Safety zone

The past 10 years have seen enormous effort and emphasis on designing better patient bedrooms — single patient rooms that contribute to healing and beneficial outcomes, patient safety and family inclusion. For the most part, however, one primary component of the patient bedroom — the bathroom — remains an area that disappoints and perhaps endangers patients, challenges designers and frustrates owners.

The past 10 years have seen enormous effort and emphasis on designing better patient bedrooms — single patient rooms that contribute to healing and beneficial outcomes, patient safety and family inclusion. For the most part, however, one primary component of the patient bedroom — the bathroom — remains an area that disappoints and perhaps endangers patients, challenges designers and frustrates owners.

A recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study suggests that the bathroom is the most dangerous room in the house. There is no reason to believe that patient bathrooms in hospitals are much safer, even with grab bars, call alarms and 24-hour nursing. In fact, many elements introduced into the design of the patient bathroom to reduce or resolve one problem may well contribute to another.

Some key design challenges involve optimizing patient safety in both fall and infection prevention while maintaining an accessible and aesthetically pleasing environment for the patient, family and visitors. All this must be accomplished while trying to minimize the size and cost of the bathroom. Add the conflicting goals of a universal bathroom design that will serve all medical-surgical patients and meet Americans with Disabilities Act Accessibility Guidelines (ADAAG) and the needs of an increasing bariatric patient population and it becomes apparent that patient bathroom design requires a series of trade-offs.

Location, location, location

Under the premise that every patient bedroom has a full bathroom, there are only a few locations for the bathroom: inboard along the corridor wall, or outboard along the exterior wall; and at either the headwall or the footwall. Another possibility nests toilets back to back between bedrooms. Occasionally, to augment space within the module, the bathroom is "popped out" beyond the edge of the exterior wall making it a statement in the building's massing or inward toward the corridor, often creating a vestibule at the corridor.

Eliminating or reducing patient falls is often a factor in bathroom location. One design response has been to locate the bathroom along the headwall so unassisted patients have something to hold onto as they make their way to the bathroom. There is no evidence yet that this layout has reduced patient falls and there is some concern that it may increase risk inadvertently by encouraging patients to think they can manage to get to the bathroom by themselves.

In many instances the decision to locate the bathroom along the footwall is made to improve visibility into the patient bedroom from the corridor. However, there has been anecdotal reporting that this more remote location makes it more difficult for nursing staff to hear patients when they are in the bathroom, limiting their ability to offer assistance.

Bigger bathrooms

It is not uncommon to find patient bathrooms from the 1970s that measure less than 20 net square feet (nsf) and include only a toilet and sink. Today's near-universal inclusion of a shower in the acute care bathroom increases bathroom size to 30 nsf, with the requirement for ADAAG typically adding 12 nsf or more. Other factors that also have significant importance in patient bathroom size are access and door size, safe patient handling and bariatric patient populations, as well as a strong desire for uniformity by design owners and clinical teams.

The ADAAG requirement that 10 percent of all patient rooms have ADAAG-compliant bathrooms has been both beneficial and challenging. These larger bathrooms generally have proven to be more usable for nursing staff in assisting patients; the problem has been that the 10 percent inclusion has resulted in too few accessible rooms and a difficulty in matching ADAAG rooms with the patients who most need them.

Safe patient handling suggestions include a minimum of 24 inches between the patient toilet and the bathroom wall (as opposed to 18 inches from the centerline of the toilet fixture to the wall for the ADAAG), with 42 inches on the opposite side of the toilet. Bariatric requirements are even greater.

Historically, the Facility Guidelines Institute's Guidelines for Design and Construction of Health Care Facilities have been silent about size requirements in patient bathrooms. The 2010 Guidelines do not include specific dimensions or size requirements, but its new provision for patient lifts, which states that "patient shower rooms shall be designated to allow entry of portable/mobile mechanical lifts and shower gurney devices," has an inherent impact on space.

Safe accessibility

The type and size of the patient bathroom door impacts the ease of access for both patient and caregiver and has been implicated in patient falls.

In determining appropriate access, there may be a trade-off between access into the toilet, door collisions and clearances in the bedroom. Doors to patient bedrooms must swing out or have emergency rescue hardware to prevent fallen patients from inadvertently barricading themselves within the bathroom.

Door size affects bathroom size because there has to be a wall long enough to adequately accommodate the door opening. Different options pose their own trade-offs:

• A 36-inch door is too small to allow a patient to be assisted into the bathroom, and a patient may fall during the solo transition.

• A 39-inch door may be wide enough for a large wheelchair, but doors larger than 48 inches often are too heavy for patients to maneuver easily.

• A double-leaf door will improve access for an assisted patient but may affect the size of the bathroom and bedroom, with cost and maintenance implications for the added leaf and hardware.

• A large sliding door may minimize encroachment on the bedroom and the effort needed for opening, but will require a partition at least the width of the slider when the door is open. Sliding doors also may be risky for patients who reach for them to steady themselves, and may limit handrail and grab bar placement. Finally, a sliding door requires special hardware that maintenance staff may feel uncomfortable servicing.

|

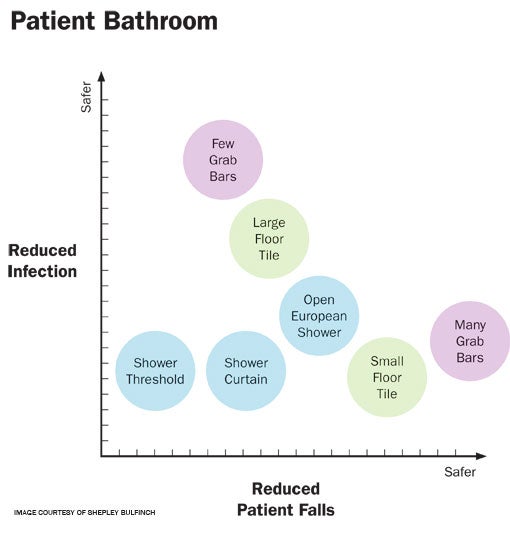

| Rather than creating an optimal patient environment, decisions made in patient bathroom design may require striking a balance between reducing infection and reducing patient falls. |

The fixture triangle

The relationship of the fixture triangle — toilet, sink and shower — may define a bathroom's success. For many designers, the first imperative has been to locate the toilet close to the door, as the primary destination of patients most of the time, perhaps with some urgency.

Locating the toilet adjacent to the sink may allow a weak patient to access the sink and mirror while sitting, or to lean on the sink or vanity for stability. Separating sink and toilet requires that the patient cross the bathroom, and may increase the likelihood of falling for lack of a steady handhold. In many instances, locating the shower in the corner farthest from the door may help control water but may also mean the separation of toilet and sink.

Construction considerations that play a role in the configuration of plumbing fixtures include grab bar requirements, chases, structural supports and drain locations.

Lighting also can make or break any design. Given the relatively high incidence of toilet-related nighttime falls, making sure that patients can see their way to and within the bathroom is important. Outboard patient bathrooms increasingly include windows, often as part of exterior fenestration design, providing access to translucent daylight.

Falls and water hazards

There is evidence that bathroom fall injuries likely will be more severe than bedroom falls, presumably because of the bathroom's hard and immovable surfaces and fixtures. Unfortunately, there is no ideal bathroom size small enough to always provide a grab bar or safe surface for a patient to hold onto, but large enough so that they make it to the floor without meeting a plumbing fixture if they do fall.

A major contributor to falls is the slippery surface created by water. Efforts to control water have led to shower design solutions that replace a slipping hazard with a tripping risk, such as when a lip or shower enclosure is installed; or an infection risk, such as with the use of small, difficult-to-clean tiles.

The location of the toilet paper dispenser also can contribute to bathroom falls. The size of dispensers, which are growing larger to reduce the number of changes, means that they are now often so low and forward from the toilet that patients must lean forward to reach them and may lose their balance.

While one common response in trying to design a safer bathroom has been to add grab bars throughout, it is not clear whether doing so contributes to patient safety or to patient risk. One issue is grab bar placement. The ADAAG prescribes locations around the patient toilet which, while they may be suitable for a population with upper body strength, may be less effective for the frail, sick and elderly. In response, supplemental grab bars frequently are added, and it isn't uncommon to find four or more near the toilet. But how well are these multiple grab bars likely to be cleaned? Studies have pointed to grab bars as being among the dirtiest components of a patient bathroom.

Infection risks

The patient bathroom is one area where good design can help prevent health care-associated infections (HAIs) and their human and financial costs. Each bathroom surface must be durable and easy to clean and maintain. Features such as door frames, casework and finish transitions must be carefully detailed to avoid hard-to-clean crevices and joints.

Of special concern in infection prevention are the materials that surround the patient toilet. Eliminating spores calls for solid surface flooring material and the elimination of joints and crevices. Here, reducing slipping risk runs headlong into infection control.

While smaller floor tiles in the shower area may be easier to manipulate with sloping floor angles and the increased grouting may reduce slippage, inadequate grouting may provide places for dirt to cling, making cleaning difficult and time-consuming. Likewise, an infection control response — using different flooring materials for the toilet and shower — may pose an aesthetic challenge.

Antimicrobial products quickly are becoming standard in patient bathroom design, although the efficacy and cost effectiveness can be difficult to demonstrate. A number of metal products have been considered over the years and there is considerable interest today in copper alloy products. Another product is tile that incorporates titanium dioxide, a photo catalyst that kills bacteria and fungus. Solid surface material often is used because it is easy to clean and does not promote bacterial growth.

Shower safety options

Because water control is linked to patient bathroom safety, the shower is a major concern. Although showers typically are included in the patient bathroom, the percentage and types of patients and family members who shower remain open questions. However, failing to include showers in the patient bathroom may limit future flexibility to accommodate changes in acuity or assignment.

The European shower concept, which treats the entire bathroom as the shower, may be popular largely because it provides enough space in the bathroom for safe patient handling and nursing assistance, perhaps at the expense of an optimally functional shower.

In general, there are three principal shower options:

• Small enclosed showers improve patient privacy and limit water penetration into the bathroom, keeping the floor dry and reducing slip risk. However, this configuration may limit caregivers' ability to assist patients and may result in shower areas that are not large enough for many patients.

• Larger showers provide extra space for assistance and may meet ADAAG requirements. A curved shower rod adds room for patients without requiring additional floor area. Positioning the shower at a corner limits water penetration into the room, keeping the floor dry and reducing patient slip risk, but may mean separating the toilet and sink, creating a potential fall risk. This is particularly true if the angled floor of the shower zone makes walking treacherous for patients.

• The European model, in which the shower is essentially a corner of the room, provides the maximum ability to assist the showering patient, but makes water control more difficult and may increase the slipping risk. While this option can most easily accommodate the bariatric patient population, it presents an infection control issue, as room surfaces often become wet and stay wet. A variation with a threshold at the bathroom door minimizes water penetration into the bedroom, but may introduce another tripping hazard and make patient movement with an IV pole difficult.

Water control depends on the location of the head and controls relative to the shower access and opening. In a small enclosure, there is both a smaller opening and a basin to catch and contain water, although this also may limit accessibility and create a tripping hazard. When the shower is open to the room, the drain location is critical for water control.

Other safety features in the shower may include:

- inclusion of a shower seat to provide stability to those unsure of their footing;

- removal of shower thresholds for easy access and to eliminate a tripping hazard;

- conveniently located grab bars.

Shower curtains that are either ethylene vinyl acetate or cloth allow privacy and splash control and can be moved out of the way quickly to allow caregiver access. However, if not cleaned or disposed of appropriately, they may be a source of potential patient infection.

Assessing the trade-offs

Treating the patient bathroom as a design exercise with its own programmatic requirements and wisely assessing the many trade-offs involved helps to ensure that it lives up to the aspirations of all involved.

Jennifer Aliber, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP, is a principal with the national architecture firm of Shepley Bulfinch, where she is a leader of the firm's health care practice. She can be reached at JAliber@shepleybulfinch.com.

| Sidebar - Bathroom design + the visually impaired |

| While the Americans with Disabilities Act standards for accessible design strive to provide persons with disabilities the same ease of use and access in a building as persons without disabilities, they do not take into account the needs of the visually impaired. Unlike patients who are blind, those with low vision have limited sight and must deal with difficulties that include lack of depth perception, clarity and the ability to distinguish foreground and background. To accommodate these patients and meet requirements related to mobility, the toilet rooms of the Vision Rehabilitation Service at Massachusetts Eye and Ear in Boston had to address these challenges. It was clear from the outset of the project that the existing monochromatic toilet rooms with same-color walls and fixtures were not visually distinguishable and that setting design guidelines and testing them would be central to the design. Consequently, the Institute established a model facilities committee of patients, clinicians and staff to establish design criteria from detailed information about users' needs and then to validate the design schemes by testing them. Through this exercise, designers determined that the ideal contrast ratio for the visually impaired is 70 percent. The toilet room design, now standardized institutionally, has a "wet wall" rendered with a dark solid-surface panel to contrast with the white plumbing fixture. A dark band in the flooring beneath the fixtures further distinguishes them. Indirect lighting was used to minimize glare. The new toilet rooms have received high praise from users. Most evocative was the remark of one patient to a senior clinician, "This is like being given my sight back." By Cindy Lee, AIA, LEED AP, an architect with Shepley Bulfinch. |

| Sidebar - Infection control + the cleaning regimen |

| Proper cleaning and disinfection of hospital spaces has never been more critical than it is today, and few locations within a hospital harbor more potentially serious infectious organisms than the patient bathroom, where cleaning staff and others routinely are likely to encounter the highest concentration of bio load. The design of patient bathrooms must factor in the ability for these spaces to be thoroughly disinfected and sanitized as well as being functional. As hospitals and designers create new space to address the ever-changing clinical and technological environment that is health care today, an opportunity is created to reinforce this cultural shift in cleaning and infection control throughout the hospital and to emphasize and introduce new techniques and products to enhance patient, staff and visitor safety. Staff members in environmental services, maintenance and other hospital departments are now as responsible for protecting the health of patients, visitors and fellow staff members from health care-associated infections as are physicians and nurses. Everyone who comes into contact with patients and the patient room must be attentive to infection control practices relative to these spaces, particularly the patient bathroom and toilet area. Cleaning agents that once were the standard in the industry now are often ineffective against resistive strains of many of these organisms and simply spraying and wiping with a disinfectant is no longer adequate. Recent studies even suggest that introducing hydrogen peroxide vapor and ultraviolet light processes to enhance traditional cleaning methods may be warranted. New hospital spaces impact the culture of a hospital in many ways. As these spaces are created and new pathogenic threats identified, additional cleaning and disinfection measures will need to be identified and opportunities will be created to apply these new measures. The patient bathroom is a prime example of such an opportunity. By Ray Gerbi, a health care facilities consultant and former vice president of facilities for Concord (N.H.) Hospital. |