Preparing new spaces for accreditation

When rounding, facilities managers should pay special attention to active construction and newly

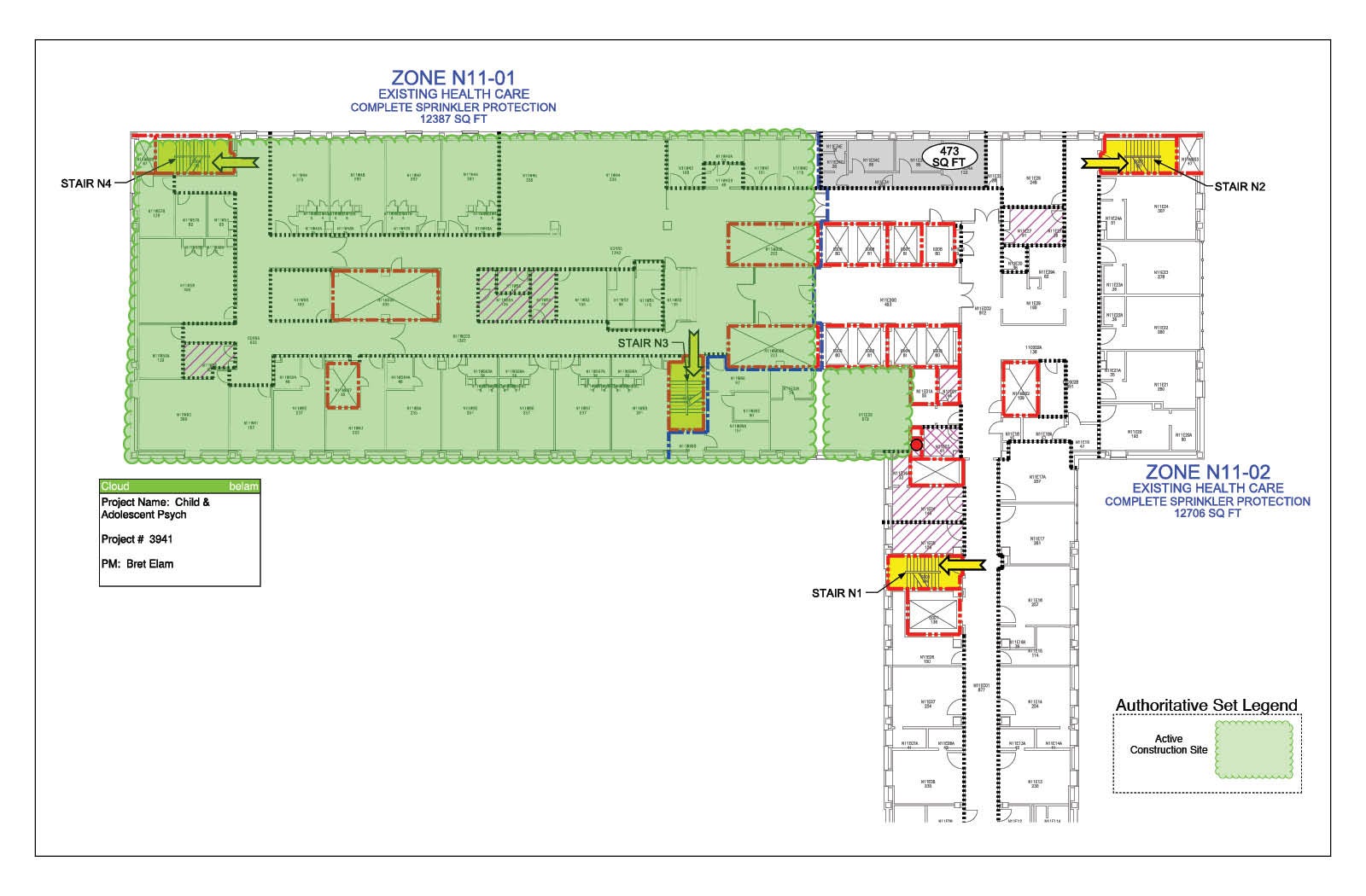

Photo courtesy of University of Maryland Medical system

How do health care facilities managers get a newly constructed space ready for an accreditation survey? The answer is simple: Begin early!

While most regulatory and accreditation agencies (e.g., Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, The Joint Commission, DNV GL and Community Health Accreditation Partner) visit health care institutions a maximum of every three years for reaccreditation, there are many other authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs) that visit more frequently. These include property insurance carriers, fire marshals, building officials, health inspectors, board members and even health care executives, who typically play a role in the construction process.

Getting ready

Health facilities managers and their teams should prepare ahead of time for their inspections and surveys by focusing on the following areas:

Staff education. To have a successful survey, no matter the nature, facilities managers and their teams need to understand the project and its associated regulations. Because construction techniques, products, equipment and regulations are constantly changing, staying current is essential. The best way to arm the team with the appropriate information is through training by using either internal or external educators.

Attending events such as the annual conferences of the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) or National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), accreditation agency training or vendor/consultant-led training can be very effective. Either all team members can attend the training themselves, or designees can attend and share the information with everyone else.

Becoming active members of national organizations like NFPA and ASHE are great ways to stay abreast of construction and regulatory changes. Additionally, membership in these organizations offers regular communication about emerging issues, permits discussion through internet forums, offers access to webinars and provides avenues to request help from industry colleagues.

Regardless of where the education comes from, the key to knowledge absorption is understanding the “why,” not just the “what.” For example, in addition to teaching that every sprinkler head in a ceiling needs an escutcheon (the what), students need to be taught that the escutcheon plays a vital role in containing heat generated below the ceiling, which activates the sprinkler head appropriately (the why).

Additionally, for a new construction project, understanding why the architect specified certain products like wicket doors, also referred to as a door in a door, in the new psychiatric unit (the what) so that patients cannot barricade themselves in a room (the why) are important pieces of information for the team. In this example, it is also prudent to elaborate on all of the hardware specified on the door, such as continuous hinges with chamfered tops, concealed fasteners, security screws, safety glass and anti-ligature door handles, which further reduce risk for this patient population.

Documentation. It is critical for facilities managers to have all of the paperwork and documentation in order. Facilities teams often overlook the details about new projects in the accreditation paperwork. Getting it right early is critical because, many times, it is the first or second activity in the survey process, and it sets the tone for the rest of the survey. If the documents are a mess, the surveyor will assume the physical environment is the same. Conversely, if all the documentation is in order, the surveyor will expect everything else to be in order as well. It is all about the details. Facilities managers should remember: If it is not documented, it didn’t happen.

For new projects, one of the first documentation items is to update the computerized maintenance management system (CMMS). If the project occurs in an existing space, there are elements like fire and smoke dampers, doors, HVAC components, fire alarm devices, medical gas components and even room numbers that will need to be retired in the CMMS database.

Once that is completed, facilities managers should enter the new items into the CMMS and assign asset numbers. A best practice is to request the information from the architect, engineer, contractor and/or vendor. Next, the asset numbers will need to be physically affixed to the item or device. Some institutions include the nomenclature for the asset tags in their guidelines, standards or specifications. ASHE members may access information on “Health Care Facilities Management Data Nomenclature Standards” from the ASHE website at ashe.org/HFDS_sheet.

To reduce the burden on the facilities team, the project plans may assign the responsibility to the construction team. Regardless of who names an item or device, the computer and the field must match. Next, facilities managers must perform a risk assessment for every new item and update the CMMS accordingly. Finally, assigning a preventive maintenance schedule for each item in the database ensures continual readiness.

Physical environment. Surveying the physical environment usually takes the most time in preparation as well as on inspection day, so maintaining focus is important. All the practice and environmental modifications caused by the pandemic forces a renewed focus on the physical environment.

Unlike a formal construction project that is isolated to an area, the pandemic caused modifications all over the building. A common practice is to develop a regular interval for inspection, also known as rounds.

When rounding, facilities managers should pay special attention to active construction and newly constructed spaces. For smaller buildings, they should survey the entire building at once; for larger buildings, they should divide the building into manageable sections. For a large hospital, for instance, a rounding schedule that visits all of the public areas quarterly, all of the in-patient units semiannually and all of the mechanical spaces annually makes inspecting the building manageable.

Regardless of the size of the building, rounding should involve a multidisciplinary team, including but not limited to representatives from facilities, environmental services, clinical/biomedical engineering, safety, infection control and nursing. Additionally, opening every door ensures a thorough inspection.

The most successful rounding programs utilize a checklist. All of the national organizations and accrediting agencies offer checklists, and most of them are free. An important aspect of rounding is having a process for correcting issues and deficiencies. Tools that can be used to correct these include email, spreadsheets, CMMS and digital rounding software. Regardless of the tool used, tracking the completion of the deficiency is the important piece.

When rounding, facilities managers should not neglect above the ceiling. Most AHJs have a newfound interest in all aspects of compliance above the ceiling. Of course, there are compliance concerns about fire and smoke barrier penetrations above the ceiling, but there are also concerns about items on sprinkler lines, fireproofing on structural members, open junction boxes, labeling of medical gases and sprinkler coverage in interstitial spaces containing combustibles. While compliance above the entire ceiling is important, focusing on locations at or near smoke barriers, fire barriers and building separations should take priority. In the event of a fire, deficient barriers can lead to significant personal or property loss.

Facilities managers should have a designated survey route that is developed during survey planning and audited during internal mock audits. ASHE developed a “Survey Guide for Internal Mock Audits” to assist facilities managers during a survey, which can be accessed by ASHE members at ashe.org/surveyguide. This building tour guidance document will help facilities managers to prepare for accreditation surveys.

Survey day playbook. Like football teams, health care teams need to practice for their game day, also known as the day of the survey. Practice includes developing a roster, evaluating the team, testing the offense, establishing the defense, calling plays and defining special teams.

Developing a roster means identifying the players, including those on the bench. Defining the second-string players is important because it enables the team to win even if a key player is absent on survey day due to vacation, illness or for another reason. Roster questions include: Who is going to be the escort? Who is the scribe? Who is scouting the areas ahead? Who is managing the equipment such as the portable high-efficiency particulate absorbing filter tents, drawings, ladders and flashlights? Who is on special teams? Who is the public address announcer? Then, engaging the established team in a scrimmage, otherwise known as an unannounced mock survey, fosters the evaluation. Using in-house evaluators or hiring consultants can accomplish this.

Testing the offense and establishing the defense should occur during mock inspections. Ways to test the offense include evaluating staff response to issues such as what to do for a fire alarm; comparing policies and procedures to observations in the physical environment; and evaluating temperature, pressure and humidity logs. Establishing the defense involves having responses to abnormalities in the documentation such as the addition or deletion of a smoke detector on the inventory or providing interim life safety measure documentation for life safety deficiencies.

Another defensive maneuver during the tour is to show the inspector a recently completed space. This accomplishes a couple of things. First, it allows the inspector to see the investment the institution is making in the care environment. Second, it offers an opportunity for the organization to show compliance with new regulations. Both items permit additional discussion with the surveyor. Facilities managers should be proud of the new spaces!

The escort is like the quarterback. This person calls the plays and is in direct communication with both the referee, otherwise known as the surveyor, and their teammates. The position is critical to the success of the survey. The escort must quickly gain trust, earn respect and develop a rapport with the surveyor. The escort has the ability to call an audible when the surveyor unexpectedly asks to visit a certain location of the health care environment. When this occurs, the escort should consider the path to the audible location and take the surveyor through areas that have frequent or regular rounding.

Defining special teams delineates who is going to provide a supportive role on survey day. Special teams include those who are preparing for the above-ceiling inspections, those who will provide requested reports, those who perform required tasks such as fire drills or generator testing, those with intimate knowledge of specialty spaces like hyperbaric chambers or laboratories, and regulatory experts. While these teams may not have direct interaction with the surveyor, their speed, responsiveness and performance have a direct impact on the outcome of the survey.

Lastly is identifying the public address announcer. This person’s duties sometimes include an overhead announcement like, “our institution welcomes …” but, for the most part, this person’s role is strictly internal communication. For example, as soon as a surveyor arrives, the announcer should send an all-team communication via text, email or other mass notification stating that a surveyor is on-site. Then, throughout the day, the announcer sends messages regarding where the surveyor is going. Finally, at the end of the day, the announcer sends out a summary that contains information about the areas visited, what the surveyor appreciated, the issues that the surveyor found, and any themes and plans for the next day.

Striving for perfection

There is a lot of strategy involved in the survey process, especially as it relates to new construction. While no program is perfect, striving for perfection is expected by a hospital’s regulatory partners and, more importantly, by its patients.

Reviewing facility documents

When reviewing documents, it is critical to ensure that all policies, procedures, and drawing and action plans are up to date. At a regular interval — annually, semiannually or monthly — facilities managers should review departmental policies and procedures for accuracy.

Most of these documents do not change much at each interval, but items that stick out to surveyors include a lengthy duration from the last revision, incorrect regulation citations, and discrepancies between the drawings and the field. These types of issues cause the surveyor to question when the last time the document was reviewed and whether the document captures actual practice.

In addition, reviewing the life safety drawings at regular intervals is a best practice. Constant renovations occur in the health care physical environment to change use, update technology and for expansion, so ensuring that the drawings match the environment is important. If a space is under renovation, a simple notation on the life safety drawings stating this fact and referencing the construction drawings is an easy way to ensure accurate drawings.

A perfect program does not exist, so regular self-assessments are necessary. For example, when on rounds, facilities managers should bring the drawings to ensure what is seen in the field is represented on the drawings. If something is different, they should note it and perform research after the rounds are over. This does two things: the self-assessment identifies issues before inspectors discover them, and self-identification of issues allows the development of action plans for repair or correction.

Being caught off guard with an issue and forced to fix or correct it in an unreasonable amount of time is the worst feeling. If the assessment identifies a life safety issue, facilities managers should be sure to complete an interim life safety measure. If acquiring funds to correct issues is a problem in the organization, facilities managers should cite the regulations. This tends to get the attention of the decision-makers.

Richie Stever, CHFM, CLSS-HC, LEED AP, is vice president of real estate and property management for the University of Maryland Medical System in Linthicum, Md. He can be reached at rstever@umm.edu.