Reducing the risks in ADA compliance

General interior risks of ADA noncompliance include signage, door hardware, door operability and handrail elevations.

Image by Getty Images

Due to the evolving nature of health care services and the need to provide equal access to health care for individuals with disabilities, complying with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in the hospital environment presents unique challenges for health care organizations, designers and contractors.

The ADA is a federal civil rights law that prohibits discrimination against individuals with disabilities in publicly accessed facilities, including health care services. The law applies to all health care organizations, regardless of size, and requires equal access to health care services for individuals with disabilities.

Access is interpreted broadly, and the ADA covers a range of issues related to accessibility, including physical access to health care facilities, access to medical equipment and access to communication with health care providers.

Studies and surveys in numerous health care facilities show that ADA compliance can be a struggle for existing and new facilities alike. Consequently, health care building owners, designers and contractors must play a proactive role in achieving accessibility compliance.

About the ADA

In contrast to a local building code or a guideline, the ADA is enforced by the Department of Justice (DOJ). Designers, contractors and building owners should understand and implement the ADA’s “Standards for Accessible Design." These standards set forth minimum requirements — both scoping and technical — under the ADA. They are reflected in various building codes but not entirely so.

Building codes typically reflect the standards in the areas detailed in the specific codes but do not fully encompass the breadth of the ADA. To further complicate this matter, the standards are not uniform in how they need to be viewed and implemented. They can be implemented differently within areas of a hospital based on the operational functions of a unit or department. Further, states and/or local municipalities may have accessibility requirements that exceed those of the standards.

ADA issues are classified into two categories: architectural barriers and programmatic barriers. Architectural barriers refer to physical barriers that prevent individuals with disabilities from accessing health care services, such as inaccessible entrances, narrow doorways and inaccessible restrooms. Programmatic barriers refer to policies and procedures that prevent individuals with disabilities from accessing health care services, such as a lack of accessible medical equipment and inaccessible communication with health care providers.

Building owners can be cited for ADA issues through complaints filed with the DOJ as well as investigations conducted by the DOJ. Fines for ADA violations can range in value depending on the severity or frequency of the issues and can also include the requirement to make physical changes to the facility. Additionally, the ADA affords individuals (e.g., staff, patients, visitors and volunteers) the right to file lawsuits in federal court.

The current state of ADA citations shows that health care organizations are not immune to ADA violations. In fact, the number of ADA-related complaints filed with the DOJ has increased in recent years.

Health care organizations that fail to comply with ADA regulations can face substantial consequences, including legal citations, fines and reputational damage. Likewise, health care organizations that fail to comply with ADA regulations when designing and constructing health care buildings face risks.

The impact of these risks could be long-lasting, as addressing accessibility concerns can be a challenging task after construction, depending on the design of the building’s floorplates, shafts and corridors. Additionally, making changes to buildings after they have been constructed can be disruptive, if not cost-prohibitive.

The well-being of patients, hospital staff, the public and overall hospital operations may be impacted. To avoid legal citations and fines and to ensure that individuals with disabilities have equal access to health care services, hospitals should prioritize ADA compliance during the design and construction of their health care facilities.

Responsibility for accessibility issues in health care settings extends to all parties, including designers, contractors and facility owners or their representatives. Historically, facility owner/operators assume a large portion of compliance risk regardless of contract language during the design and construction process. The contributions and roles of individual parties include:

Designers and consultants. Designers and consultants play a crucial role in achieving ADA compliance in health care facilities. They are responsible for creating design plans that meet ADA requirements and ensuring that all aspects of the design and construction process comply with ADA regulations.

Designers and consultants should develop ADA design and construction standards that outline the requirements for building health care facilities that are accessible to individuals with disabilities. These standards should include guidelines for designing accessible entrances, restrooms, exam rooms and medical equipment interfaces as well as ensuring that all aspects of the design and construction are compliant with ADA regulations.

Designers and consultants should also be aware of the standard of care for their profession when working on health care projects. To ensure that the standard of care is being met for accessible design, architects should consider having their designs reviewed by third-party consultants.

Designers and consultants may also find value in eliciting feedback on a design from specific patient populations and individuals with disabilities early in the design process. This will help ensure that the design is not only compliant with ADA regulations but also meets the needs of individuals with disabilities.

Contractors and vendors. Contractors and vendors also play an important role in achieving ADA compliance in health care facilities. They are responsible for ensuring that all aspects of the construction process comply with ADA regulations, including accessible entrances, restrooms, exam rooms and medical equipment.

Contractors and vendors should be aware of the contract requirements for ADA compliance and should ensure that they are meeting those requirements throughout the construction process. Contractors and vendors should also be aware of the potential liability for ADA violations, which may result in project delays and penalties.

Owners and owner representatives. Owners of health care facilities are ultimately responsible for ensuring ADA compliance. This includes strategies such as developing and implementing ADA design and construction standards, conducting regular audits of their facilities to identify any potential areas of noncompliance, and developing and implementing plans to address issues identified from the audit process. Owners should also ensure that their staff members are trained on ADA regulations and that policies and procedures are in place to address ADA issues.

Owners may be liable for ADA violations that occur in their facilities, regardless of the contracting language used with designers and contractors during the design and construction process. To avoid these risks, it’s beneficial for owners to prioritize ADA compliance during design and construction.

As part of this prioritization, health care organizations may consider enlisting ADA consultants to ensure that all aspects of the facilities are compliant with ADA regulations. Additionally, hospital owners may want to provide specific staff training, engage an ADA advisory group, add an ADA subcommittee to the environment of care committee and appoint an ADA officer.

Hospitals should also develop ADA design and construction standards or policies that outline the requirements for the designers and contractors of their facilities to help ensure accessibility for individuals with disabilities. These standards should include guidelines for third-party reviews, audits of design standards and surveys of completed projects.

Accessibility risks

ADA compliance is essential for health care facilities to ensure equal access to health care services for all individuals, including those with disabilities. As health care’s buildings and patient needs become more complex, designers and facility operators will need to transition to a more proactive ADA program. Common ADA risks based on citations can be broken down into three categories:

- Exterior risks include the ratio of parking spaces, signage, handrail placement and curb cuts/ramps. These elements are critical for access to the facility and ensure that patients with disabilities can easily and safely navigate the facility. Poor signage or handrail placement can also make it challenging for individuals with disabilities to navigate the facility independently.

- General interior risks include signage, door hardware, door operability and handrail elevations. These risks tend to be at points of transitions; from exterior to interior and/or from different buildings.

- Specific interior risks include door hardware, door opening force, restroom floor areas, sink locations and patient equipment issues. Though automatic opening doors may not be required in all areas, a risk analysis of excepted patient use can help designers and facilities operators evaluate the specific need.

Risks are part of any health care construction project but especially when constructing specialized units such as imaging, pediatric, bariatric and behavioral health units. Each of these units presents unique accessibility challenges that should be evaluated during the design process to ensure a safe and successful construction project:

Imaging care areas. When designing imaging suites, it is important to consider the unique patient interface requirements that may limit accessibility without the assistance of medical staff. Although staff assistance may be required in part of an imaging suite, it is still important to ensure that the suite adheres to other ADA requirements elsewhere.

Additionally, imaging units may use equipment that may not allow for easy patient transfers without the assistance of other medical equipment (e.g., patient lifts). As a result, rooms need to be designed and constructed in a way that allows for ADA requirements and provides additional clearances for transfer equipment. This can help ensure that patients with disabilities are able to access imaging services without difficulty.

Pediatric rooms. Pediatric units require specialized equipment, unique design features and often appealing aesthetics to help with care for these patients. However, aligning accessibility requirements with the needs of pediatric patients can be challenging.

Unlike adult units, pediatric units require equipment that is specifically designed for smaller bodies, considering their unique needs and vulnerabilities. For this reason, it can be challenging to incorporate accessibility criteria into the playful and colorful design features common to pediatrics.

Anthropometrics, or the measurement of human body dimensions, can greatly vary in pediatrics as patients age, whereas standard dimensions can be used for adult populations when planning for accessibility dimensions. This variability can make planning for accessibility challenging and requires a comprehensive risk assessment based on the expected patient population and type of care that will be provided.

Furthermore, pediatric accessibility requirements may conflict with accessibility requirements needed for adult caregivers and visitors. Designers will need to provide design elements that meet the needs of both pediatric patients and the adults who care for them.

Ensuring that pediatric units are accessible not only benefits patients with disabilities but also improves the experience of patients’ families and staff. An accessible environment can reduce stress and improve the overall well-being of those involved in care.

Bariatric rooms. Health care facilities must strike a delicate balance between accommodating patients’ needs and complying with accessibility regulations. This task becomes even more challenging when considering the competing guidelines for ADA accessibility and bariatric accommodations.

For example, bariatric designated restrooms, patient rooms and exam/imaging rooms are necessary in most health care facilities. However, the required room elements and dimensions may be at odds with ADA requirements. Bariatric guidelines often call for more space and support requirements than what is specified in the ADA standards, which can make it difficult to ensure that facilities are accessible and able to facilitate care for all patients.

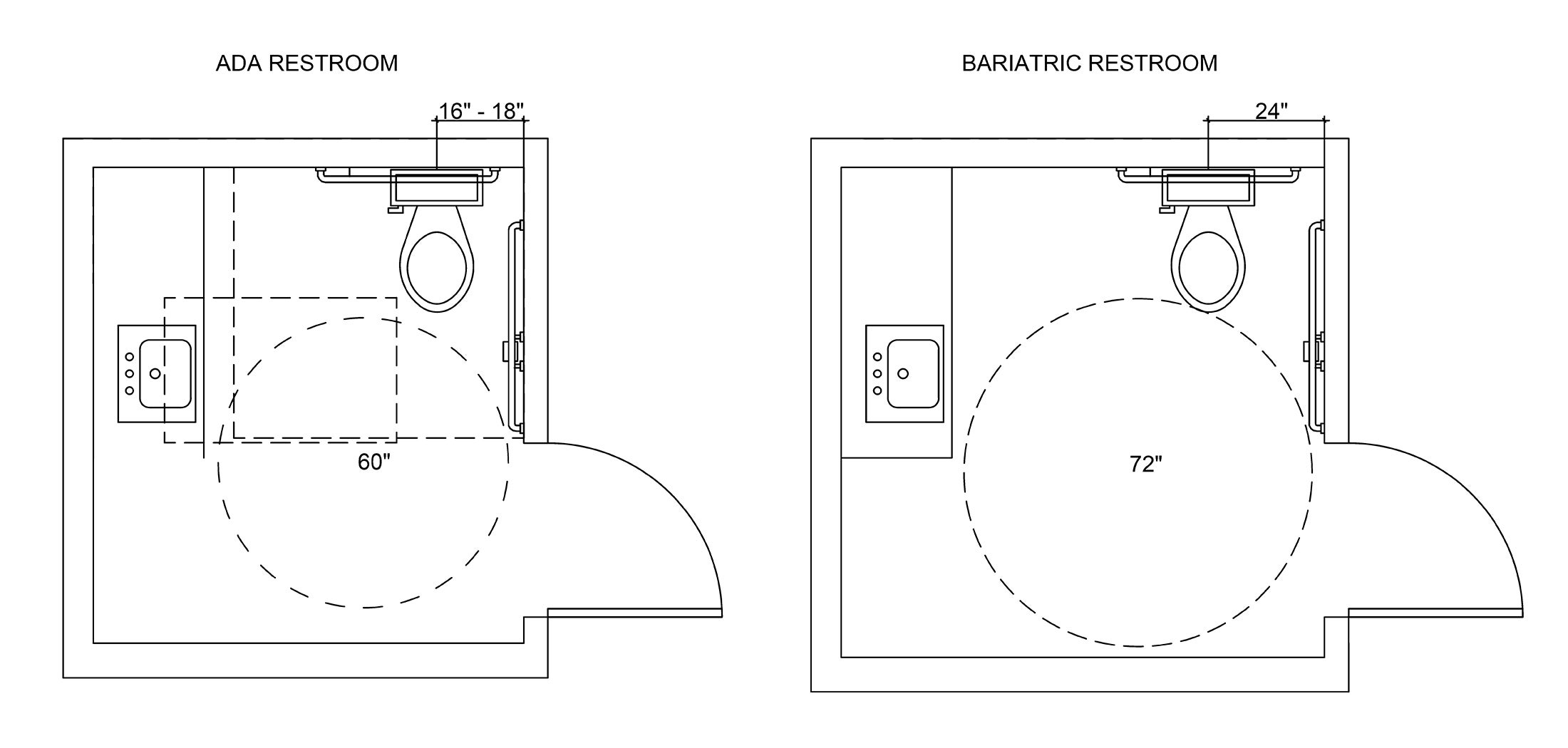

Clearance requirements for these two sets of guidelines often necessitate the creation of separate rooms. Regarding restrooms, for instance, the ADA standards specify that the centerline of the toilet must be 16 to 18 inches from the wall, while bariatric guidelines call for a distance of 24 inches (see graphic above). Similarly, the turning radius for ADA restrooms is 5 feet, while bariatric guidelines require a radius of 6 feet. Both ADA and bariatric guidelines require the installation of grab bars, but the bars for bariatric restrooms must be able to hold at least 750 pounds.

While the ADA standards provide basic and minimal standards for accessibility, it is important to note that these standards should not be considered optimal. For further guidance, facilities professionals should refer to Section 223 Medical Care and Long Term Care Facilities of the ADA standards for scoping requirements of different types of sleeping rooms where patient stay exceeds 24 hours. Where scoping is not provided (e.g., exam rooms), the ADA requires that all these room types are fully accessible.

This also pertains to other common- use areas with public access. Health care facilities should consider the needs of bariatric individuals, ensuring that they have access to safe and accessible facilities that would be in addition to those facilities designated strictly for accessibility. Thoughtfully differentiating these two types of rooms will greatly assist patients, staff and visitors.

Behavioral health settings. Like bariatric rooms, behavioral health and the ADA are two areas with conflicting requirements when it comes to room design. While behavioral health units must be designed to limit the opportunities for self-harm and the presence of ligature points, the ADA standards only specify accessibility elements.

The design of behavioral health units may include features such as anti-ligature hardware, tamper-resistant fixtures, and reinforced windows and doors, all of which can help prevent self-injury and create a safer environment. However, these elements may not meet ADA requirements, such as grab bars, door hardware swings and associated hardware

When designing a behavioral health unit, it is necessary to balance the requirements for safety and accessibility. This often involves conducting a detailed risk assessment that considers the specific needs of the facility and its patients, while also complying with the legal requirements of the ADA.

This may include working closely with the project team (e.g., designers, contractors and vendors), as well as clinicians, hospital leadership and corporate compliance to ensure that all aspects of the care area meet safety guidelines and regulations.

A crucial role

Though the ADA as a concept may be generally understood, its application in health care environments poses a risk to designers, contractors and health care owners based on studies of completed facilities.

Mitigation of these risks varies based upon multiple factors, but acknowledging accessibility as a design challenge should be prioritized.

Adequate compliance with the ADA is an ongoing process that requires the coordination of all parties involved in the planning, design and construction of health care facilities.

Accommodating ADA standards in a behavioral unit’s nurses station

A behavioral health unit nurses station was designed to provide staff with a secure area to coordinate care while maintaining clear lines of sight to patient areas. Unfortunately, the height of the nurses station’s transaction surface did not meet the Americans with Disabilities Act’s (ADA’s) “Standards for Accessible Design.”

To address this issue, the project team collaborated with behavioral health clinicians, hospital leadership and compliance officers, and an ADA consultant to draft a risk management plan. The plan involved installing an accessible transaction surface that met ADA standards in a separate secured area and ensuring that all staff members were trained on ADA regulations. Additionally, policies and procedures were implemented to address ADA issues.

The project team also worked with individuals with disabilities to ensure that the design of the transaction surface met their needs and did not pose any additional risks. This involved the use of 3D modeling and virtual reality simulations to test the design and identify any potential issues.

Ultimately, the project team created a health care environment that is accessible for individuals with disabilities, while also ensuring the security and functionality of the behavioral health unit nurses station.

The risk management plan ensured that all aspects of the construction project adhered to safety guidelines and regulations, providing individuals with disabilities equal access to health care services. If an individual were to file a complaint, this organization could demonstrate its due diligence in implementing best practices for servicing patients and visitors based on need and acuity. However, this does not guarantee that the Department of Justice would not investigate, so proper documentation of the process and stakeholders would be recommended.

This highlights the importance of prioritizing ADA compliance during the design and construction of health care facilities. Although the nurses station did not initially meet ADA height requirements, the project team found a creative solution that was safe and accessible for patients and staff.

About this article

This article is based on a presentation by the authors at the 2023 International Summit & Exhibition on Health Facility Planning, Design & Construction (PDC Summit).

Jamie Staton, NCIDQ, is a construction executive at GE Johnson Construction Company, Colorado Springs, Colo.; Sean Mulholland, Ph.D., PE, FASHE, CHFM, CHC, is assistant professor at the U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado Springs; and Steven Pozefsky, Esq., is associate general counsel at Children's Hospital Colorado, Denver.

The guidance provided in this article shall not be considered professional design or engineering advice and/or legal counsel. The information provided may not apply to a reader’s specific situation and is not a substitute for the application of the reader’s own independent judgment or the advice of a competent professional. The American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) and the authors disclaim liability for personal injury, property damage or other damages of any kind, whether special, indirect, consequential or compensatory, that may result directly or indirectly from the use of or reliance on information from this presentation. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of GE Johnson Construction Company, Children’s Hospital Colorado, United States Air Force Academy, the Air Force, the Department of Defense, the U.S. government or ASHE.