Hospitals lay battle plan to fight aggressive pathogens

A CDC-funded study at nine hospitals recently found that using ultraviolet light disinfection with traditional cleaning chemicals reduced health care-associated infections.

In 2012, South Seminole Hospital in Orlando, Fla., began a broad-based initiative to improve patient safety and reduce health care-associated infections at the 200-bed facility. All links in the infection prevention chain were examined as part of a systemwide movement within Orlando Health, a seven-hospital system. The efforts produced impressive results.

“After a year, we had solid data from South Seminole Hospital,” notes Tom Kelley, M.D., chief of quality and clinical transformation for Orlando Health. “We reduced our hospital-acquired Clostridium difficile infection [CDI] rate by 47 percent even though community-acquired C. difficile rose by 7 percent during this time.”

You may also like |

| Assessing infection control practices |

| Environmental services technologies |

| ES and C. difficile prevention |

|

|

The facility also reduced hospital-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) by 30 percent and hospital-acquired vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) by 50 percent, Kelley notes.

Bundle up

An evolving bundle of interventions implemented by the clinical and quality staff, environmental services (ES) personnel, infection preventionists and others led to the safety improvements. The measures included stepped-up efforts to monitor hand-hygiene compliance, including reporting and auditing findings by department, which led to greater peer accountability. Antibiotic stewardship became a deeper systemwide focus. Pulsed xenon ultraviolet light (UV) disinfection was added as a supplemental step to terminal cleaning in the intensive care unit, operating rooms and all contact isolation precaution rooms.

Other steps were taken in what was reminiscent of a previous multilevel effort that cut surgical-site infection rates by 30 percent throughout the Orlando Health system.

“What we’ve learned is there doesn’t seem to be a single magic bullet,” Kelley says.

Leading infection prevention organizations, patient safety groups, clinical and ES leaders and others have come to this conclusion as well. In June, leaders from these areas gathered at the White House to discuss implementing the National Strategy for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and to address recommendations from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.

The group covered such issues as:

• Misuse and overuse of antibiotics in health care and food production.

• Implementation of evidence-based infection control practices to prevent the spread of resistant pathogens.

• New technologies like whole genome sequencing to develop next-generation tools to strengthen human and animal health.

Together, the national plan’s five goals could cut by 50 percent the incidence of C. difficile compared with estimates from 2011 and carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE) infections acquired during hospitalization by 60 percent.

Additional resource

This downloadable infographic shows some of the risks of C. difficileand preventative measures that health facilities can take to prevent its spread.

The synergistic effect

To achieve goals like this, infection prevention experts believe there must be more comprehensive, carefully coordinated initiatives deployed across health care facilities and health systems. Likewise, more qualitative and quantitative research will be needed to demonstrate which infection prevention protocols and technologies definitively reduce HAIs.

For example, while Kelley is convinced that UV disinfection played a significant role in reducing HAIs in treated rooms, he says it’s impossible to quantify the number of infections that were prevented from this or any other single measure. He believes the combination of overall efforts produced a synergistic effect.

“We think it was the combination of using UV disinfection with increased attention among patients; better communication with staff and families on hand hygiene; antibiotic stewardship; careful use of proton pump inhibitors; bagging and labeling contaminated equipment [from rooms of infected patients before sterile processing]; and cordoning off rooms after being treated with UV disinfection to prevent recontamination that helped us to achieve these results,” Kelley says.

South Seminole Hospital and Orlando Health aren’t the only ones taking a fresh look at best practices to reduce HAIs and improve patient safety. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on Sept. 14 convened a panel of 30 clinical and academic experts, health care industry leaders, patient advocates and federal agencies to discuss the current literature regarding patient surface contamination, how infection transmission occurs from these surfaces and what facilities can do to improve surface cleanliness.

Key areas discussed included:

• Understanding transmission events related to room surfaces so that facilities know which surfaces are most likely to become contaminated, and can optimize cleaning and disinfection practices accordingly.

• Standardizing methods to measure cleanliness and the need for further studies to evaluate whether certain levels of cleanliness are associated with improved patient safety.

• Improving cleaning processes, including training and education of ES workers, methods for monitoring cleaning and disinfection, and structural challenges to the work of ES teams.

• Improving cleanliness by evaluating emerging interventions and technologies designed to aid cleaning and disinfection.

“One of the biggest issues discussed was the human factors that influence the ability of environmental services workers to do their jobs well,” says Sujan Reddy, M.D., guest researcher in the CDC’s division of health care quality promotion.

Overcoming human factors

Indeed, it is paramount to understand how to overcome human factors that can lead to inconsistent results in cleaning and disinfection practices, hand-hygiene compliance and other efforts to improve overall patient safety and outcomes. Hudson Garrett Jr., Ph.D., CHESP, industry liaison for the Association for the Healthcare Environment (AHE) board of directors, believes the need for greater collaboration among ES professionals, infection prevention leaders and others is vital to improving patient safety and removing barriers.

“As you look at the environment of care standards from the Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services requirements, if we don’t work together, there won’t be any truly sustainable improved outcomes,” Garrett says.

Additional resource

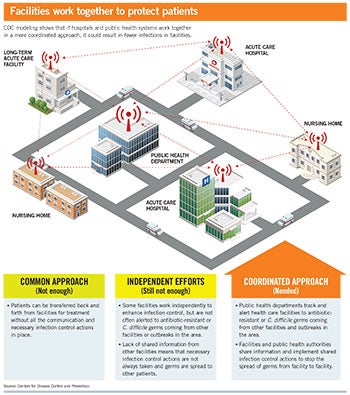

This downloadable infographic shows how a coordinated communication plan could result in fewer infections in facilities

Training on collaboration and teamwork historically have not received enough attention, Garrett believes. Likewise, he sees the issues of training and ensuring that ES teams have the resources they need as critical to achieving consistency in practice.

“I think the biggest and most important tool in this fight is the AHE’s Practice Guidance for Healthcare Environmental Cleaning, because it’s the only evidence-based publication that provides the methodology so you can make sure [cleaning and disinfection practices] are consistent every time,” Garrett says.

Even with consistent adherence to best cleaning and disinfection practices, many experts believe supplemental tools are needed to consistently safeguard patients and staff from today’s more virulent strains of multidrug-resistant organisms.

With increasing frequency, hospitals are turning to automated tools to monitor areas like cleaning thoroughness, hand-hygiene compliance and terminal room cleaning and disinfection. For example, Health Facilities Management’s 2015 Sustainability Survey found that one in four responding hospitals reported using UV light disinfection in some part of their facilities.

Yet, while many studies have documented the ability of UV light disinfection to kill antibiotic-resistant bacteria in hospitals, comprehensive independent studies across multiple facilities over time to document whether these systems reduce HAIs have been almost nonexistent, primarily due to lack of funding.

In October, however, the Duke University School of Medicine released partial results of what is believed to be the largest and most comprehensive independent study of UV disinfection technology in hospitals to date. The CDC-funded study found that using a combination of traditional cleaning chemicals (including quaternary ammonium and bleach) and UV light to clean patient rooms cut transmission of C. difficile, MRSA, VRE and Acinetobacter by 10 to 30 percent among patients who stayed in a room previously occupied by someone with a known positive culture or infection of a drug-resistant organism. This group of patients represented about 5 percent of more than 600,000 patients across the nine study hospitals in the Southeast.

Underscoring the significance of the highly controlled study, Deverick J. Anderson, M.D., an infectious disease specialist at Duke Medicine, noted when the findings were released: “Several groups have demonstrated that enhanced cleaning strategies, such as using portable UV machines, can kill these germs, but this is the first well-controlled study that shows these techniques can make a meaningful difference in patient outcomes.”

Cliff McDonald, M.D., senior adviser for science and integrity at the CDC’s division of health care quality promotion, cautions that the types of disease transmission points examined in this study represent perhaps 5 to 10 percent of all HAI transmission events nationally. Still, he says, the data indicate that using UV light to disinfect rooms is more effective than traditional cleaning methods and products alone. Another key point is that the facilities in the study consistently demonstrated success rates of 90 percent in hand-hygiene compliance and surface cleaning — rates few hospitals achieve consistently. Thus, even with high success rates in hand washing and traditional cleaning and disinfection methods, UV light helped to achieve higher disinfection levels.

Jim Davis, R.N., CIC, senior infection prevention analyst at ECRI Institute, says the Duke study will add clarity to what can be a confusing issue for hospitals. He says that while research demonstrates how technology can aid in surface disinfection, the results only can be achieved with consistently meticulous attention to manual cleaning processes.

“We have to caution people that they can’t let their regular cleaning practices lapse and rely on [technology] to catch what they’re missing. There has to be a coordinated process,” Davis says.

Katherine Velez, Ph.D., a scientist at Clorox Healthcare, which offers two UV disinfection light systems for disinfecting environmental surfaces, says research like that funded by the CDC and a recent Clorox-funded study at Penn Medicine’s Perelman School of Medicine showing that UV light cut C. difficile transmissions by 25 percent on cancer patient floors, help to demonstrate the technology’s value. She, too, adds that the technology is but one part of a comprehensive and multilevel approach to combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Bob Kehoe is a senior editor for Health Facilities Management.

For more information

The following resources were consulted for this article and offer valuable information regarding environmental cleaning and disinfection practices and technology, hand hygiene compliance guidelines and more.

• Practice Guidance for Healthcare Environmental Cleaning, 2nd Edition, provides evidence-based research, guidance and recommended practices that should be considered for inclusion in health care environmental services departments.

http://www.ahe.org/ahe/learn/tools_and_resources/publications.shtml

• National Action Plan for Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (March 2015) provides a roadmap to guide the nation in rising to this challenge.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/national_action_plan_for_combating_antibotic-resistant_bacteria.pdf

• Environmental Cleaning for the Prevention of Healthcare-Associated Infections (August 2015) from AHRQ summarizes the evidence base addressing environmental cleaning of high-touch surfaces in hospital rooms and highlights future research directions.

http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/ehc/products/592/2103/healthcare-infections-report-150810.pdf

• Joint Commission Hospital National Patient Safety Goal (effective Jan. 1, 2015) NPSG.07.01.01 describes how to comply with the current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and World Health Organization (WHO) hand hygiene guidelines.

http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2015_NPSG_HAP.pdf

• Joint Commission Hospital National Patient Safety Goal (effective Jan. 1, 2015) NPSG.07.03.01 describes how to Implement evidence-based practices to prevent health care–associated infections due to multidrug-resistant organisms in acute care hospitals.

http://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/2015_NPSG_HAP.pdf

• "Cleaning and Disinfecting Environmental Surfaces in Healthcare: Toward an Integrated Framework for Infection and Occupational Illness Prevention” (American Journal of Infection Control, March 2015) describes an integrated framework that was developed to guide more comprehensive efforts to minimize harmful cleaning and disinfection exposures without reducing the effectiveness of infection prevention.

http://www.ajicjournal.org/article/S0196-6553%2815%2900075-9/fulltext

• ECRI Institute: 2015 Top 10 Hospital C-Suite Watch List features a comprehensive overview of ultraviolet light disinfection units and hydrogen peroxide vapor equipment. A companion article discusses what to do before and after introducing one of these systems into a facility.

https://www.ecri.org/Resources/Whitepapers_and_reports/Top_Ten_C-Suite_Watch_List_2015.pdf