Laying out the case for facility investment

A high-quality facility condition assessment becomes the launching platform for facilities performance improvement and disruptive innovation activities.

Image by Getty Images

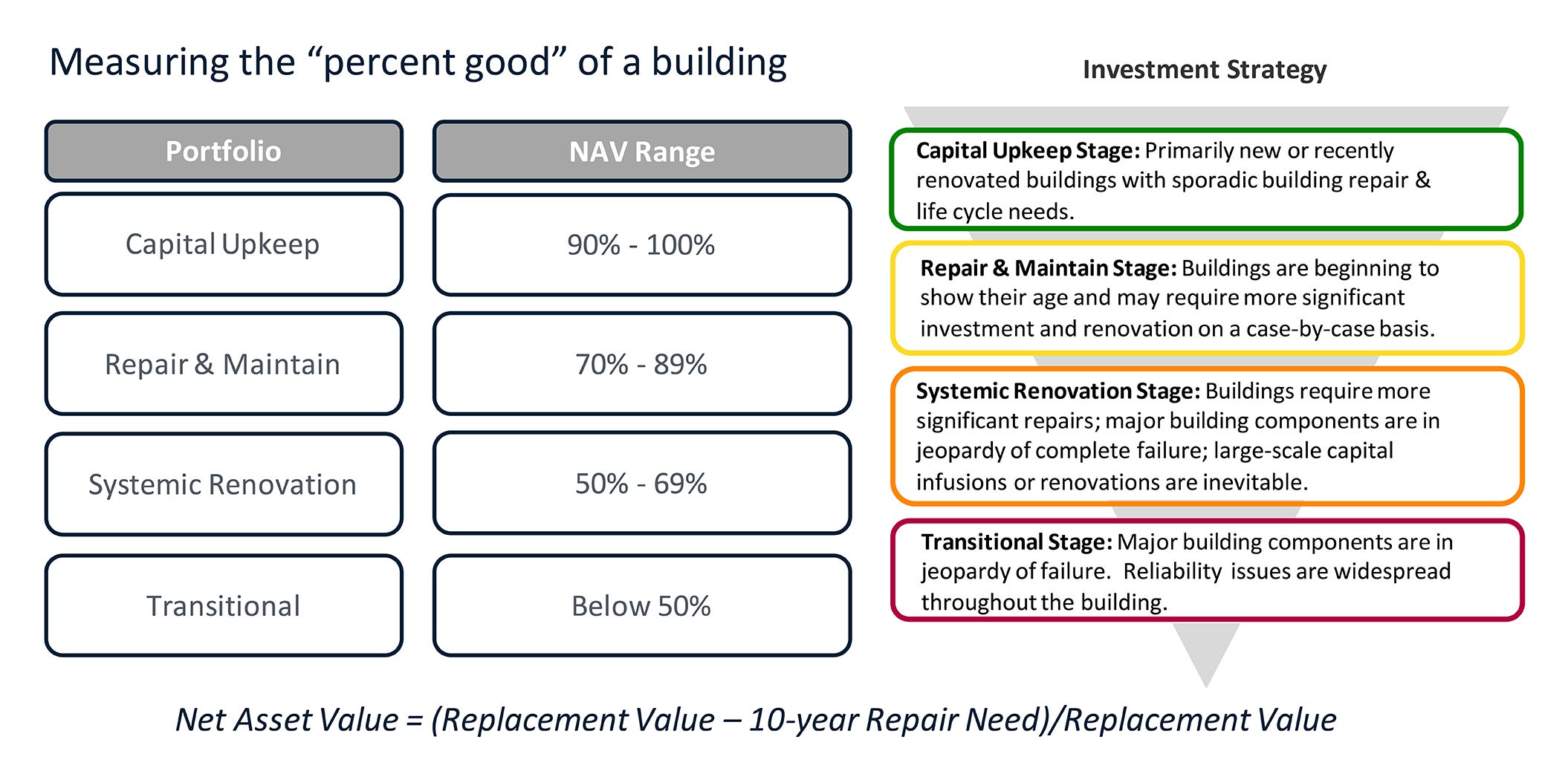

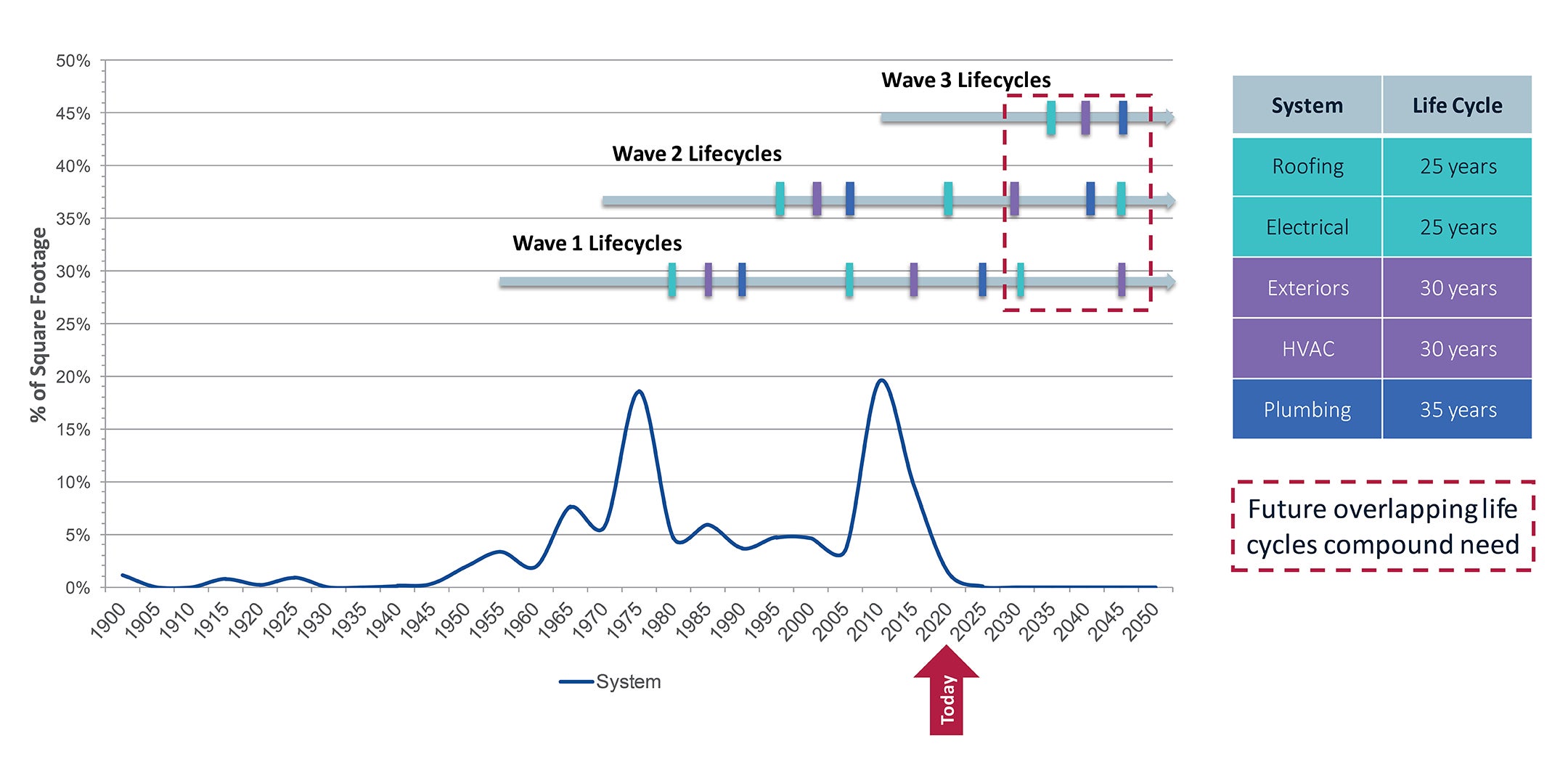

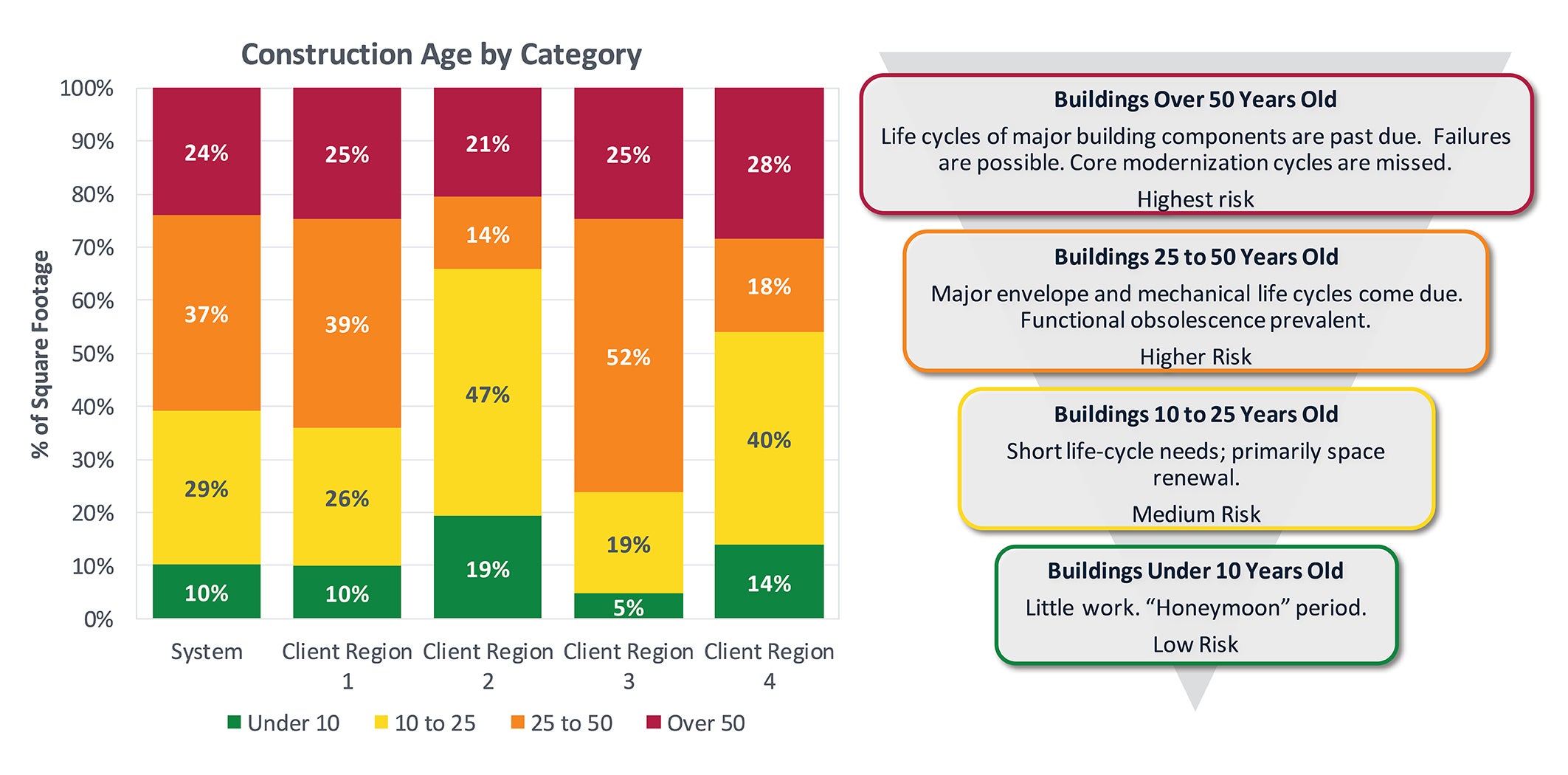

The value of existing buildings and their components represents a substantial item on any health care organization’s balance sheet. Without appropriate investments or a more focused application of increasingly restricted facilities resources, all buildings will age at an accelerated rate and their value will steadily erode.

Unfortunately, that is precisely where many organizations find themselves after years of deferred maintenance, insufficient budget allocations for capital renewal and ineffective stewardship of their facilities. In fact, this chronic underfunding of health care facilities has had such a negative impact on the net asset value (NAV) of hospitals and health centers across the country that it might be time to add a second meaning to the acronym ROI, which typically stands for “return on investment.” Facilities have reached a point where ROI must now encompass “risk of inaction,” too.

Without reliable fiscal stewardship of facilities priorities and a broader conversation about existing and future operational challenges, these physical assets will not remain safe or practical solutions for patient care, and risk management will become unsustainable. When investment doesn’t keep pace with portfolio aging, the result is declining NAV and increased risk to business continuity and critical mission delivery.

State of data

In the past, data was hard to find in health facilities management. And even more challenging was the management of the data available to inform decision-makers on whether to repair or replace.

Facilities managers learned to use their computerized maintenance management systems (CMMS) primarily to win documentation reviews from third-party regulators. The digital document review improved their ability to keep up with the myriad of demands, preventive maintenance (PM) and predictive maintenance (PdM) procedures for compliance.

Only occasionally is CMMS data used for determining if an asset should be repaired or replaced. Often, the facilities manager falls back on anecdotal evidence provided by their trusted mechanics, who are intimately aware of the equipment’s condition.

During this same time, designers, architects, engineers and contractors began a steep climb technologically to improve design, documentation and delivery of health care facilities projects. Computer-aided drafting evolved quickly, as did the information offerings of manufacturers that wanted to keep pace. Contractors had a desire to improve their delivery methods, and many digital products for construction management entered the market. In a matter of two decades, the health facilities management field went from limited access to data to more solutions than can be singularly managed.

The disparate nature of the various data solutions from maintenance operations, as well as planning, design and construction activities, adds a layer of complexity, making most facilities decisions frustrating or even impossible. Data streams from these various activities are not easily manipulated by health care teams, creating many discrepancies, data collisions and lack of aggregation throughout the life cycle of the asset and portfolio.

Steps for best practices

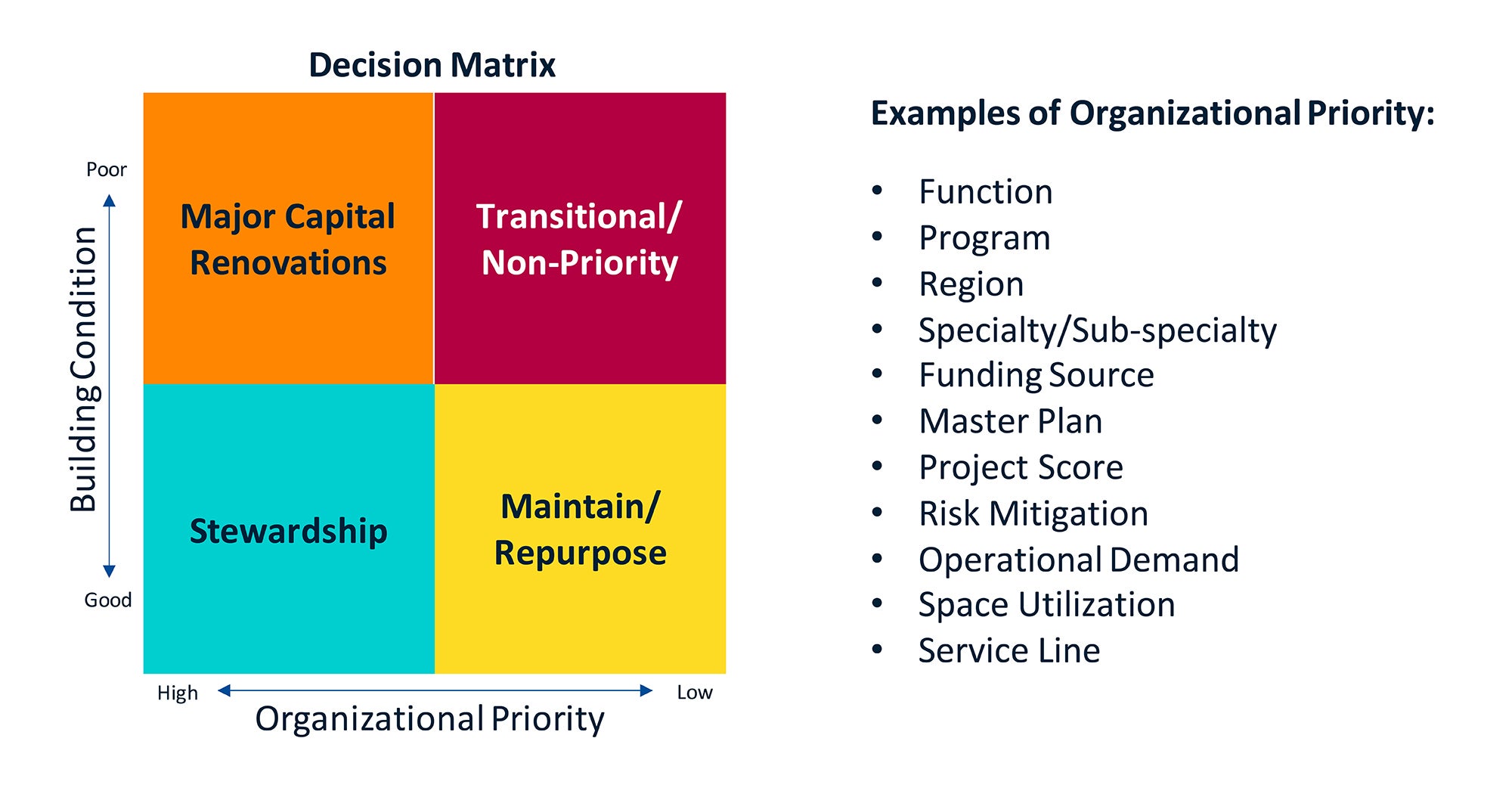

Running a hospital or health care system is not for the indecisive. Decisions need to be made each day to prioritize staff requests and maintain optimal patient care. Data aggregation and transparency inform decision-making models and help to prioritize the health system’s overall mission. Looking at staff requests and other needs through a data-dense lens will allow senior executives to understand how the request is linked to institutional and executive priorities.

When a facilities request is made, documentation is usually provided regarding the age of the asset and its failure rate or mean time between failures, but it is seldom put in terms of what area is served by the asset and its impact on business continuity. Explaining complex facilities concepts in terms and visuals that senior executives both understand and respect is a best practice for gaining additional financial support.

Financial executives are more concerned about obtaining the best value for the next spend rather than dwelling on past investments. However, successful projects that optimize the physical environment and reduce expenses are always a welcome conversation that should be shared early in the budget debate.

Alone, past successes will not shift the outcome unless risk of inaction discussions that prioritize the mission are included. Fortunately, there are steps and process shifts that leaders can implement to reinforce best practices and ensure the risk of inaction is always part of the evaluation. As with most complex problems, the best place to start is developing an understanding of the current condition.

Step 1. Identify the gap between current and ideal states with all key stakeholders. A best practice in problem resolution is gap analysis, where the in situ condition is assessed and documented, the ideal future solution is stylized and the gap between the current and future states for development is identified.

The first step is to identify the missions of the institution and the vision for success as described by the executive team. Most institutional facilities personnel were not included in the development of the mission and vision statements, so it is critical that they have discussions to ensure the facilities managers and their teams understand organizational and mission priorities for the current and future years.

Step 2. Evaluate PM and PdM procedures and develop standards. The next step is to evaluate the CMMS for asset inclusion, veracity of the procedures and the effectiveness of the outcomes. This evaluation should focus on reducing interventions that are not effective and do not add value or prioritize the mission and vision.

This is a great time to ask facilities, operations and maintenance leaders whether they can identify the risk of inaction if the frequency of service is reduced or the procedure is removed entirely. Many activities documented in the CMMS were not the result of a manufacturer’s recommendation but staying ahead of leadership challenges from past incidents or executive and physician mandates.

Evaluation of work effectiveness of both PM and PdM procedures is engineering best practice. This process ensures that frequencies and intervals of service are not reduced anecdotally but instead through a documented evaluation before, during and after the shift occurs. This Lean process ensures that safety is properly prioritized and can be reviewed by peers and through executive oversight.

Simultaneously, or when resources are available, the institution can develop its own design standards and nonnegotiable energy requirements in an owner’s project requirements document. This document gives the owner a formal process to kick off capital projects regardless of the construction delivery method they choose and holds their design teams contractually accountable to the standards.

At the onset of the project, these standards can be discussed to ensure the full team understands what is and is not allowed during the process. Value engineering (VE) submissions that reduce these requirements should not be accepted as they would diminish the project, resulting in another VE — “value eradication.” The document can also include data transmission processes, which digital format is required and which closeout documentation is required, ensuring unwanted data streams are not included.

Both steps 1 and 2 require a substantial commitment from the institutional facilities teams. However, by themselves, they will not resolve the myriad of disparate datasets.

Step 3. Resolve disparate datasets and define needs by completing a facility condition assessment (FCA). Recent trends to cut staffing, reduce third-party service contracts and lower capital allocations add to the challenge and, in most cases, are non-sustainable. There has never been a greater need for informed decision-making that refocuses the facilities investment discussion on mission delivery.

The complications from managing disparate datasets must be addressed in a way that ensures executives achieve their goals, the missions are achieved and there is a margin that can sustain the institution. Clear and concise data that develops the need while achieving other goals is an excellent starting point for change to occur.

With reduced resources, it’s imperative to align the institution behind the challenge and ensure senior executives understand the connection to the mission and financial need in the immediate and subsequent 10 budget cycles.

The next and most critical change process is to complete an effective FCA that connects the various disparate datasets and becomes the bridge and catalyst for change in facility life-cycle management.

The FCA best practice is a curb-to-curb approach that properly evaluates and documents the portfolio from the campus architectural elements, buildings and grounds, capital renewal and deferred maintenance.

A high-quality FCA becomes the launching platform for facilities performance improvement and disruptive innovation activities.

The value of knowing is clarity, which becomes the basis for conversations that change the dialogue to ensure the missions of the institution are prioritized in all operational and capital requests, countering the risk of inaction.

Energy and ops examples

As facilities portfolios have grown over the past decade to address costs and leverage economies of scale, institutions have become acutely aware of their ever-growing energy expenses. What was unaffordable to a single facility or small system now represents a substantial opportunity to invest in energy efficiency during replacements and new construction.

It is important for facilities professionals to understand all the implications of energy efficiency investments, including traditional return on investment opportunities, executive and board stewardship and the evolving environmental, social and governance requirements and commitments. These factors create new documentation and data management challenges for health facilities professionals.

These challenges are magnified as the system grows and acquires existing facilities with different datasets. The cost to standardize products for a large or mid-size system can be staggering and requires substantial investment when other assets are in line for funding. Developing a set of priorities in the form of key performance indicators can lessen the burden and standardize procedures, which can ensure progress is made bilaterally throughout the system.

Operations and maintenance are the steady state of the institution and can be benchmarked for daily activities. If improvements are needed in this group, a systematic and incremental approach should be taken — one that prioritizes process improvement before talent improvement.

Bad procedures can make great employees look marginal, and marginal employees look bad. In most cases, procedures can be modified by both frequency and activities if an efficient engineering best practice approach to improvement is taken. Training can then be developed to improve the human capital engaged in the work.

Interestingly, daily operations are defined by repetitive solutions that can be managed by technicians operating like single contractors within their defined roles. This saves management from unproductive time issuing work orders and gives them more time to evaluate outcomes. The process is defined by its steady state and is easily duplicated from day to day, which is hard to disrupt.

When an institution initiates a project, the intention is disruptive innovation. The goal is always to improve the space.

Improving outcomes

Improved funding outcomes require staff and capital requests to prioritize the missions of the institution. Foundational to this shift is a facilities team’s capability to describe their needs based on outcomes documented in a FCA.

Analysis of the FCA ensures the facilities team can properly Lean up and then provide responsible connection to the supported missions. Reducing the datasets into a manageable stream of information must be a high-priority activity once the foundation for change is laid.

Facilities professionals must become agents of change to ensure sustainable results and drive improvements. By utilizing data informed by their FCA, they add new information about how the asset supports the missions and what would happen should it be ignored or postponed, which is the risk of inaction.

They should start slow, gain momentum and empower the team to fail fast and recover. This will help ensure the needed shift in funding priorities.

About this article

This article is based on a presentation by the author for one of the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s (ASHE’s) Lunch & Learn On Demand programs.

Mark Kenneday, CHFM, CHC, FASHE, is director of health care market strategy and development for Gordian, Greenville, S.C., and a past president of the American Society for Health Care Engineering. He can be reached at m.kenneday@gordian.com.