Worker shortages hit health care facilities teams

Like many other hospitals dealing with a workforce shortage, CHI Health Immanuel in Omaha, Neb., is facing challenges in keeping its facilities management department fully staffed.

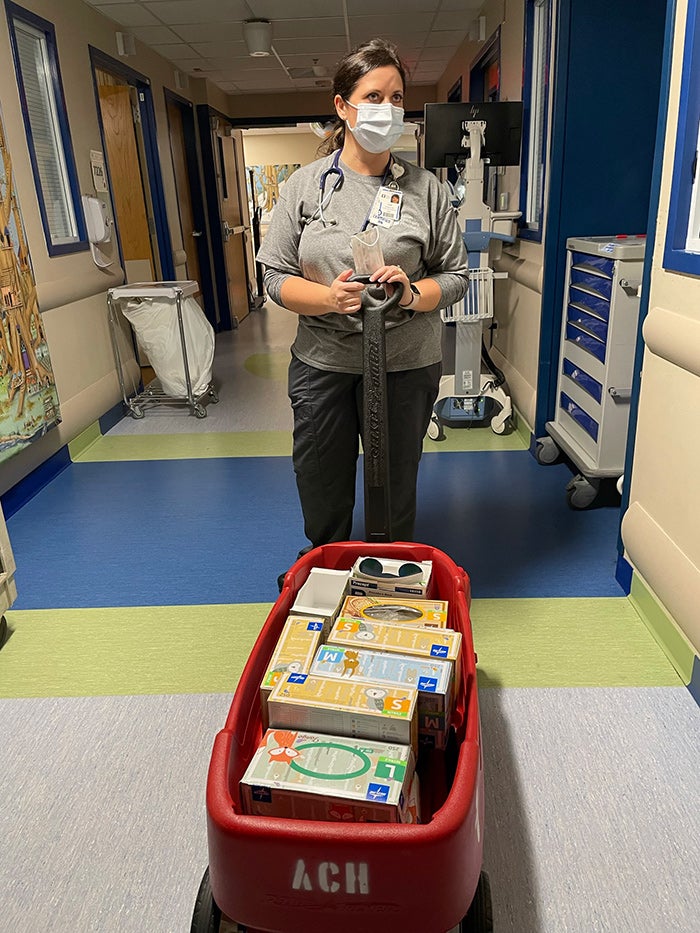

In addition to her role as a manager on Akron Children’s population health team, Samantha Formica, R.N., signed up to help on a patient floor, restocking supplies and tending to patients during a time of short staffing.

Image courtesy of Akron Children’s Hospital

When an engineering position remained open for more than a year, Carol McCormick, SASHE, CHFM, director of facilities at CHI Health Immanuel, and Mercy Hospital in Council Bluffs, Iowa, began exploring new ways to fill the role. Lacking a pool of qualified candidates, she turned to the tried and true. McCormick asked the engineer who retired from the position if he was interested in returning to his previous job. He was, and now works as an engineer two days a week in the department.

McCormick, who uses contractors to fill positions temporarily, said the pandemic played at least a part in the long-dormant opening. At the time, candidates were reluctant to work in a health care position, fearing possible COVID-19 exposure. But the facilities management department faced staffing shortages well before COVID-19, according to McCormick, who says the last few years have been challenging.

“The biggest challenge is filling those engineer jobs that keep the hospital running,” McCormick says. “Facilities is not a department that can put things off. If something is broken or needs to have preventive maintenance, our department has to be there to keep the hospital operating safely. Those positions need to be filled.”

McCormick is not alone. In recent years, factors like a surge in retiring baby boomers, a lack of new candidates and poor succession planning have left facilities departments across the nation struggling to fill open positions.

COVID-19 exacerbated the problem by creating challenges like, stricter regulations and job requirements, tighter budgets and increasing workloads. Factor in pandemic-driven overall job trends like early retirements, mass resignations and long-vacant job openings and the result is a perfect storm that has intensified the facilities workforce shortage.

Two years into the pandemic, third-party contractors who work closely with a network of hospitals are seeing impact of the shortage up-close.

“From my perspective, at its best, the staffing shortage is challenging. At its worst it’s very concerning,” says Jody Reilly, vice president of health care, Limbach Holdings, Inc., a building system solutions firm headquartered in Pittsburgh, that provides technician, engineering and maintenance support to a number of industries, including health care.

“Facilities managers ensure that the environment of care is safe, and that becomes more challenging if staffing levels aren’t full,” Reilly says. “If the environment of care is not safe in an operating room, for example, there can be a direct impact on patient safety.”

While it has long been challenging to fill upper-level roles like facilities director, the current staff shortage is felt primarily in front-line positions like technicians, engineers and environmental services (EVS) staff, and other support services personnel working in cafeteria, food delivery and patient transport.

“Without a doubt, hourly labor is where we are facing the biggest challenge right now. There is an overwhelming need for qualified technicians in facilities departments, and those jobs are hard to fill,” Reilly says. “Technical workers like HVAC technicians, electricians and plumbers are the staff who keep health care facilities running.”

Reilly says the workforce shortage has increased demand for Limbach’s Healthcare Augmentation Program that provides HVAC and plumbing technical support to hospitals, as well as on-site training and coaching for current hospital staff. There is also a greater need to keep staff on longer, he says.

“The model we are implementing now has more of a long-term feel to it,” Reilly says. “This isn’t your traditional service call or preventive maintenance agreement. This is a true extension of the maintenance staff for one reason or another.”

While McCormick doesn’t believe the Midwest has a significant staffing shortage, it is hard for hospitals to fill certain positions since health care is competing with other industries for qualified applicants.

Along with hiring contractors, CHI Health Immanuel and Mercy Hospital also offer staff incentives, including paid overtime and referral bonuses to staff who recommend a candidate who is hired full-time. But such solutions take a toll on finances, often eating into funds reserved for items like preventive maintenance, which impacts the life of the equipment, McCormick says.

“The biggest impact the workforce shortage is having on our hospitals is economic,” she says.

Innovative solutions

Along with facilities departments, support services departments are struggling to fill positions like cleaning, food service and laundry. Akron (Ohio) Children’s Hospital, which is experiencing a hospital-wide employment crisis, took an inventive approach to filling employment gaps.

Through its Helping Hands program, hospital staff are pitching in to help departments facility-wide, working evenings and weekends for the voluntary, paid program.

Scott Wytosick, the hospital’s life safety coordinator, first realized help was needed when he noticed cardboard laying in the hall, which can be a fire hazard. As a life safety coordinator, he wanted to step up to help. He has been working twice a week in EVS in a variety of roles.

“I have done trash pickup, dusting, vacuuming, mopping and other duties that are falling behind,” Wytosick said. “We stick to the simple tasks that don’t require training. I work however long they need me. Sometimes an hour, sometimes four.”

Close to 700 staff members, roughly 10 percent of the hospital staff, volunteered for the program launched in September 2021. “Particularly during the pandemic, so many of us want to help keep the children’s hospital clean and safe,” Wytosick said.

Long-term solutions

Along with stop-gap solutions, long-term strategies are necessary to help hospitals attract and keep qualified staff. The graying of the population and the mass retirements mean hospitals need to make finding new ways to attract applicants a top priority.

Colleges that offer a career path to facilities management are in short supply. More programs like the Community College of Vermont’s Environmental Studies Certification program and Kent State University’s Healthcare Facilities Certificate are necessary, leaders say.

McCormick says facilities professionals also need to promote their field more to younger applicants and work harder to partner with communities to offer vocational training. Internships are another pathway to a facilities career. Currently, McCormick is working with a health facilities intern placed through the Healthcare Administration Program at Creighton University in Omaha with an eye toward filling full-time positions. Organizations like the American Society for Health Care Engineering also offer job resources.

“There is a lot more we can do,” McCormick says. “A lot of the younger generation don’t know about hospital facilities jobs, which offer really great opportunities to young people starting a career. Some end up going into trades with a union job that offers a better salary than we can, which is another factor in attracting employees.”

Reaching students as early as possible is critical, said Charles A. Bacon, III, Chairman and CEO at Limbach Holdings, Inc. He is also a leader in the ACE Mentor Program, a national, after-school initiative focused on teaching a diverse mix of students hands-on skills in technical fields like architecture, construction and engineering. Bacon, who serves as vice-chair of the ACE National Board, joined the nonprofit organization in 2004.

“We go into high schools, many of them in the inner cities, to tell students that they can become an architect, an engineer or a technician and really earn a strong living in a vocational trade,” Bacon says. “There is sometimes a stigma surrounding trade jobs, and we need to get past that.”

Currently, Bacon is working to secure federal dollars to help train students for the frontline, technical positions that are going unfilled in hospitals. He also believes the technology that creates the opportunity for remote work could attract younger applicants. For example, new technology now allows hospital staff to monitor and maintain buildings remotely by talking with onsite staff and guiding them virtually.

“The digitalization of the facilities industry will open up new job opportunities,” Bacon says. “We need to keep moving forward.”