Managing capital assets in health care facilities

Capital asset reports are generally managed by the chief financial officer with assistance from various professionals, such as the facilities manager.

Image by Getty Images

A health care facility’s decision to invest in any capital asset requires careful analysis and planning as well as knowledge of the drivers that influence future hospital operations. The strategic planning process is a method for hospitals to assess and prioritize their future capital goals against limited financial realities.

Most capital assets have a limited useful service life, and hospitals must be able to calculate that asset’s depreciable cost for their own purposes. The service life should consider the expected wear and tear on the asset and the normal technical or commercial period of the asset. The method of determining the depreciable cost is largely dependent on the productive period of the asset. Numerous factors influence this determination.

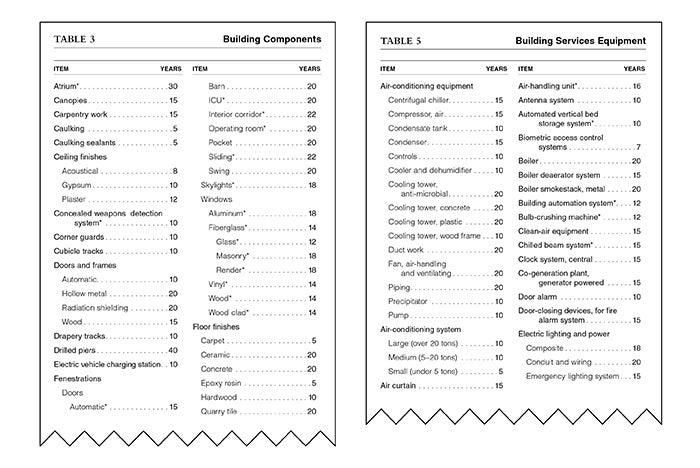

The estimated service life for each asset is presented in the revised 2023 edition of the publication, Estimated Useful Lives of Depreciable Hospital Assets, by Health Forum Inc., an American Hospital Association (AHA) company, from which this article is excerpted and edited. An organization may consider assigning a longer or shorter life depending on usage, types of facility and extenuating circumstances affecting the service life of the asset.

Managing capital assets

Tracking capital assets is a vital component of health facilities management. One must account for the asset from the date of its acquisition throughout its useful life and at its disposal. At the time of acquisition, the cost assigned includes the purchase price and any additional costs incurred to make it ready for use.

During the useful life of the asset, there may arise special circumstances that ultimately affect the remaining cost of the asset, such as obsolescence or the discontinuation of certain health care services at the facility. Other factors affecting the life of the asset may be the result of scrapping, sale, theft or natural disaster. An organization should have the ability to monitor and account for these events.

When accounting for purchased items, it is important to distinguish between capital items whose cost will be recognized over a period of years versus cost taken as a current-year expense. Organizations must also consider the costs and benefits associated with tracking low-cost capital assets.

For efficient and cost-effective accounting, health care organizations should have written capitalization policies that define the minimum dollar threshold and expected service life for considering an item as a capital asset. A capital asset that costs less than this dollar threshold or has an expected service life shorter than the minimum life established by the policy is treated as an operating expense when acquired.

Items acquired in the pursuit of the current period’s revenues and consumed during the same fiscal period are treated as operating expenses. For instance, periodic repairs or routine maintenance made to existing assets to maintain them in good operating condition are considered a current period expense.

Expenditures that materially extend the useful life of an asset should be considered betterments to the existing infrastructure of the asset and be capitalized. For example, significant upgrades or improvements to a heating, ventilation and air-conditioning system may increase its useful life and be considered for capitalization.

A well-established record-keeping process is vital when dealing with capital assets. In health care organizations, this is especially true for the purposes of Medicare reimbursement. Facilities should include appropriate documentation that can help track assets historically.

As new capital projects commence, it may be helpful to monitor and group capital acquisition costs according to assigned capital project lists. Each list should monitor the purchasing of all assets according to an approved capital project number. This number should list all spending for that capital project. It is important to record the purchase order for each capital item as it is added to that project.

Some of the essential components a health care organization should maintain in a capital acquisition log include date of acquisition; asset identification number; a brief description of the asset; serial number, if available from the manufacturer; department, division or location where the asset is used; cost of purchase, or fair value if the asset is donated; estimated useful life assigned; method of depreciation; monthly and annual depreciation amount; accumulated depreciation; and disposition, including date, type and authorization.

For asset identification numbers and serial numbers, unique numerals should be assigned for tracking fixed versus movable equipment. It is a best practice to affix a tracking number to the equipment when it arrives in the receiving department.

The acquisition process

Keeping strict control over the capital acquisition process is another vital component of asset management. Such control must extend to all construction and renovation activities.

Most building construction and renovation projects are complex and span several years. Managing this process requires oversight and ongoing review as various construction tasks move forward under specified timelines.

All building projects should include a construction schedule and a budgeted amount for each phase of construction. Facilities should determine who will approve each phase of the construction project as it is completed.

Ideally, construction bids should include detailed amounts from each of the contractors involved in the project. Facilities should review these bids because they will be useful for future record keeping. As authorization for payment is made for each of the completed components, the organization may want to record and assign a useful life to the assets.

Throughout each project, the individuals managing the capital account should carefully review each approved acquisition. As each aspect of the capital project is completed, an estimated life should be assigned to the asset.

Depreciation begins when the asset is placed into service. Prior to the assets being placed in service, it is considered “construction-in-progress.” Amortization of assets acquired under leases begins at lease commencement, which is defined as the date a lessor makes the underlying asset available to a lessee. The amortization of assets acquired under leases is from the commencement date to the earlier of the end of the useful life or the end of the lease term.

Recording asset costs

Although most hospitals are reimbursed according to the inpatient prospective payment system for operating and capital costs, certain types of hospitals, such as critical access facilities, receive reimbursement for capital-related costs on a reasonable-cost basis. Also, payers other than Medicare may have provisions related to reasonable-cost reimbursement for capital-related costs.

The following guidelines are helpful for establishing the capital asset’s cost allowed for Medicare reimbursement:

- Have written policies for capitalization of assets in place.

- Keep supporting documentation that identifies the purchase price of the capital asset along with any other documentation for additional costs necessary to prepare the asset for use.

- Adjust the purchase price to consider any adjustments received to the price, such as premiums, extra charges paid, discounts or credits, and make sure the purchase price reflects the market value or the prevailing price of the asset as indicated by recent market quotations.

- Base the costs for donated capital assets according to the fair value at the time of the donation.

The disposal of capital assets through sale; scrapping; trade-in; exchange; demolition; abandonment; condemnation; or fire, theft or other casualty can result in a gain or loss on the asset. Whenever a sale or scrapping of a capital asset takes place, it is important to record the extent of the gain or loss. If a gain or loss results, the provider must adjust the cost portion on the “Medicare Cost Report” (MCR).

Other special provisions for the handling of the disposal of capital assets may also apply. For instance, a provider that relinquishes all rights, title, claim and possession of a capital asset with the intention of never reclaiming it or resuming its ownership, possession or enjoyment may sustain a loss by permanently retiring that asset.

In this situation, the provider reports the loss because the asset is being retired from future use and not merely being removed from its current patient care use. The provider must recognize such losses in the year during which the asset was disposed. It is important to check the Medicare Provider Reimbursement Manual for further instructions and clarification regarding these special situations.

Special reporting rules for reporting capital asset gains or losses apply whenever a health care facility changes ownership. Generally, the sale of an asset is greater than or less than the net book value of the asset.

Funding depreciation

Many organizations establish designated depreciation fund accounts for replacing depreciable assets. According to Medicare rules, such accounts are considered valid when the funds remain in the account for at least six months.

Some hospitals may select marketable investment options for these funds, but they should consider the risk associated with these options as well as the availability and conservation of the invested funds. The hospital’s board of directors should approve the establishment of the funded depreciation account, and the board minutes must clearly reflect this decision.

If invested funds generate interest income, facilities should carefully follow the MCR rules. Creating designated fund accounts allows hospitals to avoid improperly using earned interest as an offset for reducing interest expense on the MCR. Improper use of the funded depreciation account or the interest income from this account can jeopardize the special exemption from the offset-to-interest expense on the cost report.

Organizations should keep in mind that the funded depreciation account is established for the purpose of replacing depreciable capital assets that are directly used for patient care or indirectly related to the furnishing of patient care services. They should be careful to avoid any unnecessary borrowing for specific capital projects. Funds established for a particular project should be utilized first before borrowing.

For Medicare purposes, withdrawals from depreciation fund accounts are proper in certain situations. One of these situations is when money is withdrawn for acquisition or replacement of depreciable capital assets. It is improper to borrow money when there are depreciation funds available and to make additional deposits to the funded account after money is borrowed unnecessarily.

At times, health care providers may find themselves faced with the need to borrow money from the funded depreciation account to obtain working capital for operating expenses associated with the delivery of patient care. In these cases, the interest incurred by the general fund is an allowable operating cost if the documentation properly supports the reason for borrowing from the fund and the payment and interest schedules are easily identifiable in the accounting records.

Accurate and authoritative

The AHA publication is designed to be accurate and authoritative.

It is sold with the understanding that neither the authors nor the publisher are rendering legal, accounting or other professional services, for which a competent professional should be sought.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not represent the official positions of the AHA.

Definitions used in health facility capital programs

Commonly used terms associated with health facility capital programs are defined below. More complete definitions are available in the revised 2023 edition of the publication, Estimated Useful Lives of Depreciable Hospital Assets, by Health Forum Inc., an American Hospital Association (AHA) company.

- Amortization. The expensing of a non-hard asset or financial asset over the life of the asset instead of all at once.

- Book value. The monetary amount assigned to an asset. The basis for valuation of the asset is generally the cost plus additional costs incurred to render the asset usable.

- Buildings. Structures consisting of the building shell or frame, building components, exterior walls, interior framing and walls, flooring and ceilings. The building cost can also include a proportionate share of architectural, consulting and interest cost associated with newly constructed or renovated facilities. Interest costs may also be recorded as part of the cost of certain qualifying assets.

- Capital assets. Assets that involve the acquisition of property, plant and equipment. The acquisition cost of the asset meets the organization’s policy for minimum capital cost, if such a policy exists. Capital assets also have economic useful lives that span more than one year and include the asset categories of land, land improvements, buildings, leasehold improvements, equipment and construction-in‑progress.

- Construction-in-progress. A classification category that records the expenditure of capital funds on new construction, land, existing infrastructure or building improvements, or other capital construction projects scheduled for completion in a future period.

- Depreciation. The cost assigned to an asset for a given period associated with a reduction in its value based on the estimated useful life of the asset. This cost is usually determined based on one of several depreciation methods, with health care providers most commonly depreciating the asset evenly over its useful life.

- Fixed equipment. Equipment usually attached to, and often an integral part of, a building. Generally, fixed equipment assets have shorter lives than the building. Included in the fixed equipment category are cabinets; shelving; and wiring and cabling for telecommunications, information technology and other systems. Other types of fixed equipment include the building’s mechanical or system components, such as heating, ventilation and air conditioning; elevators; plumbing; and sprinkler systems.

- Funded depreciation. A special designated financial account created by the health care organization to fund specific future debt service and capital expenditures.

- Impairment. An accounting term used to describe a drastic reduction or loss in the recoverable value of an asset.

- Land improvements. Capital expenditures associated with the land area that is contiguous to, and designed for serving, a health care facility. Capital expenditures for land improvements include assets placed above or below ground and can include a proportionate share of architectural, consulting and interest cost associated with the preparation of the land for newly constructed or renovated facilities.

- Leases. A method of financing capital acquisitions through an agreement providing the right to use an asset, usually for a stated time. Under accounting principles generally accepted in the U.S. and in effect as of the printing date of the AHA publication, leases are generally classified as either operating or finance.

- Major movable equipment. Equipment installed within a building that can be moved if needed. Typically, these assets have a shorter useful life than fixed equipment assets. Some of these items are sufficiently expensive to warrant special tracking, such as imaging equipment and robotic surgery systems.

- Minor movable equipment. Portable equipment that can easily be relocated and is generally less expensive and assigned a shorter useful life than major movable equipment. Some examples include surgical instruments, scopes, cooking utensils and personal computers.

- Net book value. The asset’s acquisition cost (book value) less the asset’s accumulated depreciation, amortization or impairment.

- Useful life. The estimated service period assigned to an asset based on the expected life derived from the use of the asset.

About the publication and its authors

The 2023 edition of the publication, Estimated Useful Lives of Depreciable Hospital Assets, by Health Forum Inc., an American Hospital Association company, is a revision and expansion of 10 editions of the publication released between 1973 and 2018. The estimates developed over the course of all editions have primarily been based on the recommendations of the appraisal firms American Appraisal Associates Inc., Milwaukee; Marshall & Stevens Inc., St. Louis; and Valuation Counselors Group Inc., Chicago. The publisher is grateful to the following individuals for assisting with the development of the 2023 edition:

- Vic Cremeens, MAI, managing director at Integra Realty Resources, Chesterfield, Mo.

- Diana Culbertson, American Hospital Association (AHA), Chicago.

- Andrew Donahue, MHA, CPA, director of health care finance policy and operational initiatives at the Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA), Downers Grove, Ill.

- Jonathan Flannery, CHFM, MHSA, FASHE, FACHE, senior associate director of regulatory affairs at the American Society for Health Care Engineering of the AHA.

- Jennifer Gillespie, AHA.

- Rick Gundling, FHFMA, CMA, senior vice president of health care financial practices at HFMA.

- Scott Hodges, ASA, vice president of fixed assets at OHC Advisors, Los Angeles.

- Patrick Kitchen, RSM US LLP, Chicago.

- Todd Nelson, FHFMA, MBA, chief partnership executive at HFMA.

- John Oliva, director at Kroll LLC, Milwaukee.

- Anthony Placencio, RSM US LLP, Dallas.

- Chabre Ross, AHA.

- David Salinas, MAI, ASA, partner at Healthtrust, Los Angeles.

- James Tellatin, MAI, senior managing director at Integra Realty Resources, Chesterfield, Mo.

- Alyssa Vincent, AHA.

- Ralonda Wright, AHA.

This article was excerpted and edited by Health Facilities Management staff from the revised 2023 edition of the publication, Estimated Useful Lives of Depreciable Hospital Assets, by Health Forum Inc., an American Hospital Association company.