A look at the history of fire safety

The Dec. 8, 1961, Hartford Hospital fire took 16 lives but led to improved codes and standards.

Image courtesy of The Hamilton Archives at Hartford Hospital

As health care facilities engineers know, there can be some long, stressful days at work. A burst pipe, a major piece of equipment down, construction projects falling behind — any number of issues can commonly occur — and never at the right time.

But as daunting as these challenges can feel, they pale in comparison to a fire raging through a facility and taking 16 lives. That is exactly what happened on Dec. 8, 1961, when a fire broke out at Hartford Hospital in the capital city of Connecticut. In its wake, seven patients seeking treatment, five visitors on-site supporting loved ones and four staff members providing optimal care all perished in the catastrophic event.

Prior to the tragic incident, the hospital was described by some, including its architects, as “one of the safest buildings in the world” and “fireproof.” These sentiments about health care facilities are shared by too many today due to modern-day hospital fire safety records. While there has certainly been marked improvement in health care facilities over the years, short memories often are a precursor to complacency.

With the 60th anniversary of the Hartford Hospital fire approaching, it’s instructive for facilities professionals to look at what unfolded on Seymour Street that winter day, the changes that resulted, the current state of health care, and the need for updated codes and standards.

Heat, fuel, oxygen

Fire broke out at the hospital when a discarded cigarette made its way down a trash chute that extended from the subbasement through to the top floor of the 13-story building. Fire smoldered for some time before a door to the chute was opened, providing an influx of oxygen to the fire and igniting gases in the chute that had accumulated. Smoke quickly began to appear on many of the upper stories.

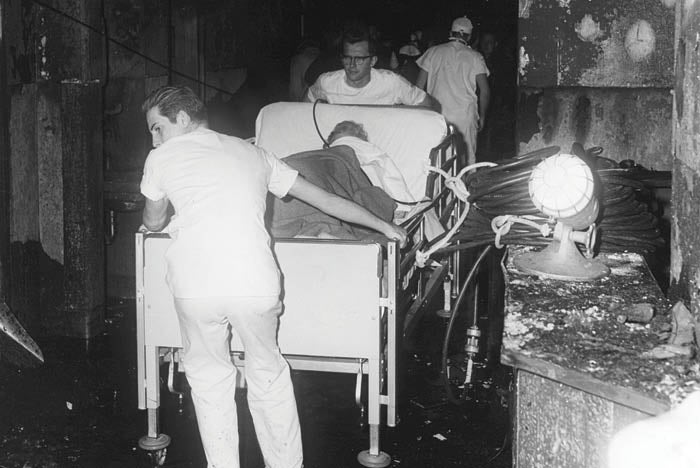

The swift actions of nurses, doctors and other staff ensured that the rest of the patients on the floor at the time of the fire survived.

Image courtesy of The Hamilton Archives at Hartford Hospital

Either because it was not latched or perhaps because it was the weakest link, the chute door on the ninth floor blew off, allowing heat and flames to escape directly into the corridor. Very quickly, fire escaping from the chute ignited the combustible ceiling tile and progressed to both the north and south sides of the building. The burning tiles dropped to the floor and ignited wainscoting, causing fire and heavy smoke to quickly move down the ninth-floor corridor.

While this was occurring, nurses, doctors and other hospital staff raced against time to shut patient room doors, close smoke doors in the hallway that separated the north and south sections from the central corridor area where the trash chute was located, and to secure patients as much as possible. These swift actions ensured that the rest of the 108 patients on the floor at the time of the fire survived.

While eyewitness accounts indicate that both the north and south section smoke doors were closed and latched early on as flames began to spread throughout the floor, the charred results and investigation report proved otherwise.

Investigators found that the smoke door to the north section remained consistently latched throughout the event and effectively limited smoke and flame spread to that wing. There was no loss of life in that northern section. On the south side, however, an entirely different situation unfolded. At some point, the south door became unlatched. This breach subjected the corridor and its occupants to intense fire and smoke. The differentiating factor between life and death that day was whether the corridor doors remained open or shut. Reportedly, the pressure created by the fire in the corridor was enough to cause the rolling door latches to release, and survivors claimed that doors were held or braced to remain closed.

Firefighters were able to contain the fire in a relatively short period of time. Some smoke had migrated onto other floors above, and evacuations were required, but there was no loss of life beyond the ninth floor.

Findings and changes

The Hartford Hospital fire led to immediate changes in the state of Connecticut and ultimately across the nation. The fire investigation revealed issues that had already been addressed in code updates that had been ushered in since the construction of Hartford Hospital, but some other key safety considerations were not required in safety planning before that fateful incident.

A discarded cigarette made its way down a trash chute that extended from the subbasement to the top floor of the building.

Images courtesy of The Hamilton Archives at Hartford Hospital

The investigative report showed that contributing factors to loss of life included the trash chute being open directly to the corridor, flammable ceiling tiles that contributed to high flame spread, a lack of sprinklers, the south corridor smoke door being unlatched, extended dead-end corridors and a lack of positive latching on patient room doors, among other deficiencies.

Within days of the fire, the state of Connecticut limited smoking in hospitals and banned combustible building materials. Use of trash and laundry chutes were discontinued too, unless they were constructed with a charging room that separated chutes from main corridors with fire-safe construction. Over the next few years, improvements were made to Hartford Hospital. Sprinklers were installed in corridors, stairwells and patient rooms, and rolling door latches were replaced with latches that held doors more securely. Moreover, many of these changes found their way into national codes, including the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code®, which at the time was still titled the Building Exits Code.

Fire and life safety codes and standards continued to be updated based on lessons learned that day in Hartford and from other occupancy type safety failures, but the adoption and enforcement of such requirements were still solely handled on a state and local level. This prescription changed with the adoption of the 1967 edition of NFPA 101 in 1970 by the Health Care Financing Association (HFCA), the predecessor to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS).

At the time, HCFA provided a national baseline for the appropriate fire and life safety provisions that hospitals, nursing homes, ambulatory health care, and certain residential board and care occupancies across the country needed to adhere to. Since that time, hospitals, nursing homes, ambulatory surgical centers and related facilities have needed to demonstrate that their fire and life safety programs satisfy different editions of NFPA 101 to meet the requirements of the Conditions of Participation, as defined by CMS. Compliance with the 2012 edition of NFPA 101 is required by all health care facilities today to receive CMS reimbursements.

Codes and standards evolution

When the Hartford Hospital fire occurred, smoking was commonplace in hospitals; in fact, there were very few restrictions in place as to where people could smoke. Patient rooms routinely housed up to four people. Flammable anesthetics were still being used. Fire sprinklers were an anomaly. And hospitals had a very institutional feel to them. Fast forward to today, and it is hard to comprehend that these practices once were the norm.

Combustible building materials and a lack of sprinklers contributed to the spread of fire and smoke during the disaster.

Images courtesy of The Hamilton Archives at Hartford Hospital

Many of the legacy buildings that were constructed at that time or in years prior are still in use today. The majority have undergone renovations and upgrades to give facilities a more modern feel and safer infrastructure. During this same period, the delivery of medicine changed, and patient treatment areas morphed. The equipment being used in health care settings evolved and expanded, and buildings began to be designed with aesthetically pleasing elements that promote healing.

Some of these changes came quickly, while others changed over the course of decades. Generally, codes and standards requirements became more restrictive at first, while being mindful of new technologies or issues that had never been addressed before.

Requirements for fire alarm systems, sprinkler protection, egress arrangements, fire doors, barrier maintenance, vertical opening protection, interior finishes, fire drills and many other considerations were revisited. Lessons learned from fire experiences in health care facilities or other structures were applied. For those areas where sufficient requirements already existed, new construction and existing building compliance became the focus. Referenced standards within NFPA 101 were given greater scrutiny as more people recognized that following one part of a standard without considering all the guidance referenced within that standard leaves a significant gap in safety.

A robust system of enforcement to ensure code compliance was organized for health care facilities. Not only were hospitals subject to local and state inspections, but also to those from CMS, regional CMS offices and/or accreditation organizations granted status from CMS. Hospitals and other health care facilities recognized that to achieve their missions of providing the best possible care to patients, their settings needed to be safe. This led to investments in safety and the development of a skilled workforce to ensure the overall safety of patients, staff and those visiting health care facilities. And, in recent years, there has been a keener focus on emergency preparedness and response.

The health care facility changes precipitated by the Hartford Hospital fire may very well be the best example of the NFPA Fire & Life Safety Ecosystem™ in action. NFPA developed the Fire & Life Safety Ecosystem framework in 2018 to help others identify the components that must work together to help prevent loss, injuries and death from fire, electrical and other hazards. And while fires certainly do still occur in hospitals and other health care facilities, NFPA research shows that the number of total fires and fire deaths in the United States have significantly decreased over the years. Hospitals today average less than one fire death per year.

Smoking is now prohibited entirely in hospitals and even throughout campuses in many cases. And most hospitals are fully sprinklered, with the percentage increasing every year. These are just two of the positive outcomes from the Hartford Hospital fire.

Conversely, hospital patients today tend to be more acute than they were back in 1960. This is largely due to outpatient facilities, such as ambulatory surgical centers, caring for more ambulatory patients. Those seeking care in hospitals nowadays are less likely to be able to take self-preservation measures in a fire. There also is an increased emphasis on improving patient care environments and outcomes. These trends not only improve aesthetics and prognoses, but they also enhance workflows for clinical staff and help to decrease health care-associated infections.

The process of updating NFPA 101 every three years helps to reduce risk in health care settings too. In recent decades, there have been cases for relaxing codes and decisions about concessions that were not allowed in the past. For example, the adoption of the 2012 edition of NFPA 101 included provisions for placement of alcohol-based hand rub dispensers; certain wheeled equipment allowances in corridors; limited cooking facilities open to the corridor; and fireplaces in smoke compartments containing patient sleeping rooms.

While these and other allowances come with certain criteria, it’s important to note that health care’s excellent fire record and long history of recognizing that safety is systemic has played a major role in progress. (See the sidebar on page 30 for additional information on changes since the 2012 edition.)

Preventing another Hartford

Codes and standards and the design of buildings are critically important, but it is the daily work being done by health facilities engineers to comply with standards and to diligently follow through with inspection, testing and maintenance that is the ultimate differentiator.

At the time of this writing, news reports from around the world indicate that nearly 200 people have perished in hospital fires related to COVID-19. None of the concerning events have occurred within the United States, but they reinforce that risk exists and dire consequences can occur. Collectively, health care facilities and the industry that serves them need to keep their eyes on the ball.

Even with the best laid plans and policies, a broken water main or a downed chiller still can occur and disrupt a facilities professional’s workday. But those instances pale compared to the loss of life in Hartford 60 years ago.

More frequent code adoptions can benefit safety and resources

Health care facilities are among the most diligent supporters of the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Fire & Life Safety Ecosystem™, which offers a framework to prevent loss, injuries and death from fire, electrical and other hazards.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has prioritized safety by adopting relevant codes, giving due attention to referenced standards and ensuring that code compliance is enforced. Facilities have responded with investments in building safety, developing a skilled workforce, and placing an emphasis on emergency preparedness and response.

But there is one weak link in the CMS safety chain, and that is the use of dated codes. NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, and NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code®, are revised every three years to keep up with new technologies, trends, research and lessons learned from experience, but federal adoption of these two standards goes back 12 or more years. Changes in the 2021 editions of NFPA 99 and NFPA 101 that would undoubtedly benefit the health care sector include:

- Increased smoke compartment maximum size.

- Coded announcements permitted in fire alarm notification systems.

- Increased maximum suite sizes for patient care non-sleeping suites.

- Increased maximum allowable size of soiled linen and trash receptacles.

- Allowances for microgrids as part of essential electrical systems.

- More structured electrical system preventive maintenance.

- Corrugated medical tubing permitted as new medical gas and vacuum material.

- Operating room fire prevention updates.

Incorporating these changes and others would improve patient care and energy efficiency. Adoption of current standards by CMS also would help health care facility managers save time and energy because they and their designees would not have to compare code editions and figure out how to meet authority having jurisdiction expectations.

Health care facilities have set the safety bar high in the years since the Hartford Hospital fire and should be applauded. But there is still work to do. Adoption of more recent editions of NFPA 99 and NFPA 101 will ensure that health care facilities professionals can effectively and efficiently meet evolving safety needs.

Jonathan R. Hart, PE, SASHE, CHC, is a technical lead and principal fire protection engineer for the NFPA. He can be reached at jhart@nfpa.org.