Designing hospitals for the millennial generation

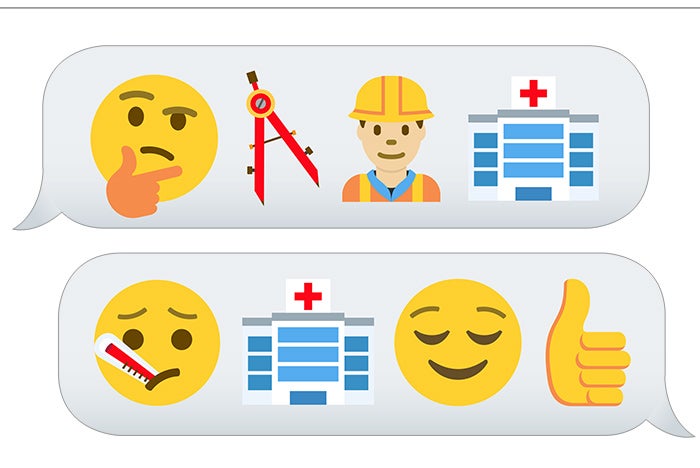

The millennial generation is all grown up. The youngest millennials are heading into their 20s, the oldest are in their mid-30s. Individuals in this demographic, which has overtaken the baby boomers as the largest age cohort in the U.S., not only are making decisions about their own health care, they are driving care decisions for their children and parents.

To serve the needs of this large and influential segment of the health care market, providers and designers are looking to create facilities built for a new generation.

Frank Zilm, D. Arch., FAIA, FACHA, Chester Dean Director of the Institute for Health+Wellness Design at the University of Kansas, Lawrence, says that to address the needs of a new patient population, health care and design professionals should begin by researching places the people in question tend to congregate.

“What’s the kind of environment they’re comfortable in, and to what degree can we respond to that in terms of a health care environment?” he asks. “I would want to know more about the behavioral patterns and typical situations of the population, to see to what degree we can reflect or support that in the physical environment we’re trying to create in the health care world.”

Enhanced experience

Dallas-based architecture firm HKS Inc. and JE Dunn Construction Group, Kansas City, Mo., explored similar questions for their report, “Clinic 20XX: Designing for an Ever-Changing Present.” The report is based on research conducted by HKS’ nonprofit research unit CADRE in an effort to determine principles for designing clinics that can adapt to rapidly changing needs. As part of the study, an independent, third-party survey firm polled people from the nation’s two largest age cohorts — baby boomers and millennials — about their perceptions of health care.

Individuals surveyed had visited at least one clinic for the first time in the past six months.

Upali Nanda, Ph.D., associate AIA, EDAC, associate principal and director of research, HKS, says one of the most surprising findings from the survey is that a large majority of millennials said they view themselves more as patients needing care than as consumers buying health services. “We hadn’t expected that,” she says. “We thought millennials would be more on the consumer side.” Eighty-five percent of the millennial group described themselves as patients rather than consumers, though younger millennials tended more toward a consumer viewpoint of health care — an important trend, given this demographic’s penchant for researching and rating experiences [see sidebar, Page 20].

Nanda says another surprising survey finding was that even in this age of information, a majority of millennials said they trust people more than information, such as material they read or view online; 55 percent of both millennials and baby boomers indicated they put their faith primarily in other people. “This makes sense given the rise of social media, where online information is mediated through our social circles,” notes Nanda.

Sixty-two percent of millennials said that in addition to having their health care needs met, they want to have a good experience as patients; just 52 percent of baby boomers said a good experience is as important as addressing their health care needs. And in a result that seems unsurprising, a majority of millennials — 54 percent — described their phones as being lifelines, as opposed to simply tools for communication, and that they would like to use them to access health care services.

When asked to rate the factors that made them select their clinic, millennials’ top three answers were: coverage under their health plan, overall cleanliness and hygiene, and on-site diagnostics.

The survey also looked at factors related to patient satisfaction, revealing millennials to be slightly more difficult to satisfy than baby boomers and slightly less likely to return to a clinic. The top predictors for a return visit were found to include general satisfaction with the clinic, including wait times and service quality; follow-up care; and Wi-Fi connectivity.

A prototype clinic design developed by HKS Inc. demonstrates a waiting concept similar to Apple Inc.’s Genius Bar.

In rating a list of attributes that would make a clinic more appealing for a return visit, millennials ranked cleanliness and hygiene, walk-in appointments with less than a 30-minute wait and same-day appointments as their three highest priorities.

Unlike baby boomers, who concentrated on these same top three attributes, millennials went on to give every item listed a fairly high rating. These included a quiet environment; 24/7 access; online registration; daylight and views; virtual or video access to a remote clinician; fitness, wellness and retail amenities; mobile apps for making appointments and tracking health information; and a spalike environment.

“Millennials just want more,” Nanda says. “They have higher standards and make decisions critically. So, we give them clean, we give them efficient and we give them an enhanced experience that exceeds expectation. And to do so, we have to understand them better, and raise the bar higher for our own industry.”

Greater connectivity

The health care experience must now extend across a variety of settings. Ryan Hullinger, AIA, partner in the Columbus, Ohio, office of architecture firm NBBJ, says, “We used to be extremely focused on the hospital as the place where care is provided, and now care is administered in so many different environments.” Today, these include hospitals; ambulatory care centers; retail outlets like drugstores; workplace wellness programs; and wearable health and fitness monitoring devices.

“With this generation, there’s definitely an expectation that health care is going to happen in multiple environments. That’s a very important consideration for us, the end of the primacy of the hospital,” Hullinger says. “But even within the design of the hospital, it’s interesting how you can calibrate an inpatient room or exam room for the changing needs of millennials,” he adds.

As demonstrated by the Clinic 20XX report, one of these needs is connectivity to both technology and other people.

Patients today expect technology to be seamlessly integrated into the health care experience, so they can participate more fully in their care, says Kerianne Graham, RA, AIA, associate, health care architect, NBBJ’s New York City office. Online registration, digital check-in kiosks and computer displays that allow patients and caregivers to review and discuss health information together are important to designing a positive patient experience, she says.

“Think of facilities as having both a cloud print and a footprint,” says Nanda. “Technology is integrated into the architecture, into the design, so that it’s one cohesive solution for enhanced experience.” Instead of constructing a building and adding technology to it, designers should plan for what’s going to happen in both the digital and the physical space, she says.

“Structurally, technology needs to be nimble. Everything has to be connected. And by connected, we mean physical connectivity for people within that space, and digital connectivity within a system,” says Nanda.

Designs that provide a sense of place along the continuum of care are important in making patients feel connected, too. Regardless of whether people are at an anchor hospital, community clinic or interfacing with their health system via a device at home, they should recognize where they are and who is taking care of them. “Loyalty is at a premium, people have choices, and they need to feel wherever they step in [to a health system], they’re home,” Nanda says.

Millennials also value personal connections. “The idea of being in a community, being networked, either virtually or physically, with family and with friends” is important to the millennial demographic, says Hullinger. Designs that enable families to be together during a hospital stay help to meet this need.

NBBJ’s design of Seattle Children’s Bellevue (Wash.) Clinic and Surgery Center, for example, features an optimized surgical flow with induction rooms connected to the operating rooms, so that parents can stay with their children as long as possible prior to surgery — even as anesthesia is administered. Large waiting areas aren’t needed at the facility, thanks to the efficient, streamlined design.

NBBJ designers have developed a patient room concept that can be reconfigured throughout the day to provide furnishings for work, sleep and family dining with technology support. Click the image above to see other configurations

Compact concept

NBBJ designers have developed a patient room concept that combines these ideas of virtual and personal connectivity with the efficiency and flexibility of microapartment design. The room’s footwall can be reconfigured throughout the day to provide furnishings for work, sleep and family dining. Technology in the room supports caregiver consultations (in person and virtual), as well as patient education, entertainment and online networking.

The concept room was developed as part of an organizationwide initiative to transform health care spaces to better care for specific generational profiles. Hullinger says that in researching designs and ideas that appeal to millennials, the design team hit on the idea of the microapartment. “Not because we always seek to make a patient room look like home — I think that’s a cliché we moved past long ago. But this was one particular instance where there were some ideas about the way that millennials were living that could be transcribed onto the space of the patient room in an interesting way,” he explains.

According to Hullinger, the team found that the concepts of flexibility and transformability resonate with millennial culture, which is focused on economy, doing more with less and being able to transform a space creatively. “We thought there would be a sensibility to this [design] that would resonate with that demographic,” he says.

The economy of the design and the value it places on family relationships are intended to appeal to baby boomers, as well. “What’s at the heart of this patient room is the idea that it accommodates and supports those relationships much better than a conventional patient room,” Hullinger says.

The concept room has the bed clearances of an intensive care room. The reconfigurable design converts the 20 to 30 percent of floor area that often goes unused in a universal room into a zone of amenities along the footwall.

The room’s most-compact configuration, which maintains the intensive care clearances, features a built-in couch for comfortable seating, with storage underneath. This configuration provides ample space for consultations among the care team, including the patient and family. A large video screen on the wall can be used for telemedicine or to display patient health information.

“You can set the source for clinical content: patient records, consults, videoconferencing with physicians around the world. But you could switch the source to entertainment content. And I think that’s a really important driver for millennials as well — being able to adapt the room for their own entertainment purposes,” Hullinger says.

When the intensive care clearances aren’t needed, a double bed can be pulled out of the wall to provide a good night’s sleep for family members. With the bed stowed away, a spacious desktop can fold down to provide work space. At mealtimes, a dining table that seats as many as four adults can accommodate family and friends.

Graham says, “When we were looking at the microapartment, we saw it’s not one thing, it’s many things throughout the day. So, as we were thinking about the functions of the patient room, that’s what started the dialogue about being able to support the family as a member of the care team.” While family-centered care is a term that’s been around for years, physical space doesn’t always support the family aspect of care as much as it could, she adds.

Providing for family needs in the design of the patient rooms allows nursing staff to concentrate on highly skilled caregiving, rather than spending time doing small tasks family members can accomplish or spending energy de-escalating situations with unhappy families, notes Hullinger.

To keep things simple for visitors and staff, the footwall is designed to be reconfigured easily. “It’s one hand to take it down and put it up,” Graham explains. “It’s not something that would be limiting, so you wouldn’t necessarily have to have the staff do it.” An ultraviolet light disinfection system can be built into the footwall to clean surfaces between uses. And since the room is built on a universal module, it can convert from being family-oriented to acute care-oriented “in a matter of minutes, instead of with a remodel,” says Hullinger.

Historically, patient rooms were designed around ergonomics and operational efficiency, he notes. As the integration of family began to inform room designs, the family experience was often shoehorned into rooms that were still fundamentally driven by staff experience and efficiency. “What we’re trying to do here is break that paradigm, so that you have these two things working together in a more integrated way,” he says.

Withstanding change

Trying to determine what the clinical future looks like is a difficult question to ask of facilities, says Nanda, because demographics, technology, care protocols and policy change so fast, “and facilities have to stay in place and withstand the change. It’s one reason we talk about Clinic 20XX, instead of 2020 or 2040. We need to be change-ready and future-proof.”

By studying the preferences of each new generation, health care designers can develop ideas for facilities that support the needs of today’s patients while planning ahead for those of tomorrow. As millennials emerge as the nation’s next big demographic wave, their ideas about the health care experience, efficiency and connectivity are leading facility design into the future.

Amy Eagle, a freelance writer based in Homewood, Ill., specializes in health care-related topics. She is a regular contributor to Health Facilities Management.