Developing an EVS compliance plan

Environmental services must continually demonstrate compliance with ever-changing laws, codes and standards.

Image by Getty Images

It’s no secret that the health care field is rigorously regulated. It is incumbent upon the effective environmental services (EVS) manager to continually demonstrate compliance with a plethora of ever-changing laws, codes and standards.

Hospitals are responsible for ensuring their programs satisfy practically every legal provision or risk running afoul of the regulatory community (e.g., Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] 42 Code of Federal Regulations [CFR] §482.11, TJC LD.04.01.01).

Statutes, regulations and standards provide the foundation upon which quality health care is built, and beneath which no program should fall.

Compliance challenge

In the words of Charles Kettering, former head of research at General Motors, “A problem well stated is half solved.” So, simply put, the challenge of compliance is developing a program designed to essentially manage practice and operations in a manner prescribed by or conforming to the law.

To help frame a general structure that can reinforce an effective compliance program, EVS managers should consider borrowing the basic outline that underpins The Joint Commission’s (TJC’s) Environment of Care (EC) standards chapter, which includes (EC 1) planning (including risk assessments, policies, plans and evaluations); (EC 2) program implementation; (EC 3) staff training; and (EC 4) monitoring, performance improvement and statistical analyses.

Planning considerations

The first signpost on a compliance journey is developing a sound plan. It’s impossible to play a sport without knowing the playing field and the rules. Thus, it is imperative that EVS managers become familiar with statutory, regulatory and standards-based requirements.

It is important to understand that the thousands of pages of rules, regulations and standards were penned by different people at different times, often to solve different problems. This can create frustrating overlaps, inconsistencies and gaps.

Before managers attempt to carve through the inextricable kudzu of words and esoteric parlance of the legal provisions, they should seek first to understand the intent of these provisions. This should allow for a deeper level of understanding of the “why,” recognition of levels of risk and priority, a better blend of the provisions and a more pragmatic approach.

Within this context, managers can consider the following six habits of getting to the intent of legal language:

- Pay attention to TJC’s rationale and icons.

- Read the appendices and annexes (e.g., the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code®).

- Pay attention to the applications and scope as well as exceptions and exemptions.

- Study the Conditions of Participation regulation’s supplemental interpretive guidelines and CMS survey procedures.

- Invest in regulatory handbooks.

- Assiduous managers also may want to research preambles, congressional or legislative findings, House of Representatives and Senate bill introductions, and historical language.

EVS managers at TJC-accredited facilities should pay particular attention to TJC’s rationale, which is furnished at the beginning of the standard. It provides additional background, justification and text that describes and explains the purpose of the requirement.

The TJC chapter structure also provides icons that accompany the standards, particularly specific standards that require a document are demarcated with an encircled letter “D” icon positioned to the immediate left of the element of performance (EP).

As part of the compliance program risk assessments and establishment of priority, TJC’s current National Patient Safety Goals® (NPSGs) should not be overlooked. Each year, TJC collects “… information about emerging safety issues from widely recognized experts and stakeholders …” This forms the basis for the NPSGs, which are tailored for each specific program.

This pre-planning exercise is designed to group the various codes and standards by subject matter buckets to find common themes and overlaps. For example, the intent and objectives of certain codes pertaining to cleaning can be the maintenance of a sanitary environment, infection prevention and patient safety, proper waste management and worker safely.

Within these subject matter buckets, EVS managers should place the enforcement agencies and governmental organizations, and associated regulations and standards. Common examples include:

- The management of waste. This includes how the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) addresses worker safety as it pertains to managing red bag and sharps waste within the bloodborne pathogen regulation (29 CFR 1910.1030); the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates the management of regulated chemical waste and solid municipal wastes as it pertains to the environment under parts D and C of the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act; and applicable Department of Transportation (DOT) regulations pertain to the packaging of regulated medical waste (49 CFR §173.197).

- Infection prevention. By reference, CMS recognizes and expects EVS programs to conform to organizations and agencies such as the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation®, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses (AORN) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Within the interpretive guidelines of 42 CFR §482.42, there is an expectation that hospitals develop and implement hospitalwide infection surveillance, prevention, and control policies and procedures that adhere to nationally recognized guidelines.

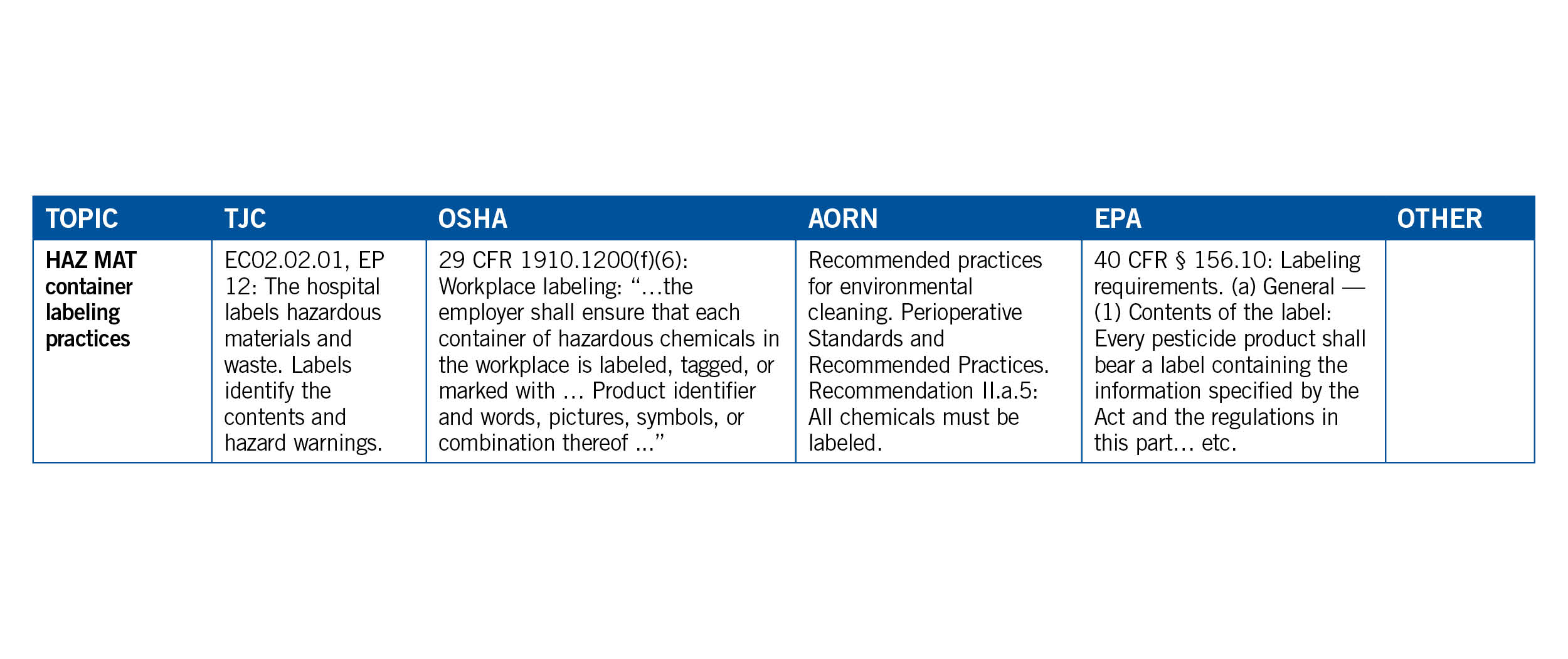

Overlapping and common thread topical themes should almost organically manifest themselves to the EVS manager working through this exercise. They should consider connecting the dots by using a crosswalk linking agencies and standards organizations such as TJC, OSHA, EPA, CDC and AORN to each general subject as illustrated below.

EVS managers should identify and evaluate risks to understand not only potential hazards and deleterious conditions but, from a compliance perspective, current governmental priorities, agency enforcement schemes and liability risks.

The TJC’s EC.02.01.0, EP 1, note states that risks may be identified from “… credible external resources such as Sentinel Event Alerts.” According to TJC literature, Sentinel Event Alerts “…identify specific types of sentinel and adverse events and high-risk conditions, describes their common underlying causes, and recommends steps to reduce risk and prevent future occurrences. Accredited organizations should consider information in a Sentinel Event Alert when designing or redesigning processes.”

In any health care institution, EVS plays a pivotal role in infection prevention and safety in the patient care environment. According to the CDC, hospitals should integrate EVS into the hospital’s safety culture.

Thus, EVS managers should develop management plans, policies and procedures from a platform of interdependence and teamwork to address risks and frame management systems. This includes identifying standards and setting specific protocols for cleaning and disinfection, including the use of technologies and products (per the CDC).

Additionally, using the crosswalk ensures that these standardized policies and procedures align with applicable standards, such as the fundamental EC.02.06.01, EP 20, areas used by patients are clean and free of offensive odors; and IC.02.01.01, EP 6, the hospital minimizes the risk of infection when storing and disposing of infectious waste (also see OSHA 29.CFR §1910.1030).

EVS managers should consider cross-referencing applicable laws and standards within the reference section of the policies and procedures. This goes a long way toward showing surveyors that the department’s policies are in lockstep with their requirements.

One of the basic principles of a high-reliability organization is “deference to expertise.” In light of this, EVS managers should strongly consider involving front-line EVS staff in the development and/or review of policies.

Implementation steps

EVS managers should institute programs and procedures that are predicated on principles and strategies gleaned from the various agencies and standards-based organizations, such as the CDC’s Guidelines for Environmental Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities.

Within this literature, the CDC recommends that strategies for cleaning and disinfecting surfaces in patient-care areas should consider potential for direct patient contact, degree and frequency of hand contact, and potential contamination of the surface with body substances or environmental sources of microorganisms (e.g., soil, dust and water).

The implementation of the EVS compliance program is the nexus of continuous compliance efforts, where the program must delve into the details and get granular to better ensure alignment with requirements. Once intent of the law and standard is discerned, and policy is structured by subject matter similarities and common thread themes, the next signpost is to implement the directive of policy statements and standardized instructional protocols and practices that are in lockstep with the prescriptive details of mandates and literature. This is where the program literally defines compliance: conformity in accordance with rule or order.

Developing checklists and critical task lists are essential to ensuring standardized and consistent processes, minimizing variation and driving accountability.

One example of program implementation that matches rule and order is where the CMS survey procedures for 42 CFR §482.42 instructs surveyors to “…. observe the sanitary condition of the environment of care, noting the cleanliness of patient rooms, floors, horizontal surfaces, patient equipment, air inlets, mechanical rooms, food service activities, treatment and procedure areas, surgical areas, central supply, storage areas, etc.” Given this, the EVS manager would be advised to make every effort to implement inspection check sheets that specifically address patient rooms, patient equipment, procedural areas, sterile supply and food services.

Managers should ensure the implementation of policies and procedures designed to address employee worker safety in accordance with OSHA regulations and applicable accreditation standards. At the very least, EVS compliance policies should incorporate the following OSHA requirements:

- Bloodborne pathogen safety and regulated waste handing (29 CFR §1910.1030).

- Personal protective equipment regulations (29 CFR §1910.132).

- Respiratory standard (especially in light of the pandemic) (29 CFR §1910.134).

To help prepare for the actual survey or agency site visit, EVS managers should create a compliance-evidence binder to assemble, organize and house critical compliance documentation such as staff training sign-in sheets, competency evaluations, policies, permits and certifications, and completed plans of correction from previous surveys.

Training staff

The next step is providing education, orientation and training based on policy, procedure, plans and needs assessments (i.e., making sure staff is packing the right gear). Some, such as the details of required DOT training for EVS staff managing regulated waste and/or tracking documents, can be easily overlooked.

Staff training should address the following required elements according to 49 CFR §172.704:

- General awareness/familiarization training.

- Function-specific training.

- Safety training.

- Security awareness training.

- In-depth security training.

Additionally, EVS managers should document staff competency assessments in accordance with TJC’s HR.01.04.01, EP 1: “Staff participate in ongoing education and training to maintain or increase their competency…” Examples include the process of terminal cleaning, patient room turnover and operating room cleaning between procedures and terminal cleaning.

Monitoring compliance

Finally, performance monitoring includes assessments, performance improvement, statistical analyses and follow-up. To help implement verification procedures designed to enable EVS managers to monitor compliance, managers should simply inspect what they expect; in other words, round the floors and units with a view to validate compliance with policies, regulations and standards, as well as identify any discernable gaps or opportunities for systematic improvements.

During rounding and huddles, EVS managers should take the opportunity to directly observe and verify compliant practices and ask questions related to policy and standardized work processes conducive to consistency, safety and compliance.

EVS managers should actively participate in the facility’s EOC committee and make every effort to utilize the proper statistical analysis tools and methods to demonstrate identifying and taking action to improve the environment. Evaluations of EVS compliance programs should be data driven, illustrate trending analysis over time and determine whether things are getting better, worse or staying the same.

As part of the periodic performance reviews, EVS managers should provide feedback on adequacy and effectiveness of cleaning and disinfection to all responsible health care professionals as well as relevant stakeholders (e.g., infection control and hospital leadership) per the CDC.

EVS managers should present data to their personnel regarding their adherence to cleaning, disinfection, infection prevention and safety procedures by determining the best method to clearly disseminate the information and foster shared accountability.

Lloyd Duplechan is CEO of Duplechan & Associates Healthcare Consulting and a retired hospital COO. He can be reached at duplechanlloyd@gmail.com.