equipment is integrated into the corridors to allow the entire center to be used for simulations. Data and video collection software installed in the control rooms enable staff to control simulated systems from a central point, to create more realistic emergency scenarios. “Simulation doesn’t occur in just one room, but across the whole platform,” says Neal.

Critical access

The Davis Global Center, under construction on the campus of the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), Omaha, is a 192,000-square-foot clinical simulation facility expected to open next year that will serve as headquarters for the Interprofessional Experiential Center for Enduring Learning (iEXCEL). Each level will be dedicated to a different aspect of medical simulation.

The Davis Global Center, under construction on the campus of the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, is a 192,000-square-foot clinical simulation facility in which each level will be dedicated to a different aspect of medical simulation.

The lower level will feature a home care setting, with a bedroom and bathroom for rehearsing community care scenarios, as well as a simulated ambulance bay for practicing patient transportation and the transfer of patients from emergency medical services to a hospital.

The ground level will house a National Center for Health Security and Biopreparedness, with quarantine facilities and specialized labs for training federal health care professionals in caring for patients with highly infectious diseases.

Level 1 will provide virtual and augmented reality technology, including a 130-seat holographic theater; a 280-degree curved screen for showing 2-D and 3-D images (individually or simultaneously), with multiple-window capabilities that allow groups to collaborate on a 132M-pixel display; and a 3-D laser-immersive environment designed to help clinicians and researchers develop new treatment modalities.

Level 2 will focus on interprofessional simulation, with simulated acute care and critical care units, plus spaces for session preparation, review and discussion and skill-specific learning. Level 3 will provide a surgical skills suite with 20 simulated operating room bays and a command center to record and broadcast sessions locally or globally, a simulated hybrid operating and interventional suite and procedural surgical skills labs.

The site for the Davis Global Center was chosen for its proximity to UNMC colleges and Nebraska Medicine hospitals and clinics, to make the facility accessible to students and practicing health care professionals. “There’s no question, easy access is really critical,” says Pamela Boyers, associate vice chancellor for clinical simulation at UNMC. “Hospital staff are busy, and they become anxious when they’re away from their patients for [too] long.”

Ben Stobbe, R.N., executive director of clinical simulation integration for iEXCEL, says the program is in tune with Nebraska Medicine hospital safety committees, to develop scenarios for training health care teams on potential safety issues. Simulated care environments help to identify faulty processes by testing workflow rather than simply training individual caregivers. “It’s not just about a skill set,” says Stobbe.

‘Ultimate benefit’

The Val G. Hemming Simulation Center at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USU), Bethesda, Md., has a clinical skills lab, surgical and procedural skills lab, computer lab and virtual medical environments lab. Joseph O. Lopreiato, M.D., MPH, CHSE, professor of pediatrics and USU associate dean for simulation education, says Hemming center staff work closely with staff from the simulation center at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, which is located on the same military base as USU, to provide a comprehensive range of training scenarios for medical students, hospital residents and staff. Exposing learners to simulated health care environments early in their training helps in their transition to the hospital, while the hospital simulation center extends their training, Lopreiato says.

Medical simulation is safer than the traditional training model of “see one, do one, train one,” where “patients are your training apparatus,” says Harry Robinson, national program manager for the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) Simulation Learning, Education and Research Network (SimLEARN). With simulation training, he says, “you never put a patient at risk.” SimLEARN supports a network of VA clinics in providing medical simulation training at their facilities.

The program is headquartered at the Veterans Health Administration’s SimLEARN National Simulation Center, a 51,000-square-foot facility on the Orlando (Fla.) VA Medical Center campus. The building features simulated hospital, clinic, behavioral health and community living spaces; multiple debrief rooms; a computer room; a broadcast/video suite; and multipurpose classrooms with reconfigurable walls. An environment that allows for interprofessional training helps people to develop the communication skills necessary to provide medical care, says Robinson.

He adds that medical simulation is an efficient way to train, because it doesn’t depend on having a patient present with symptoms at a particular time or place. With simulation training, “you can practice the exact process you just discussed,” he says. Scenarios can be repeated and refined any number of ways, enabling people to master techniques for which they may have few opportunities to practice in an actual clinic or hospital setting.

“The ultimate benefit to patients is that they get better health care. They get providers who are better trained,” Robinson says.

Amy Eagle is a freelance journalist based in Homewood, Ill., who specializes in health care-related topics She is a regular contributor to Health Facilities Management.