Designing the post-pandemic hospital

Image by Getty Images

Hospitals have been in the world’s focus since the COVID-19 pandemic began. Long lines of desperate patients, overcrowded emergency departments (EDs), parking lots turned into triage areas — such images were on the news nightly. As the crisis has eased in some areas, what design and engineering lessons have been learned? How will hospitals be different going forward?

“Hospitals are facing lots of design and engineering issues post-COVID-19,” says Jonathan Flannery, MHSA, CHFM, FASHE, FACHE, senior associate director of advocacy for the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE). “Do we need to look at increasing air filtration? Do we need to look at increasing air exchanges? What about patient flow issues? And patient room design? There are so many issues to consider.”

Beyond COVID-19

An important overall issue that designers and engineers need to consider when updating their facilities post-COVID-19 is what the next potential pandemic will be. COVID-19 delivers its dangers via the air, but not all pathogens are transmitted that way. Ebola, for example, is easily spread by surface contact. Thus, an all-risk approach needs to be considered.

“People are jumping to a lot of conclusions that the next pandemic will have the same characteristics as COVID-19,” says Chad Beebe, AIA, CHFM, CFPS, CBO, FASHE, ASHE’s deputy executive director. “For example, I’ve seen proposals that would require 6-foot separation for social distancing. However, we don’t know what variants of either COVID-19 or future pandemics will hold, so a 6-foot separation for social distancing may or may not be appropriate at all.”

Hospital planners may want to begin with a thorough risk assessment, Flannery suggests. This could evaluate the hospital’s ability to deal with any type of widespread pathogen, and identify areas that may need to be strengthened. Even though such a risk assessment would not be definitive, it could guide the planners on where to best invest resources.

For example, even though the next pandemic may not be airborne, air quality issues are always important in hospitals, so investing in improved air handling may be advised in any case. Similarly, some hospitals may determine that creating a devoted infection isolation unit is a worthwhile use of resources.

In any case, hospitals should be prepared to deal with a wide range of potential pathogens, says David Vincent, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP, senior medical planner and principal for architecture firm HKS.

“If we really want to have a holistic approach to designing better health facilities, I think we do need to look at how we address both airborne and surface contact contagions,” Vincent says. “If you remember at the front end of this COVID-19 crisis, they were saying that it was spread [primarily] by surface contact. I think, ultimately, if we want to do a comprehensive job, we have to look at solving both problems.”

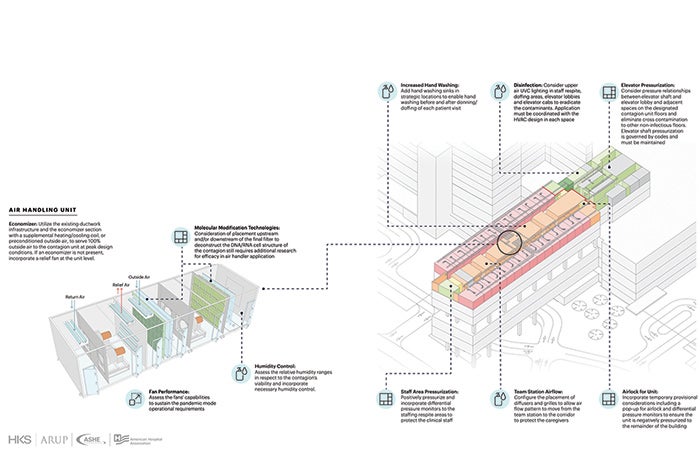

Mechanical systems

Managing the airflow in the hospital will probably be important in any future pandemic and, fortunately, most hospital air handlers are already solid performers, Flannery says. Where many can be improved is air filtration, he says.

“Probably the most important thing to do is look at filtration,” Flannery says. “If the air handler can’t handle a MERV 14 filter or better, they should consider upgrading it.”

Improving the filtration on an existing air handler requires adjustments in other areas, he says. A filter creates more friction in the system, which reduces the quantity of air coming out. Thus, the fan may need to be adjusted to a higher speed.

Resources

Another way to increase filtration is through the use of stand-alone air recirculators with HEPA filters, says Jake Katzenberger, PE, HFDP, LEED AP, mechanical technical leader and associate at Henderson Engineers, Lenexa, Kan.

“You don’t have to necessarily upgrade an entire air handler or have filtration in your air handler to mitigate some risks from an airborne contaminant,” Katzenberger says. “By adding a HEPA recirculating unit with four air changes in a room, that can significantly decrease the risk of spreading an airborne disease, because you are getting those contaminants out of the air before they can be spread. I think facilities could stockpile a certain number of those HEPA recirc units so they can deploy to certain areas if they need to during some sort of surge event.”

Patient flow

Another issue at the intersection of hospital design and pandemic management is patient flow. Hospitals in general are not designed to restrict movement, and that usually is not a problem. But during COVID-19, hospitals learned that the more infected patients moved around, the more likely they were to spread the virus.

“The fewer people that you have to pass, the less risk you have of transmitting the virus to them,” Katzenberger says. “You have a shared risk if you’re in the same space with someone else.”

A design solution to that is creating spaces and corridors that encourage unidirectional flow, Vincent says. One-way corridors — similar to the one-way aisles that appeared in many grocery stores — can reduce the risk of pathogen transmission between people. But the solution doesn’t only work for airborne risks: Unidirectional flow also can reduce surface transmission.

For example, in spaces where staff remove their soiled personal protective equipment (PPE), having an exit that is separate from the entrance prevents people from touching garments or surfaces that may harbor the pathogen. In fact, one of the protocols for proper decontamination is unidirectional flow, Vincent says.

“That simple idea of unidirectional flow is extremely important to maintain for infectious diseases that are spread by surface contact,” Vincent says. “In the Ebola crisis, when it happened at Presbyterian Dallas … we needed to come up with a room design that allowed for the unidirectional flow. It’s called an exit room. That exit room is after the person takes their gear off, that gear goes into the trash and they go out one door to the shower and then change and leave the suite. They don’t go back the way they came in.”

Managing patient flow can extend with design changes throughout the hospital. When a patient enters for any procedure, they typically visit a registration table, a waiting area, an exam room, a lab, and perhaps a pre-op and post-op room, among other spaces. Each stop increases the potential for pathogen spread, says Mark Chrisman, Ph.D., PE, health care practice director and principal at Henderson Engineers. If the patient intrahospital travel could be reduced — such as by having some functions combined — risk would go down.

One way to reduce patient traffic is by encouraging the use of telehealth, Chrisman says. “If you eliminate folks having to come to the hospital via telehealth, you’ve completely eliminated the risk of them spreading the virus,” he says.

Hospital entryways

One of the key issues that needs to be considered in the post-COVID-19 hospital is better control of the hospital’s entryways, Vincent and Katzenberger agree. This control is both a design and engineering issue.

For example, the typical ED vestibule is a tiny space that is not designed to hold people, Katzenberger says, but it became a screening area during COVID-19. “We will have to change how we design that vestibule to be more of an occupied space from a comfort standpoint, and also probably have additional requirements like power and a built-in desk,” he says. “It’s going to have to be thought through like a permanent solution.”

Furthermore, once people get past the vestibule, future EDs will likely have separate areas for people to wait in. People exhibiting symptoms of the pandemic could be separated from other patients, which would help prevent spread and better facilitate tracking of those pandemic patients, Katzenberger says.

Chrisman says that when his young children visit the doctor, there is a sick waiting space and a well waiting space. “Why don’t we have that in the emergency department?” he asks. “Because it wasn’t required. But, while we’re moving forward, maybe we can do that.”

Vincent envisions an even more thorough design change to the ED. He says the concept of a “multimodal entry portal” could help steer infected patients into the right path and away from well patients. This entry could use technology such as air sensors or biometric identification to sense patients who are ill before they enter the ED waiting room.

“The nature of how people present at the ED needs to be better addressed, because the presentation is very different depending upon the event type, and the response needs to be very different,” Vincent says. “An infectious disease happens slowly over time and gets to the point where the infection rate is very high and then, all of a sudden, a lot of people come to the ED. That presentation is completely different than the chemical plant down the street that just blew up and 50 people got burned or something similar, and how the ED entry handles them must be different.”

Operating rooms

Once a patient passes through a hospital entryway, the operating room (OR) or suite is the next stop for many. Those spaces also are changing because of the COVID-19 experience.

Infection prevention is naturally a primary concern in the OR, and one important tool in that regard is positive pressure, which keeps airborne pathogens in the corridor from entering. But if the patient on the operating table has an illness spread by airborne pathogens, positive pressure clearly is not ideal because the pathogens may spread to the corridor.

One potential design solution is to create an anteroom between the OR and the corridor, Katzenberger says. The OR could have positive pressure to the anteroom — keeping pathogens out of the OR — and the anteroom could be exhausted to create negative pressure with the corridor and remove any pathogens coming from either direction. The challenge, especially in an existing building, is that there’s rarely room in an OR suite to add an anteroom without eating into the OR space.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) offers guidance for handling OR patients with tuberculosis (TB) and measles that could apply to patients with other infectious diseases, Flannery says. The CDC guidance is to schedule operations on patients with TB or measles at the end of the day and put OR staff in appropriate PPE.

Patient rooms

Flexibility is the key to patient rooms in the post-COVID-19 hospital. For most of the time, patient rooms are used for the basics — housing someone who needs attention but not constant acute care. But during a surge, a flexible patient room could be transformed into a space that facilitates more in-depth care, up to intensive level.

“During the COVID-19 pandemic, we saw the need for rooms that could serve a patient from the time they came in — when they didn’t need critical care — to the time they needed more attentive care and then back,” Flannery says. “But moving them around was a bad thing because they were COVID-19 positive, so having a room where those patients can stay the whole time is something every facility needs to consider.”

A flexible patient room design would be larger than a regular room so that it could accommodate more equipment, Flannery says, and the utilities would need to be more robust. One utility that was in special demand during COVID-19 was oxygen.

“We never anticipated the number of ventilators that were needed,” Katzenberger says. “Medical gas systems were taxed way beyond what was expected.”

Ventilator capacity can be increased in several ways. For one, the vaporizers on the oxygen cylinders can be oversized, which allows more oxygen flow, he says. And patient rooms can be retrofitted with more gas outlets so that more ventilators can be served, if needed. Additionally, capacity can be expanded if the gas pressure can be safely increased.

However, the primary challenge is expanding the gas piping in an existing facility. If the pipes are not able to carry more oxygen or pressure, expanding the vaporizers or adding outlets won’t help.

“The size of the main piping is really your limiting factor, and that’s not easily rectified in an existing facility,” Katzenberger says. “You can create a solution by taking a main and routing it outside the building and building an enclosure around it, but no one likes that from an aesthetics standpoint.”

A short-term solution to the oxygen problem is simply to add temporary oxygen manifolds to the patient care area, Flannery says. This could increase oxygen capacity without construction.

Another way to make a patient room more flexible is to adjust the air handling so the room can be made negative pressure, Katzenberger says. Ideally, an exhaust grille would be added above the patient’s head to create the most effective air flushing, though the noise of the grille might disturb the patient.

Special pandemic units

Another important consideration in designing the post-COVID-19 hospital is considering spaces that are devoted to pandemic patients. Many hospitals have some type of isolation room, but a key to future design of such units may be to keep them together, Vincent says.

“Right now, we have what I’d refer to as distributed isolation rooms,” Vincent says. “A hospital might have one or two rooms per unit, so they have 24 rooms, but they’re spread over 12 units. That makes it much more difficult to manage during a pandemic.”

The concept of isolating pandemic patients to one part of the hospital could extend to dividing the entire hospital, he says. A partially divided hospital could work if patient and staff traffic between the sectors could be limited.

Katzenberger says that such a division could also be accomplished by utilizing buildings outside the main hospital, such as surgery centers or outpatient treatment facilities. The main hospital could be devoted to pandemic care, and regular patients could be treated in the outlying buildings, he says.

Better prepared

The overarching concept regarding hospital design post-COVID-19 is that hospitals now have the opportunity to use these lessons to prepare for the next time.

During the Ebola crisis in 2014, some hospitals began working on negative pressure isolation units or biocontainment units, Chrisman says. But, for the most part, those projects stopped when the Ebola crisis passed.

“Many of the people involved wished they would have gone through with some of those projects because it would have helped this time around,” he says. “And, hopefully, people are going to take this seriously moving forward, knowing that this won’t be the last time we’re in some sort of worldwide pandemic.”

Price doesn’t guarantee success

As with any decision, when a health care facility considers design or engineering changes to prepare for the next pandemic, the budget plays a major role. But sometimes the big-ticket items aren’t the solution.

“I think the key is focusing on manageable solutions that have a measurable result,” says Jake Katzenberger, PE, HFDP, LEED AP, mechanical technical leader and associate at Henderson Engineers, Lenexa, Kan. “I think those solutions get implemented, and the implementation is maintained over time. Sometimes solutions that have a huge cost and huge manpower change get put on the back burner once the main crisis load is over. So, thinking small kind of leads to bigger long-term changes.”

An example of a low-budget item that could have an important effect is a pre-screening system that uses technology instead of significant renovation. For example, a system could add a pre-screening function to its app that asks patients about symptoms before they enter the hospital. “The app could say, ‘If you’re feeling any of these symptoms, stay in your car until we call you,’” says Mark Chrisman, Ph.D., PE, health care practice director and principal at Henderson Engineers.

Similarly, when designers create hospital spaces intended for pandemic use — such as isolation rooms or additional intensive care unit space — it may be financially expedient to design them so they can be used as regular patient or exam rooms during normal times. “It’s a tricky balance for the hospital financially to build out a bunch of space that may or may not be used,” Chrisman says. “We’ve been seeing more and more design of spaces that can flex overnight or during a patient surge.”

Says David Vincent, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP, senior medical planner and principal for architecture firm HKS: “It’s all about the risk versus reward. How much money do we want to put in for what could be a never event?”

Working with the community for help

When hospital leaders plan for the next pandemic, they should consider leaning on the community to take the lead in some cases, says Chad Beebe, AIA, CHFM, CFPS, CBO, FASHE, deputy executive director of the American Society for Health Care Engineering.

“I think the way to prepare for the next pandemic is to advocate that hospitals aren’t the best place to take care of pandemic-related patients,” Beebe says. “The better place to take care of these patients in a pandemic would be by the community, given that the alternate care sites that are likely going to be set up are going to be community sites. Hospitals are better suited for taking care of acute care patients, and they should continue operations as normal during the next pandemic.”

David Vincent, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP, senior medical planner and principal for architecture firm HKS, agrees that community-based sites will be needed in future pandemics. But enough clinical personnel may be an issue, he says. “The rate limiting factor, I believe, is still the number of clinicians you have to treat patients,” he says. “Whether or not I’m being treated at a converted convention center or whether or not I’m being treated at a hospital, I do want to be treated by a clinician.”

Beebe says, though, that in a pandemic situation, the treatment typically is somewhat uniform, so the need for highly trained medical personnel may be reduced.

“The COVID-19 patients were all receiving the same set of treatments,” he says. “So, you can probably get more people involved in a community response that might not have all of the technical training but have some of the training to be able to take care of them. And you can probably train more people on the spot to do that.

“That’s where hospitals can be valuable,” he says. “By providing guidance to the community, versus shutting their doors and trying to accommodate the patients.”

Ed Avis is a freelance writer and frequent Health Facilities Management contributor based in Chicago.