Complying with water management program best practices

Fixtures in health care facility water systems that aerosolize water include showers, decorative water features and cooling towers.

Image courtesy of ASHE

Keeping up to date with how standards affect an organization’s water system operations is no small task.

The past year alone saw updates to three published water management industry guidelines: ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188, Legionellosis: Risk Management for Building Water Systems; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Toolkit for Controlling Legionella in Common Sources of Exposure; and ASHRAE Guideline 12-2020. Additionally, The Joint Commission (TJC) issued pre-publication requirements for EC.02.05.02.

Compliance with these standards and guidelines helps hospitals to prevent Legionella and other waterborne-pathogen diseases associated with facility water systems.

This article reviews the importance of water management, outlines existing industry standards and provides recommendations for facilities managers to align with these standards and guidelines.

Waterborne pathogens

Legionnaires’ disease is a type of pneumonia caused by Legionella bacteria. A person contracts Legionnaires’ disease by inhaling or aspirating water droplets containing viable Legionella.

While Legionella exists naturally in the environment, the quantities of Legionella in the natural environment are at such a level that someone with an active immune system is at minimal risk of disease.

The built environment can create perfect conditions for Legionella and other waterborne pathogens to multiply and cause disease. Some factors that exist in the building water system that contribute to Legionella amplification include water stagnation, lack of disinfectant, water temperatures and changes in municipal water quality.

In addition to these water system conditions, there are many fixtures in building water systems that aerosolize water, including showers, decorative water features and cooling towers.

Finally, immunocompromised individuals in health care buildings are the most susceptible to this disease. A building water system that has a well-developed and operated water management program (WMP) will have controls to prevent growth of waterborne pathogens in building water systems.

This is an attainable goal for all facilities, and the existing standards and guidelines provide facilities managers with a roadmap.

Standards and guidelines

Standards and guidelines are important documents that authorities having jurisdiction use to determine minimal standards for safety and protection. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has a long-established standard requiring facilities to establish and maintain an infection prevention and control program designed to provide a safe, sanitary and comfortable environment and to help prevent the development and transmission of communicable diseases and infections.

Water management standards and guidelines with which health care stakeholders should be familiar include the following:

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Memo S&C 17-30. This directive defines at-risk populations and requires accredited health care facilities to have “water management policies and procedures to reduce the risk of growth and spread of Legionella and other opportunistic pathogens in building water systems.”

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188-2021, Legionellosis: Risk Management for Building Water Systems. This standard establishes minimum risk management requirements for building water systems. The scope also covers the water management process for construction of new and existing buildings.

- “Water Management in Health Care Facilities: Complying with ASHRAE Standard 188” monograph.” This American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) monograph, accessible at ashe.org/watermanagement, provides guidance to health care facilities on compliance with ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188 and is available free in a digital form to ASHE members.

- “Developing a Water Management Program to Reduce Legionella Growth & Spread in Buildings.” The purpose of this CDC guide is to help develop and implement a water management program to reduce a building’s risk for growing and spreading Legionella.

- ASHRAE Guideline 12-2020: Managing the Risk of Legionellosis Associated with Building Water Systems. The purpose of this guideline is to provide information for control of legionellosis associated with building water systems. The scope applies to new and existing centralized potable and non-potable building water systems.

- TJC Standard for Water Management Program: EC 02.05.02. This standard is focused on preventing Legionella in health care building water systems through the implementation and ongoing operation of a WMP.

While there are many guidelines for WMPs, they all point to ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188 as the foundational publication. The language may change from one publication to another, but the core message remains the same. A closer look at TJC’s EC 02.05.02 and ANSI/ASHRAE’s Standard 188 illustrates this point.

TJC AND ANSI/ASHRAE

On Jan. 1, 2022, TJC began enforcement of its updated water management standard, EC.02.05.02, which is composed of four elements of performance (EPs). Not all health care facilities are accredited by TJC, and it is important to note that TJC takes direction from CMS, which states all facilities receiving funding from them need to implement a WMP that considers ASHRAE 188 and the CDC toolkit. Still, TJC accreditation is longstanding recognition for health care facilities maintaining a high level of standards for patient safety.

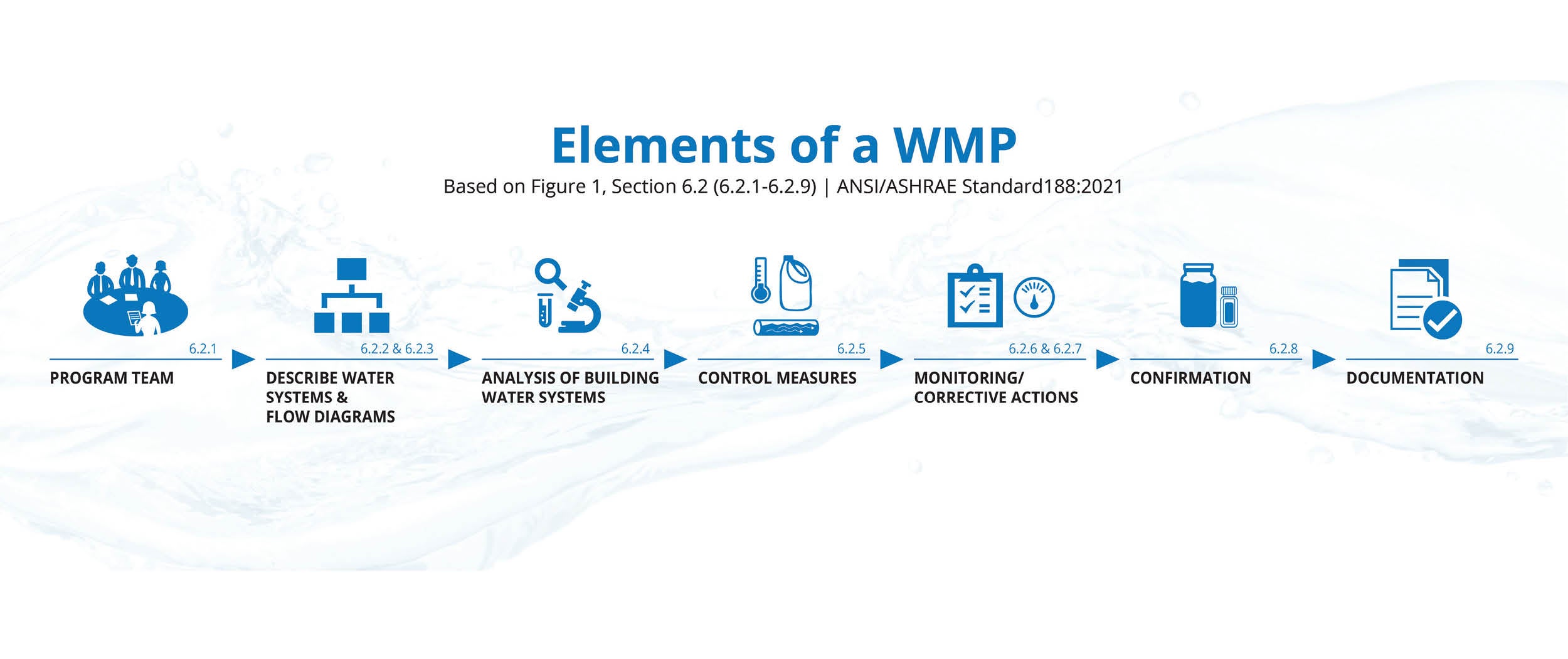

TJC’s publication of EC.02.05.02 represents the ongoing progression of the industry, reemphasizing a compliant WMP as an active program, continually revised by an accountable water management team (WMT). While EC.02.05.02 is new, its basis is not. It is an amalgam of the seven elements first described by ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188 (see the graphic on page 47).

A breakdown of TJC’s EC.02.05.02 by EP, with references to the process established in ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188, includes the following:

- EP 1: Individual or WMT responsible for the oversight of a WMP (Element 1).

- EP 2: WMP development (Elements 2 to 5).

- EP 3: WMP operations (Elements 6 and 7).

- EP 4: WMP updates and construction (ref. ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188, Section 4.2.3 and Section 8.4).

Achieving alignment

Now that the relationship between the two standards has been established, recommendations for alignment with these standards can be reviewed.

Partnerships (reference EP 1 in EC.02.05.02). While the EPs note an individual can run a WMP, ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188 recommends a multidisciplinary team be responsible for development and implementation. Specifically, Annex A provides recommendations for who should be on the health care water management team. While facility management and infection prevention are critical partners, it also is beneficial to include other departments like environmental services (EVS), nursing, risk management, regulatory and compliance, and central sterile. Without an organized WMT at the helm, proper WMP implementation is challenging.

WMP development (reference EP 2 in EC.02.05.02). To develop an effective WMP, a facility must start with a solid understanding of the building water systems, including all processing steps and end-use points. EP 2 of EC 02.05.02 calls for a basic diagram of the water systems, not plumbing diagrams. It is important that these documents are comprehensible to all members of the WMT.

Once diagrams are developed, the WMT needs to develop a risk management program based on the water processing steps identified in the diagrams. There are many approaches to this. One example specific to health care facilities is the ASHE monograph “Water Management in Health Care Facilities: Complying with ASHRAE Standard 188.”

Following this document, the WMT needs to perform a risk assessment of the building water system based on patient population and water-related interactions and capture it in the system analysis summary. During this step, the team needs to also identify areas where water may be stagnant.

At each processing step that was deemed a significant risk, the WMT must decide how to manage the conditions. For this, the WMT selects control measures (e.g., disinfection, heating and flushing). The control measure must include the control location and control limits. The team also must decide how it will monitor that the control measure is within the control limits and the frequency. Lastly, the WMT chooses the procedures to be followed when a control measure is outside of control limits. These are called corrective actions. All this information is detailed in a program controls summary and documented.

This information will provide the team with locations where control measures are to be applied. Control measures should include the location, limits, monitoring method, frequency, corrective action and location. These controls are actions that the WMT has determined will be effective at controlling hazardous conditions. Examples of these include monitoring the residual disinfectant and temperature in source water locations, such as the city incoming water and hot water loops.

Water age. While many factors contribute to Legionella growth in the built environment, a main contributor is water age. When water becomes stagnant (water age increases), it causes the disinfectant in the water to decrease. Stagnant water also can become ambient in temperature. According to the CDC’s toolkit, water without disinfectant and at ambient temperature creates an environment for Legionella to grow rapidly. For this reason, managing water age is critical to maintaining building water safety.

With recent changes in health care operations, there have been unintentional, negative consequences to water safety. As the average length of patient stay is reduced, water age can increase. For example, facilities that include showers in patient rooms that may rarely be used can cause dead legs in the water distribution system. The recommendation in this situation is to partner with EVS to implement flushing upon discharge and self-draining shower hoses or hanging shower heads to allow water to drain from the fixture.

With the pandemic at the forefront of health care workers’ minds, another example of unintentional negative consequences to water safety is drinking fountains. To reduce traffic on high-touch surfaces, many facilities have turned off or restricted access to drinking fountains. The consequence is that infrequent or no usage results in more dead legs in the building water system. The recommendation in this situation is to establish a flushing program for these drinking fountains and ensure they are commissioned appropriately when the time comes.

WMP operations (reference EP 3 of EC.02.05.02). During WMP implementation, each facility should ask themselves the following two questions:

- Is there documentation that proves that the WMP is being implemented as designed?

- Once implemented as designed, is the WMP effective at controlling the hazard?

To the first point, the WMT should have access to all data associated with WMP implementation. Data empowers the WMT to make evidence-based decisions that result in reduced risk, increased defensibility and, potentially, even reduced cost. If the WMT reviews the data and identifies it is not achieving the control limits established, the WMT then reviews the corrective actions documented to bring the program back into control.

A common gap in WMP implementation is not meeting the disinfectant residual control limits. An example corrective action in this situation is to identify the processing step where the disinfectant is being lost and perform flushing until the disinfectant can be achieved. If the point of loss is the incoming main, the WMT should engage the municipality to understand if there is anything it can do to increase the disinfectant level received by the facility.

To the second point, the WMT needs to confirm that the WMP is effective at controlling the hazard. A WMP can be validated the following two ways:

- Clinical surveillance. Infection prevention monitors clinical cases of waterborne diseases to see if the patient contracted Legionnaires’ disease from the facility. A downside to this strategy is a patient needs to contract the disease prior to identifying the WMP is not effective.

- Environmental sampling. This involves taking water samples and sending them to a certified laboratory to confirm the WMP meets validation criteria set by the WMT.

While environmental sampling is the more proactive of the two methods, TJC does not require environmental sampling. Three reference documents in EC.02.05.02 — ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188, the CDC Toolkit and ASHRAE Guideline 12-2020 — recommend health care WMTs consider environmental sampling for facilities providing inpatient services to people who are at increased risk for Legionnaires’ disease. Appendix C in ASHRAE Guideline 12-2020, titled “Testing for Legionella in Building Water Systems,” provides a comprehensive overview of best practices for selecting, collecting and transporting samples; selecting a laboratory; choosing test methods; interpreting results; responding to results; and selecting criteria.

If the WMT determines environmental sampling is the best choice for their health care facility, it is important to develop a validation response plan (VRP) prior to conducting any environmental sampling. The VRP provides a focused response and helps prevent overreactions that may be costly and even make the problem worse.

WMP updates and construction (Ref. EP 4 of EC.02.05.02). A WMP is a living document. It should not be put in a binder and stored on a shelf only to be referenced for an accreditation survey. The WMP must be reviewed at a minimum annually by the WMT. If changes are made to the water system that could have an impact on water safety, the WMP must be reviewed and updated. This includes construction and renovation activities.

Disease prevention

Developing and implementing a WMP makes disease prevention in the health care built environment possible.

By following the seven elements outlined in ASHRAE Standard 188, health care facilities can achieve alignment with industry guidance, including the recent publication by TJC.

Developing a well-functioning, strong water management team

The core of a water management program (WMP) is the team responsible for designing, implementing and managing ongoing operations, including revisions for continual improvement. In 2018, a health care system that understood the importance of a strong water management team (WMT) to the success of a WMP took a comprehensive review of its WMTs.

For this, it used ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188, Legionellosis: Risk Management for Building Water Systems, Normative Annex A, as its guide. The WMT overseeing at an enterprise level identified that multidisciplinary stakeholders, beyond facility personnel, provided relevant input and labor. Over the course of the next few years, three major stakeholders would be integrated into the WMT:

- Infection prevention staff provided a clinical overlay that ensured risk assessments were updated to account for high-risk areas during quarterly environmental sampling events and clinical surveillance.

- Environmental services managers provided significant labor resources and insight for where flushing and water quality monitoring activities should take place based on patient discharge and low census.

- The environment of care committee provided staff training on improving operational safety, effectiveness and cross-departmental cooperation, and meeting with regulatory surveyors.

Integrating these three new stakeholders into the system-level and site-level WMTs drove a realignment of operations. The realignment included how WMT meetings were conducted so that all stakeholders were engaged, educated and self-accountable.

At these “binder meetings,” the WMT would review and update the WMP based on what was documented via a cloud-based data management system. Documentation was printed and added to the binder to serve as an agenda for the team to review. This included program controls, verification and validation data, and necessary corrective actions or validation responses.

The meetings gave site-level WMTs a tool to speak with regulatory surveyors throughout walkthroughs. In 2021, The Joint Commission stated this health care system is following best practices for the upcoming water management standard (EC 02.05.02).

Donnley R. Phillips, CHFM, CHSP, Green Belt, is director of facilities and property management at Northwestern Memorial Healthcare in Illinois; and Erika Wilson, ANSI-certified in sustainable comprehensive water management for the built environment, is a regional manager at Phigenics LLC in Warrenville, Ill.

About this article

This is one of a series of monthly articles submitted by members of the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s member tools task force.