Building a case for internal staffing

The first step in analyzing internal versus external spending is data collection.

Image by Getty Images

Navigating the current health care environment often can feel like steering a great ship through rough and uncharted waters. Most health care executives are proactively seeking opportunities to cut costs and improve productivity across all departments. Can facilities management (FM) departments really cut costs while increasing productivity?

Looking at pages of financial data can be a daunting task. How do facilities managers make sense of all the numbers? Where do they start? How does a facility reduce growing costs while not cutting back on necessary maintenance and improvements? That’s exactly what one health care system discovered after diving deep into a sea of numbers to identify its million-dollar opportunity.

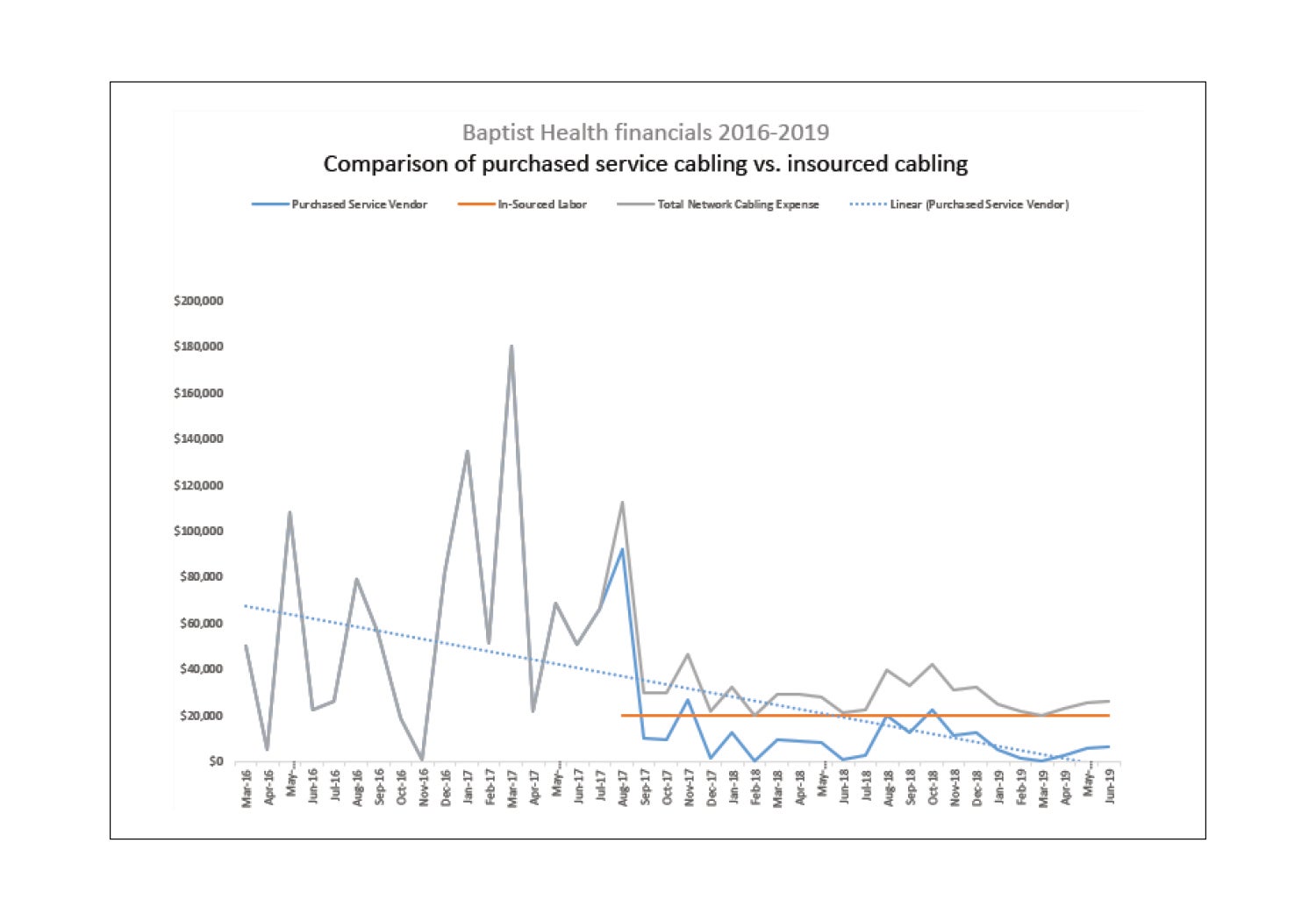

To date, Baptist Health of Arkansas has been able to reduce its operating expenditures by $1.75 million over a four-year period by increasing full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) and reducing outside vendor spending.

Responding to recession

The 2008 financial crisis led to one of the worst U.S. recessions. The crisis spread rapidly, causing global economic shock, resulting in several bank failures, tightening credit, declining trade, rising unemployment rates and the failure of businesses.

Baptist Health, one of the largest health care systems in Arkansas, like many other health care institutions, was not immune to the devastating impact of the crisis. Spending came to a screeching halt. Baptist Health was facing some tough decisions.

Due to financial constraints, several departments across the health care system were mandated to cut 10% of their staff to reduce costs. However, in the FM department, keeping up with repairs, maintenance and regulatory requirements within the buildings was both inevitable and required. This reduction in the labor force merely transferred spending from internal labor to external vendors — and at a premium rate. At the same time, Baptist Health had also brought in a consulting group to help review operating expenses and identify cost-saving opportunities.

One of the recommendations made by the consulting group to senior leadership was to begin outsourcing services, starting with the painting department. At the time, Baptist Health had four in-house painters at a rough cost of $300,000 annually. This included labor, benefits and materials. After eliminating the in-house painting department, outside vendor spending on painting rose to $1.4 million in 2014 alone.

In 2016, to combat the growing rise of external spending, leadership within the FM department began to analyze in detail the department’s income statements across the system. They began with a high-level view of their internal staffing and external spending models.

The team consisted of the vice president of system support services and the FM director. For six months, those individuals met to review their income statements in great detail and to discuss the impact of what they were seeing. One of the first conclusions they drew was that their external spending significantly outweighed their internal spending by 5-to-1; for every $1 paid for internal labor and materials, they were spending $5 for external labor and materials.

After confirming their suspicions with these hard numbers, the team decided it was time to intervene against the push for external labor and build a case to defend bringing these trades back under Baptist Health’s roof.

Insourcing case study

After recognizing the drastic cost variation and presenting the $300,000 versus $1.4 million difference in hiring in-house painters compared to outsourced contractors to system leadership, it was evident immediately that the FM team was on to something with this investigation. Approval was received and the paint shop was staffed within months. In a desire to find more opportunities, the FM group was encouraged to seek out other ways to cut down expenditures by insourcing more skilled laborers.

One of the first trades that was examined as part of this insourcing analysis was cabling. In 2016, outsourced cabling was costing the facility an average of $62,000 per month. After evaluating the hours worked, it was determined that two full-time cabling technicians could keep up with the work demand for a much lower cost of an $18,000 average per month, including labor, benefits and material. FM leadership put together another proposal showing the cost comparison to the organization’s leadership team (see graphic below) and were granted two new FTE positions to start building the in-house cabling crew.

Insourcing efforts also can be in the form of one-time projects. At Baptist Health’s midsized campus, facilities employees shared concerns with the manager that outside contractors were often being hired to perform basic work that they were confident they could be trained to complete without extra credentialing.

To start off with a simple task, the manager looked at the semiannual inspection of batteries in the fire alarm cabinets, identified what competencies and equipment would be needed and set up two technicians to carry out this inspection. Comparing the previous bill from an outside vendor, this inspection cost the facility $720, while the internal team only cost the facility $270. A $450 savings may not seem like a worthwhile undertaking, but this semiannual inspection adds up down the line. Bringing this inspection in-house also increased the morale within the group, who went home feeling a sense of accomplishment and trusted by their organization to perform an important fire safety task.

All this positive work also justified hiring a full-time business analyst with the initial goal of tracking the savings from these insourcing efforts. This analyst now also seeks out new insourcing opportunities and creates and presents the business cases for these new projects.

Cost-benefit analysis

The first step in analyzing internal versus external spending is data collection. An important component of data collection is setting a standard for invoices to accurately cross-compare each vendor against in-house spending. Labor type, labor hours, number of technicians, cost per standard hour or overtime hour, material cost, travel and/or truck charge and sales tax (if applicable) are all key metrics to consider when creating an invoice outline. This guide should then be shared with each vendor to set expectations for formatting future invoices.

Once each detailed invoice is received, it is assigned to a general craft type such as HVAC, electrical, plumbing, architectural and engineering services, construction, physical plant (e.g., boilers, chillers and cooling towers) or roofing, among others. From there, each invoice is grouped into its corresponding high-level craft to help determine which specific craft warrants attention. Then, a spreadsheet is created showing the breakdown of total hours worked and average hourly labor costs of the craft requiring attention each month over the past year.

Next it is time to determine the in-house element. Using the number of labor hours that have been outsourced for this craft over the past 12 months, the number of FTEs required to fill this need can be determined. The market hourly rate of hiring a certified employee in this field also is researched.

To find the total cost for an insourced employee, an estimated cost of benefits provided to each employee by the organization should be included (benefits can cost an organization about 25% on top of the hourly pay). Also considered should be the overhead costs saved from purchasing materials directly from the manufacturer that are currently being marked up by purchasing these items through a vendor.

Once the external versus internal cost over a 12-month period has been established, FM departments can decide whether a specific trade would be beneficial to bring in-house and begin building a case to present to the leadership team.

Building the case

When meeting with the C-suite, one should anticipate the information they will likely seek during the presentation. The more preparation taken to answer questions, the more confident the pitch will be. If administrators respond better to visual aids, simplified bar or line graphs can be used to show a comparison of outsourced versus estimated insourced spending to help drive the point home.

Although most of the presentation should be an objective and data-driven business case, it is also important to highlight some intangible benefits of hiring insourced craftspeople that cannot be quantified into dollars and cents. Employee ownership, pride in the facility and knowledge of the facility are all factors that can play a role in the success of the FM department. Employees may notice and appreciate the fact that they work for a hospital that would rather invest back into the organization than to seemingly waste money on contractors that float in and out.

Creating a process

There are several proactive strategies to improve internal protocols and yield greater productivity from in-house staff long term.

First, it is crucial to build the process. How will these new employees factor into the existing workflow? Who will they report to? What key performance indicators will be examined to measure the success of this new service?

Before bringing these new team members onto campus, the logistics need to be worked out so that they can begin work orders as soon as they are settled into the facility. Where will the office and/or workspace be located? Is there a tool cart available? What additional tools and materials should be purchased?

Like many employees hired into health care FM, this is likely the first time this person has worked in a hospital setting. They should be provided with education and training on general safety, infection control, HIPAA, fire and life safety and other regulatory requirements.

Once the new team is getting settled into the organization, more savings opportunities should be explored. Digging into any one of these crafts to look for opportunities can quickly become an overwhelming task, so it is wise to select one craft at a time and see that project through to the end. After a decision is made to either bring this resource in-house or continue outsourcing, it is safe to go back to the drawing board and start the process again with a different craft.

Delivering many returns

Insourcing may not be the answer for every facility, craft or project. For example, work that is seasonal or specific to one project shouldn’t be included in the analysis of outsourced spending. Additionally, it may be determined that some work that requires specific equipment or training that is not feasible for an organization to purchase also should be excluded from the analysis. Finally, some disadvantages of insourcing include risk of staff turnover, and taking on total responsibility for recruiting, hiring, training and managing the new staff.

However, at the onset of the process, Baptist Health’s FM leadership was able to demonstrate, through development of applicable tools, that bringing additional FTEs in-house would decrease departmental spending for many activities.

After a number of these models were approved and savings associated within department expenses confirmed, FM leadership expanded the model to include in-house construction teams to tackle capital costs as well. The process required the FM leadership team to monitor and regulate third-party expenses across the system for an extended period.

This diligence led to the identification of many cost-saving opportunities simply by leveraging in-house staff on work that historically was performed by outside vendors. To further support its model, the department thoroughly combed through proposals and invoices to validate its initial conclusions that hiring more staff would, in fact, cut costs and reduce overall paid hours.

The FM department built several tools and models to prove and track its findings. In collaboration with the executive team, it established meaningful metrics to use for data-informed decisions. Presented with the objective analyses, leadership agreed to the insourcing model.

Insourcing is an investment that delivers returns beyond financial measures. It creates a culture of accountability and ownership, a collaborative working environment and a talent pool that is enriched with effective training and a business-savvy attitude.

Maintaining bonds with vendors

The goal of bringing more craft functions in-house is not to tarnish or diminish the relationship between a health care facility and its vendors. On the contrary, the goal is to identify cost-saving measures that will allow the hospital to better allocate its shrinking funds to bigger, more impactful projects. If an organization can save money on some of its day-to-day activities, it may gain better leverage to capture some of the avoided vendor costs and put those savings towards a substantial renovation or upgrades down the road.

It also is not a one-size-fits-all approach. As noted in the main article, insourcing may work for some facilities, and even some specific crafts or projects, while outsourcing may still be a good solution for others. Thoughtful deliberation should be given during the analysis of each craft before jumping to the conclusion that insourcing will work for an organization.

At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, Baptist Health, like many other businesses, made the difficult decision to furlough a portion of its workforce to cut some costs, due to postponing elective surgeries and to minimize the potential spread of the virus. The support services division was not impervious to this impact, furloughing almost one-third of the facilities management staff in some departments.

During this stressful time, the facilities management departments across the system had to lean on each other and their strong relationships with outside vendors to keep the buildings operating. And, similar to many companies since 2020, Baptist Health has also seen a decline in staffing across the system. It has been important for the organization to maintain the unshakable bonds with its vendors to get through this strenuous time.

About this article

This is one of a series of monthly articles submitted by members of the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s member tools task force.

Jordan Plyler is facilities manager and Mackenzie Coates is business analyst at Baptist Health Medical Center of Arkansas. They can be reached at jrnorthcutt@outlook.com and mackenzie.coates@baptist-health.org.