Surgical smoke codes and safety issues

An estimated 90% of all surgical procedures generate surgical smoke.

Image courtesy of AORN

Surgical smoke plume is a dangerous hazard that poses a health risk to operating room (OR) occupants during almost all surgical procedures. Surgical smoke is released into the air when energy-based surgical equipment, such as lasers, electrocautery and ultrasonic devices, are used on surgical patients.

Research and improved education regarding the hazards surgical smoke pose to health care workers have led to increased attention in surgical suites nationwide. National standards and recommendations, and new laws in some states, are pressing health care facilities to ensure they have surgical smoke evacuation policies in place to protect their health care workers from the hazardous effects of surgical smoke.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) has required capture of surgical smoke plume since the 2012 edition of NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code. In the 2024 edition, however, Section 9.3.8, Medical Plume (Surgical Smoke) Evacuation and Filtration, now requires health care facilities to capture surgical smoke as close as possible to the point of generation in ORs nationwide.

This is distinct from whole room smoke evacuation that is intended for smoke generated from a fire.

Exposure and health

Like cigarette smoke, surgical smoke can be seen and smelled. It is the result of human tissue contact with mechanical tools and/or heat-producing devices commonly used for dissection and hemostasis.

An estimated 90% of all surgical procedures — including such common surgeries as cesarean sections, mastectomies, knee replacements and appendectomies — generate surgical smoke. Additionally, general room ventilation is not sufficient to capture contaminants at the source and prevent human exposure to this hazard.

OR staff, including surgeons, nurses, anesthetists and allied personnel, face significant exposure to surgical smoke. According to a report from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), OR staff may inhale substances present in surgical smoke at concentrations up to 50 times the permissible exposure limits set by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

The health risks associated with exposure to surgical smoke are numerous and varied. Studies have linked prolonged exposure to an increased risk of respiratory and ocular issues among OR staff. The inhalation of toxic substances in surgical smoke has been associated with both short- and long-term health consequences.

Surgical smoke can contain:

- Particles (e.g., fine particulate matter).

- Chemicals, including aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g., benzene, toluene and xylenes); volatile organic compounds (e.g., acetone and aldehydes [acetaldehyde, formaldehyde]); polycylic aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g., naphthalene, phenanthrene, benzo[a]pyrene and anthracene); hydrogen cyanide; inorganic gases (e.g., carbon monoxide); and nitrates (e.g., acetonitrile and acrylonitrile).

- Biohazard materials, including viruses (e.g., HPV, HIV and hepatitis B), bacteria, blood and potentially viable cancer cells.

Chronic exposure to surgical smoke has been linked to respiratory symptoms, including coughing, wheezing and nasal congestion.

In addition to causing respiratory illness, asthma and allergy-like symptoms, there are documented cases of HPV transmission from patients to providers via surgical smoke inhalation. Moreover, surgical smoke can cause cancer cells to metastasize in the incision sites of patients having cancer removal surgery.

Such findings underscore the importance of proactive measures on the part of health care facilities to mitigate the risks posed by surgical smoke produced in the OR.

Evolving standards

While OSHA acknowledges the hazards related to surgical smoke, no OSHA standard explicitly requires surgical smoke evacuation at the source, and the issue is left to interpretation under OSHA’s General Duty Clause (29 C.F.R. 1910.132, 1910.134 and 1910.1000). The General Duty Clause requires employers to provide a place of employment “free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to employees.”

In addition, under OSHA’s general industry standards, employers are to provide personal protective equipment to minimize exposure to hazards, appropriate respiratory protection to control respiratory hazards, and control exposure to air contaminants at or below permissible exposure limits.

OSHA’s broad “general duty” approach leaves plenty of room for health care facilities to not evacuate surgical smoke at the site of origin during all procedures that generate surgical smoke. Further, the general standards are not effective in truly protecting OR staff from the dangerous health effects of continued exposure to surgical smoke. Facilities may wrongly assume that face coverings and room ventilation are enough to control the hazards to workers’ respiratory systems when the research is clear they are not.

Similar to OSHA, The Joint Commission recognizes the hazards surgical smoke poses to OR occupants but stops short of requiring evacuation at the source. In December 2020, The Joint Commission issued a Quick Safety bulletin confirming that surgical smoke plume contains toxic gases and vapors, such as hydrogen cyanide, formaldehyde, bioaerosols, dead and live cellular material (including blood fragments) and viruses.

The advisory recommends safety actions related to surgical smoke, including implementing standard procedures for the removal of surgical smoke using smoke evacuators and high-filtration masks. The Joint Commission advisory recognizes that surgical smoke is cytotoxic if absorbed into the blood and that facilities should prevent exposure to aerosolized blood.

Given the generalities in the OSHA and The Joint Commission recommendations, there is little national enforcement activity related to surgical smoke evacuation in ORs. In response, the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), the national professional association for perioperative registered nurses, has been working at the state level to enact laws that explicitly require hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers to adopt and implement policies to require use of a surgical smoke evacuation system to evacuate surgical smoke at the source and before it makes contact with the eyes or respiratory tract of the individuals in the room.

As surgical nurses, AORN members spend more time in the OR exposed to surgical smoke than many other members of the surgical team. In addition to the health effects discussed above, AORN members have been shown to suffer headaches (nurses, 48.9%; doctors, 58.3%), watering of the eyes (nurses, 40%; doctors, 41.7%) and coughing (nurses, 48.9%; doctors, 27.8%), as well as sore throat, nausea, drowsiness, dizziness, sneezing, rhinitis and bad odors absorbed in the hair, according to an article titled “The examination of problems experienced by nurses and doctors associated with exposure to surgical smoke and the necessary precautions” that appeared in the June 2016 issue of the Journal of Clinical Nursing.

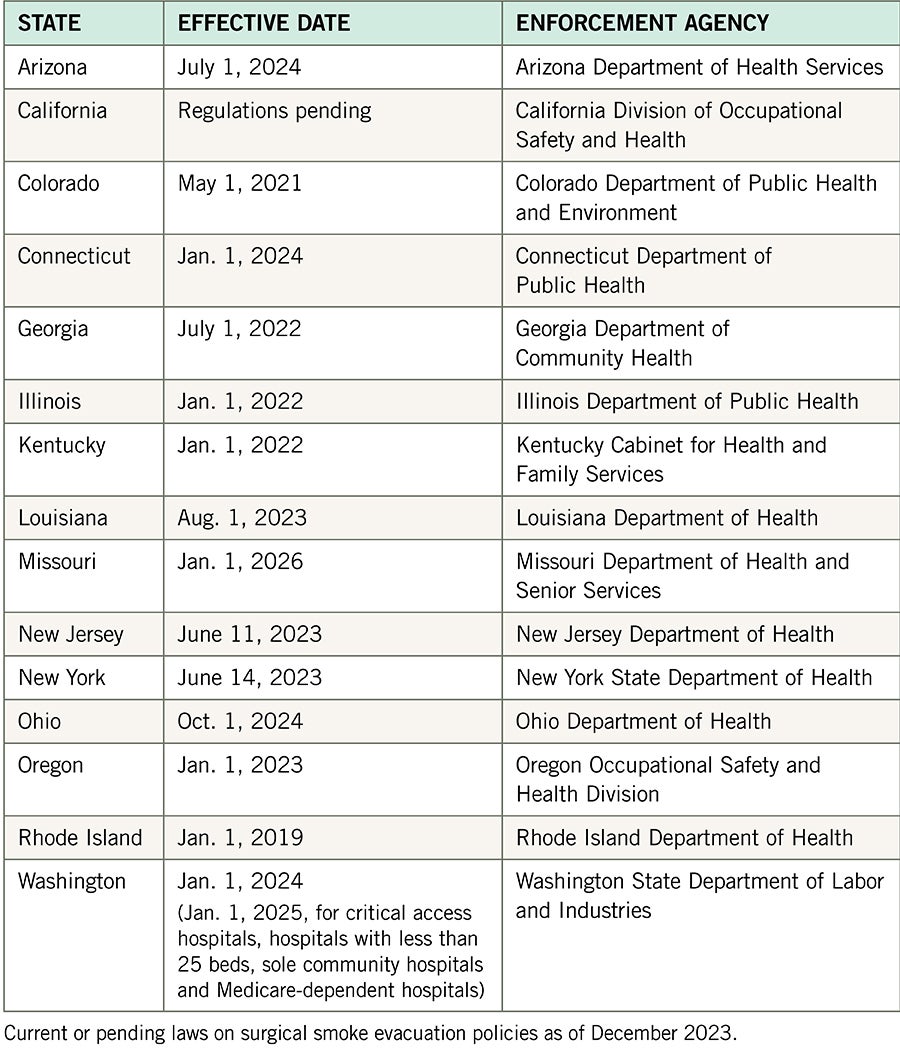

To date, because of AORN and its members’ advocacy efforts, 15 states have enacted laws requiring adoption and implementation of surgical smoke evacuation policies, with some already in effect and many going into effect in the next few years (see the table below). ORs in these states should be using surgical smoke evacuation equipment consistently now or be in the process of coming into compliance for a future effective date. Many more state legislatures will consider similar surgical smoke evacuation laws in their 2024 and later legislative sessions.

Recognizing this gap in state laws and the need for a national approach to the evidence-based health concerns related to surgical smoke, NFPA 99-2024 introduced crucial changes to address the management of surgical smoke, clearly distinguishing point-of-generation surgical smoke capture, evacuation and filtration from whole-room smoke management intended to manage smoke generated from fire. This is consistent with the 2024 edition’s renewed emphasis on creating safer environments for health care workers, aligning with the broader commitment to occupational health and safety.

The updated NFPA 99 requires health care facilities to capture surgical smoke plume as close as possible to the point of generation (i.e., where the energy device contacts the tissue). This is achievable using portable devices and does not require changes to existing facility infrastructure. Facilities may use one or a combination of a dedicated local exhaust system, a connection to the return or exhaust ductwork, point of use evacuator (e.g. portable surgical smoke evacuator device) or a medical-surgical vacuum system. For additional information on these options, health care facilities professionals should access NFPA 99, Section 9.3.8.1, at NFPA's website.

Facilities that have implemented surgical smoke management strategies generally use readily available surgical smoke evacuation tools at the point of use (e.g., portable smoke evacuator device or medical-surgical vacuum with an in-line filter).

Most facilities already have multiple surgical smoke evacuation systems and equipment for their ORs, though they may not be using them consistently. The NFPA 99-2024 code update for health care facilities will prompt facilities to use the evacuation equipment consistently to ensure respiratory safety for the OR personnel in the room.

Clearing the air

As the health care field continues to evolve and looks to reverse trends in provider burnout and health care worker and nursing shortages, prioritizing the well-being of OR staff is paramount to ensuring continued effectiveness of the advancements in health care delivery in surgical suites.

The updated provisions in NFPA 99-2024, specifically the requirement to evacuate surgical smoke as close as possible to the point of generation, reflect a collective commitment to mitigating the health risks associated with surgical smoke exposure and creating safer working environments for all.

The new NFPA 99 requirement to capture surgical smoke as close as possible to the point of generation should be communicated to risk management personnel, health care facilities administration, surgical services department leads, medical staff committees and purchasing departments.

“In our experience, surgical services have the most success in implementing a surgical smoke evacuation program when all stakeholders are involved in policy adoption, staff education and smoke management equipment selection with the vendors,” according to Jennifer Pennock, AORN’s associate director of government affairs.

As surgical smoke evacuation policies gain national attention from organizations and regulatory bodies, and more states look to legislate, evacuating surgical smoke is one immediate and proven way for health care organizations to support workplace safety for health care workers in facilities nationwide.

A step-by-step process for evacuating surgical smoke

According to the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN), the commitment to evacuate all surgical smoke is best implemented with interdisciplinary support and buy-in at a health care facility. These teams are the backbone of technological development for their organizations, executing and monitoring pilot projects based on emerging trends and needs.

Facilities seeking to fulfill the updated requirements of the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, can do so by following a step-by-step process:

- Securing commitment of facility executives, leaders and teams working in clinical care environments where medical plume/surgical smoke is generated.

- Identifying an interdisciplinary team that will hold the responsibility and authority to develop and implement policies and procedures requiring evacuation of all medical plume/surgical smoke.

- Developing an action plan, including adopting a facilitywide policy and procedure for medical plume/surgical smoke evacuation; determining resources needed (e.g., point-of-generation surgical smoke evacuation equipment and supplies); identifying barriers and planning for overcoming them during implementation; agreeing on a timeline for implementation; and determining how success will be measured and maintained (e.g., compliance metrics and an audit strategy).

- Implementing the action plan by identifying and including all members of the affected teams (e.g., perioperative health care workers and teams working in other departments where medical plume/surgical smoke is generated) and providing education about the dangers of medical plume/surgical smoke and details about the facility’s action plan and what each team member’s role is for implementation.

- Auditing and monitoring compliance and celebrating successes.

AORN provides a complimentary surgical smoke-free recognition program to assist health care facilities in creating a surgical smoke-free environment.

About this article

This article was contributed to Health Facilities Management by the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses.

Erin Kyle, R.N., DNP, CNOR, NEA-BC, is editor-in-chief of the Guidelines for Perioperative Practice, and Amy L. Young, JD, is general counsel and director of government affairs for the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses. They can be reached at ekyle@aorn.org and ayoung@aorn.org.