An evolution in oncology design

The atrium in The Harold M. and Eugenia S. Thomas Comprehensive Care Center, located at Bethesda North Hospital in Cincinnati, serves as the connective tissue for diagnostic and clinical destinations in the facility’s platform-based design.

Image courtesy of GBBN Architects

The oncology landscape ranges from subspecialty to multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary models. This landscape is shifting as the care spectrum expands to include diagnostic screenings, symptom management, palliative care and survivorship.

Managing this evolution takes more than co-locating services. Services such as urgent care, imaging, lab, genetics, nutrition and behavioral health are joining the usual program elements of clinics, infusion and radiation oncology. Supportive components like pharmacy, social services and financial counseling take on an expanded and decentralized role to prioritize convenient access and patient empowerment.

In addition, flexibility needs to be incorporated to allow for evolving treatment protocols (including telehealth) and shifts in reimbursements. With the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention forecasting that cancer cases will grow by 20% over the next decade in large part due to the aging population, it’s time to think differently about how oncology spaces can promote a spectrum of care from prevention and treatment to survivorship services.

Whichever model a health care organization chooses, comprehensive services need a platform to house them. This overview highlights how a building can support a transdisciplinary model and leverage partnerships outside oncology like plastics, pain management/palliative, pulmonology, endocrinology, cardiology, neurology, psychiatry, rheumatology and infectious disease. However, the platform concept is scalable for other models, too.

Silos to platforms

A platform-based cancer program accommodates a transdisciplinary model as well as a care continuum for patients. Understanding how this is different from co-locating services in an ambulatory setting involves understanding the quantum leap from multidisciplinary to transdisciplinary care. Oncological multidisciplinary care typically involves a medical oncologist, radiation oncologist and surgeon. While this is a trending model, it does not integrate specialties outside of oncology that are an important part of caring for the whole patient. Comprehensive care involves transitioning to a transdisciplinary model. The challenge lies in how well an organization can dissolve silos and create a seamless, interactive experience. Operations and delivery-of-care strategies play a part in this, but so does the building itself.

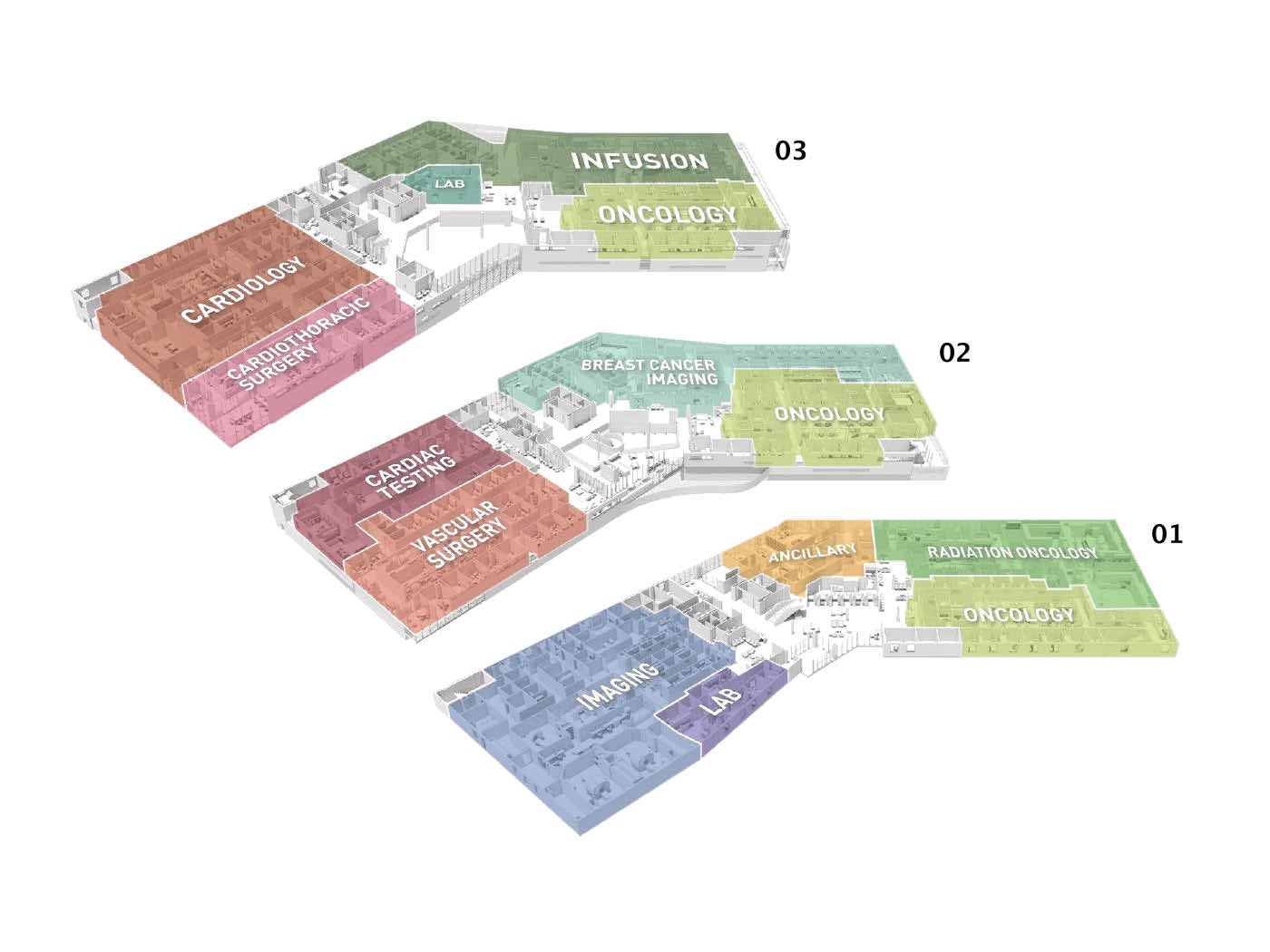

The universal clinic modules at the Thomas Center host a variety of oncology specialties and support transdisciplinary work with cardio-oncology, pulmonary, rheumatology endocrinology and gastroenterology, which have access to an infusion center, radiation oncology, imaging and a lab.

Illustration by GBBN Architects

The platform-based facility includes a universal clinic module; diagnostic and treatment components such as infusion, lab, imaging, radiation oncology, pharmacy, ancillary services; and possibly oncology urgent care. These components support the work of all disciplines using the platform. This model also maximizes space utilization. Scheduling other disciplines into the space when oncology clinics are not running allows hospital systems to drive utilization rates higher. Synergies can be planned for multidisciplinary days when, for example, a rheumatologist’s schedule might include a walk to a module hosting medical oncology for a transdisciplinary visit with a particular patient.

The primary component of platform-based care is a universal clinic layout with consistent patient-facing elements and collaborative features. These modules can be used interchangeably by various disciplines, enabling outside referrals to take place within the oncology facility. The platform allows any type of clinic to operate within all or part of a module. The module can consist of an easily divisible 12 exam rooms and a central clinical work area. This supports clinical teams as they work collaboratively and individually, while accommodating ancillary staff or physicians from other disciplines. Huddle space is included to allow a clinical team to review the cases for the day and devise a care strategy. Consult rooms allow enrollment in clinical trials, pharmacy consults, or meetings with navigators or social workers in a convenient location.

The transdisciplinary setting

Research by GBBN Architects indicates one of the biggest frustrations staff face involves clinical workspace. Teams of clinicians must collaborate, often in a stressful work environment that fails to acknowledge this reality. Clinical observations bear this out: Most movement is clinicians locating one another to coordinate care handoffs; and, too often, specialists and support services are isolated into “found” spaces instead of leveraging their insights by co-locating them with other clinicians.

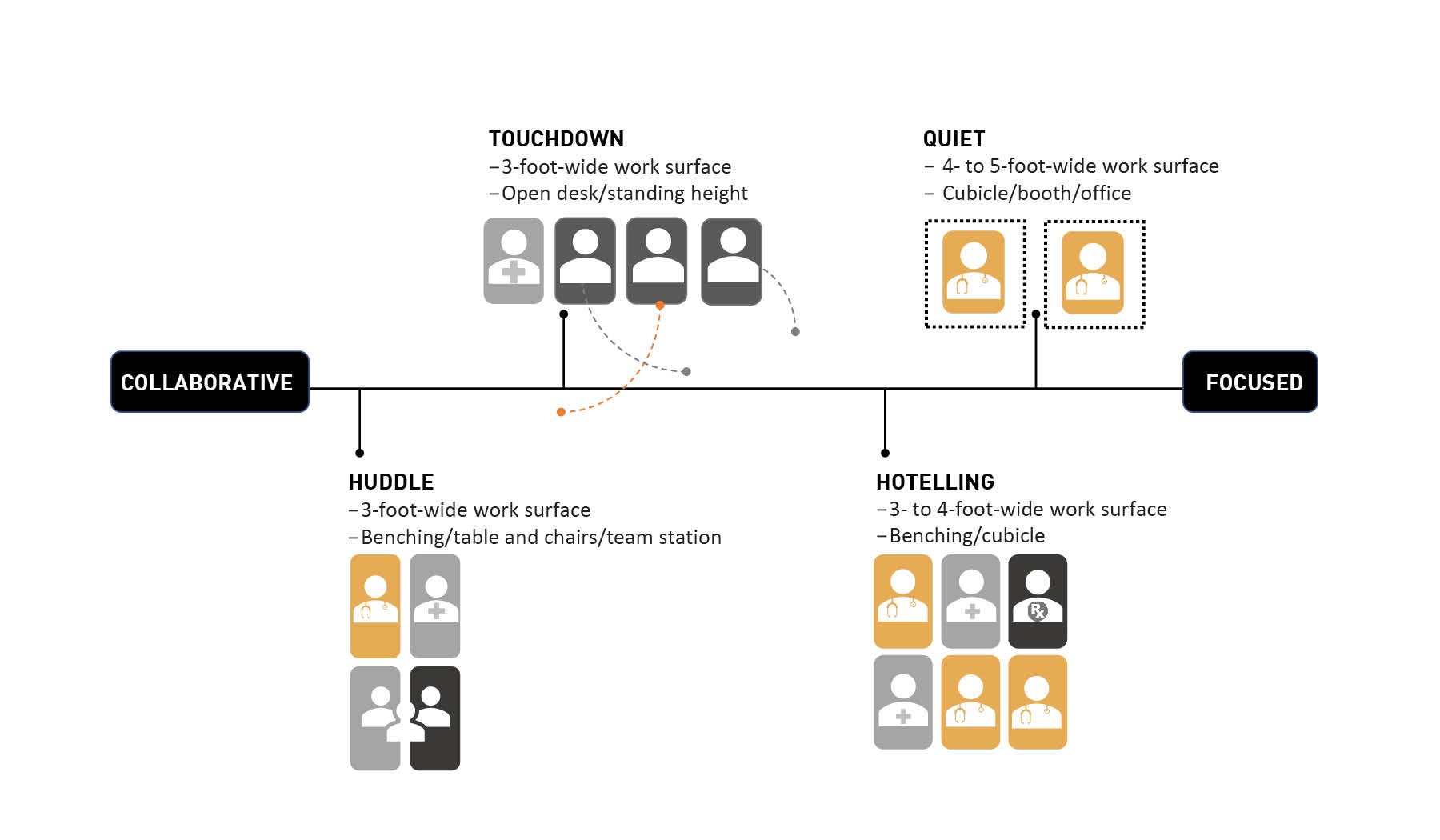

The heightened need for collaboration in a transdisciplinary setting emphasizes the need for connectivity and workspace that accommodates tasks performed instead of clinician roles. A hallmark of this setting is its fluidity — instead of staff working at an assigned spot, they move to zones within the workspace that support their current task.

Designers should look specifically at co-location of staff, workspace centralization to exam rooms, and the amount of team-based, interdisciplinary and independent work that takes place. This informs the types and number of workspaces provided and allows all clinicians to use the spaces most conducive to their current task, whether it’s focused on individual work or a team huddle. Implementing this requires an organizational culture that neutralizes the need to feel territorial about space.

Supportive workspace also includes a restorative component. Oncology is a particularly stressful service line. Patients are seen frequently over an extended time frame, and clinicians become invested in their journey. A routine appointment may quickly pivot to an emergency infusion or even hospitalization. In this demanding care environment, staff easily become depleted and suffer burnout.

Spaces of respite that offer privacy allow staff to compose themselves and rest after a difficult moment. These can be in the form of indoor haven rooms or outdoor spaces. What’s important is that they be within the clinic so they function as a just-in-time resource. A supportive network of colleagues can be fostered through break rooms that promote relaxation, outdoor staff-only space and programs such as yoga classes that build resiliency.

Access and experience

A health care organization’s space sets the tone for its program. According to the Advisory Board research organization, patient experience is emerging as the biggest differentiator among oncology programs. As market competition increases, putting patients at ease in a welcoming, empowering environment reduces stress, improves engagement with care and increases the likelihood to continue with a survivorship program post-treatment. There are several strategies that enhance the patient experience while also helping to improve outcomes. They include the following:

While passing through gardens and encountering the Thomas Center’s natural palette of stone and terra cotta, patients experience an instinctive, biophilic connection to their surroundings.

Photo by Brad Feinknopf

Convenience and a seamless experience. Patients — especially those with comorbidities — value these characteristics. Being able to schedule a multidisciplinary appointment affords the patient a chance to see multiple specialists in the same exam room over an extended visit.

The patient has the reassurance that these specialists are collaborating with one another in real time as they each perform examinations. This ensures that the care plan recommended is comprehensive, not myopic to whatever specialist is being seen that day, leading to fewer delays and care handoffs.

Being able to have all appointments — even those with specialists outside of the oncology department — within the same familiar setting also increases the likelihood the patient will make and keep those appointments. If other diagnostics are determined to be needed, they can often be scheduled immediately after the visit, again reducing delays in care.

Some strategies to accomplish this include infusion chair-side scheduling and concierge services featuring patient coordinators who can schedule and field medical questions and concerns. Because oncology patients need more than clinical resources, platform-based care considers ancillary services and makes them patient facing, arraying a wealth of resources before the patient to ensure they get the support they need.

GBBN Architects’ primary research on clinical workspace indicates a central work core in each clinic maximizes staff visibility and accessibility to their patients and each other. Collaboration is fostered through zoning that promotes task-based work.

Illustration by GBBN Architects

Amenities that make sense. Most architects, health systems and service line managers get giddy imagining a well-appointed patient resource center with brochures, computer workstations, lounge areas, a wig shop and education rooms. The truth is that many of these rather large footprints go unused. Patients and their loved ones prefer to use their own handheld technology. They do not want to sit in a makeshift library or shop the limited selection of prosthetics or wigs when they have the internet at their disposal for sourcing these items.

Instead, nonclinical spaces should be thought of as the connective tissue for the platform destinations. For every element the designer plans, they should ask, “What else could this be?” Having multiple functions in a space provides the flexibility to offer a wider range of programs, including survivorship engagement. A café is a great way for a loved one to do research while enjoying a cup of coffee. This same space can be used for patient education sessions and incorporate a teaching kitchen for learning about diet modifications. A dedicated chapel is often not discoverable and, when somebody does wander in only to find someone else sitting there, it’s not likely they want to break their solitude.

On the other hand, a quiet corner with individual pockets of space partially open to a lobby provides that place of solace and refuge — and it can also be used for a meditation class. The same goes for waiting rooms. While it is advantageous to have some seating near the entry to a clinic, such spaces should be seen as part of the connective tissue, not the clinic module. Opening these spaces up to the rest of the building can encourage patients or loved ones to explore the facility, enhancing their experience while helping them to discover and take advantage of some of the other amenities.

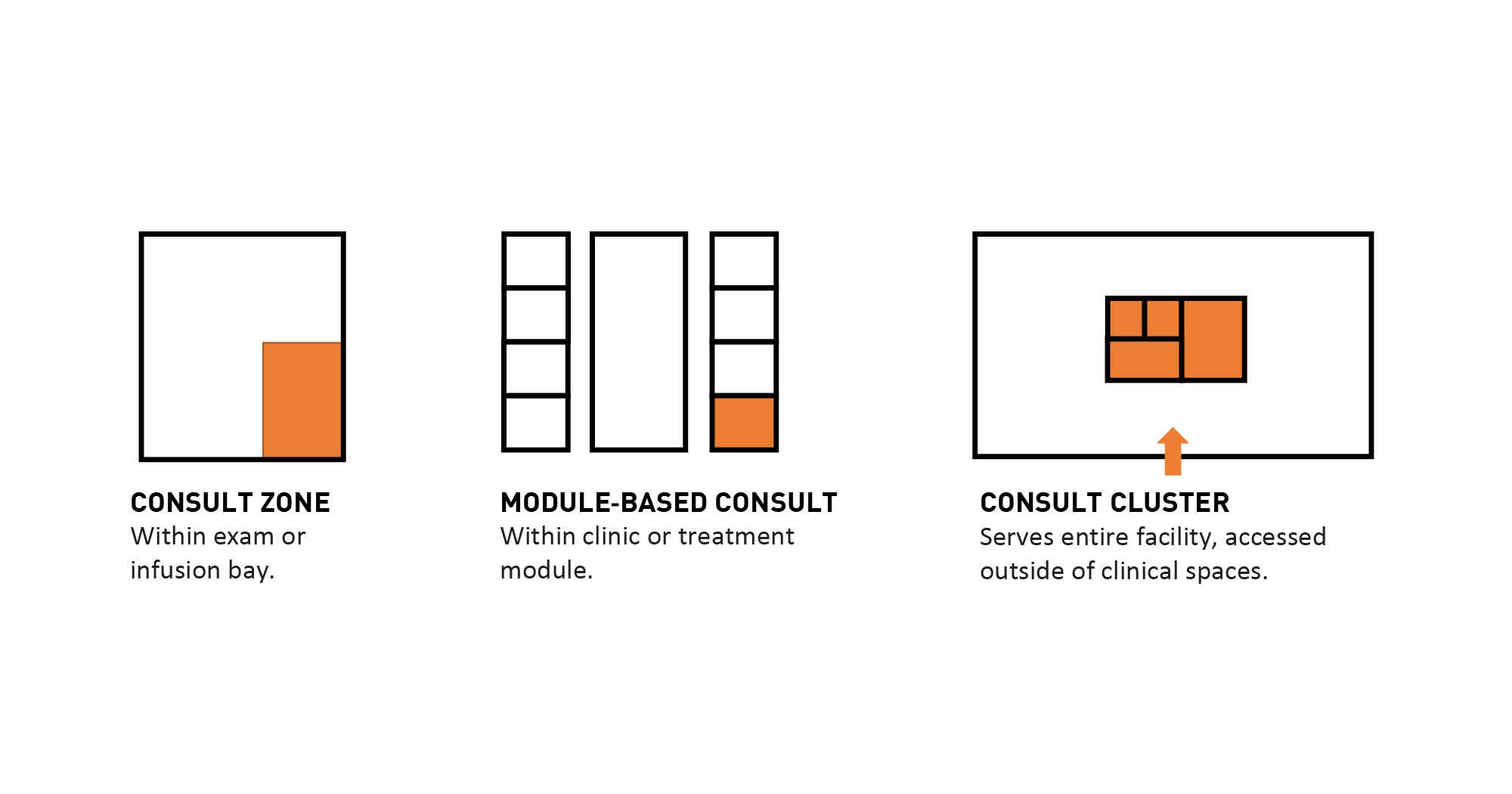

Bringing services to patients. Aside from the obvious things like co-location of services, platform-based care elevates the role of the consult room. Consult rooms are among the most misunderstood and poorly leveraged spaces in ambulatory care. In fact, they usually get converted to an exam room or someone’s office.

A transdisciplinary strategy will necessitate taking full advantage of consultation space. If this is new to an organization, it might find staff has the tendency to keep patients in the exam room for their entire visit. Organizations should operationalize the right fit and sequence for moving patients out of the exam room and into space more conducive to learning or meeting by having a consult room strategy.

Designers should consider addressing the consult function as three distinct types of space. The first is site of care — a consult zone within an exam room or infusion bay to allow quick meetings with ancillary services, such as pharmacy, or to discuss the care plan after an exam. Next, clinic-adjacent spaces are larger rooms that can hold up to eight people and are used for longer nonclinical interfaces, such as nurse navigator appointments or enrollment in clinical trials. Finally, main level consult rooms can vary in size, but some larger ones that can accommodate an entire family should be in the mix. These rooms are convenient to the point of entry and support visits with ancillary services that do not involve a clinic visit, such as a nutritionist, social worker or geneticist appointment.

Zones within an exam or infusion bay (left) allow care conversations in a way that help the patient feel empowered, while those adjacent to clinical or treatment modules (center) provide breakout space for nonclinical events and consult clusters (right) provide for larger group meetings.

Illustration by GBBN Architects

Oncology urgent care is another component of the platform to consider. Designers should think of it as a modified access point within the system that will provide increased flexibility and security for patients. This is an important way to effectively help patients manage symptoms instead of subjecting them to a battery of diagnostics and infection risks if they present at the emergency department.

A robust telehealth interface also should be built into the platform to accommodate the increased use of oral chemotherapies and home-based care. Fewer patients may be arriving for in-person visits, and growth in volume of patients in the program should be accommodated via remote care that relies on the ability to capture vitals via remote monitoring.

Platform-based care

Oncology’s evolution relies on operational shifts as well rethinking how clinical, amenity and staff spaces are designed. More clinicians will be involved in treatment, and more staff touch points for wraparound services will be needed.

This accumulation must be considered in terms of radical process and culture change. Anything that creates a bottleneck for the patient or an added layer of difficulty must be rethought. Holistic care matters more than ever, and comprehensive services must be seamless and integrated with one another across the care continuum.

Platform-based care offers an infrastructure to accommodate this evolution, including incorporating transdisciplinary care. The platform building blocks comprise universal clinic modules, diagnostic and treatment services, urgent care, telehealth, and a range of consult spaces and amenities that provide respite and address nonclinical needs for patients, families and staff.

Flexibility and adaptability across the platform is one of its hallmarks and supports this rapidly growing and constantly changing service line.

Angela Mazzi, FAIA, FACHA, EDAC, is principal at GBBN Architects and 2021 president of the American College of Healthcare Architects. She can be reached at amazzi@gbbn.com.