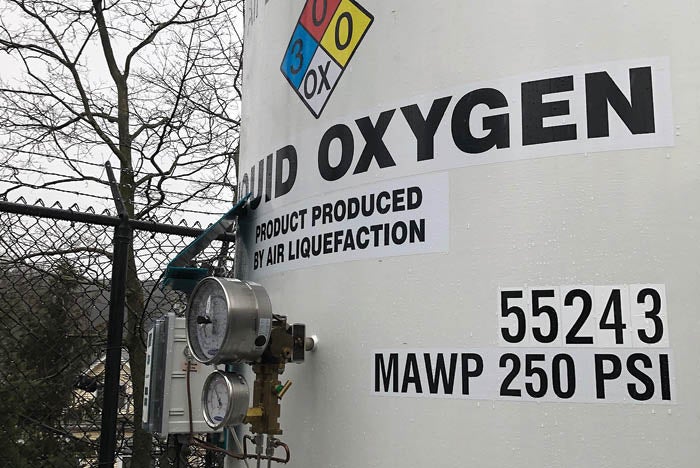

Ensuring med-gas system reliability

Medical gases are essential for proper patient care and reliability of these systems is critical to patient safety.

Image courtesy of Acute Medical Gas Services Inc.

It is more important than ever to think about how professionals reinvent health facility management programs to help ensure critical utility systems are reliable even when faced with unpredictable situations.

The COVID-19 pandemic has taught that the disciplined and meticulous operation of medical gas and vacuum systems in health care facilities is paramount to ensuring these systems remain safe and reliable for patients who may be depending on them for their survival.

In the 2021 edition of the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, operational management of these systems continues to be one of the major focal points.

While the new edition may not be accepted in all jurisdictions for some time, a look at the requirements can provide a model for medical gas system operational management going forward.

RFAs and PTWs

In the May edition of Health Facilities Management magazine, Jonathan R. Hart, PE, SASHE, CHC, technical lead for fire protection engineering at NFPA, introduced two new concepts included in the new edition.

The operational management section for piped medical gas and vacuum systems (PMGV) now includes requirements for a designated responsible facility authority (RFA) and a permit-to-work (PTW) system for these infrastructures. The intent is to further refine existing policies and procedures and provide guidance on how to manage these important utility systems in the health care environment.

A discussion of each of these two new concepts follows:

Defining the RFA position. NFPA 99 has used the term “responsible facility authority” for many years with regard to system testing and documentation requirements. Both the 2012 and 2018 editions state that testing reports must be submitted to the RFA and that the RFA is responsible for ensuring that, before initial use of medical gas and vacuum systems, those systems have been adequately tested, and the test results demonstrate the systems are acceptable for patient use.

However, until the upcoming 2021 edition, there has not been a definition of an RFA nor any guidance provided on how to implement such a practice. The 2021 edition provides this guidance and will go a long way to help better explain how the RFA fits into the larger picture of the operational management of these critical life-supporting systems.

The 2021 edition will require each health care facility to designate one or more individuals as the RFA. The RFA is the accountable party for these systems and is responsible for ensuring the medical gas systems are continuously safe for patient use. This includes oversight of any work tasks that are conducted on these systems, including installation or modification of systems and inspection, testing and maintenance (ITM), or repair tasks on existing systems.

Prior to isolating medical gas systems, a risk assessment and PTW system should be used for proper planning during shutdowns.

Image courtesy of Acute Medical Gas Services Inc.

The designated RFA has the primary responsibility for implementing the code requirements for the PMGV systems for the facility. The operational management of these systems includes conducting risk assessments, interpreting compliance requirements, and writing and upkeep of the facility’s medical gas management programs, policies, standard operating procedures and emergency management program.

The RFA is also tasked with developing and enforcing a PTW system, evaluating and accepting ITM reports, supervising personnel training and licensing programs, as well as oversight and maintenance of critical records and documentation. The new PTW system should act as the documented processes, procedures and methods used for this oversight. (More specifics of a PTW system are discussed later in this article.)

Risk assessments are regularly conducted to determine any potential impacts on both patient care and safety. This includes when conducting interim life safety measures or other compliance obligations for clinical spaces and the physical environment that are required for the proper management of the facility. These assessments should be conducted with the support of other departments as needed, but the RFA should take the lead when it pertains to the medical gas systems.

Another important role for the RFA is interpreting applicable codes, standards and compliance requirements. This can be an art form, but at the very least it requires sound knowledge of the regulatory requirements and ability to assess risks and hazards to mitigate their potential impacts on patient care. These both help ensure the required body of knowledge and expertise is at the table when having these discussions.

Responsible oversight and reliable medical gas systems are required for proper patient care.

Image courtesy of Acute Medical Gas Services Inc.

One of the most important requirements for an RFA is the writing and upkeep of the facility’s operational management programs, emergency management plans, and other policies and procedures regarding the PMGV systems, including the development and enforcement of the PTW system.

Well-managed PMGV systems are essential to patient safety. An unplanned failure of a hospital’s oxygen system could have a catastrophic effect on routine patient care. Ongoing operational and ITM requirements for these systems are necessary for ensuring they are functioning properly and supervised continuously.

The duties of the RFA are varied and diverse in nature. Therefore, there is an expectation that they be technically competent and qualified, and that the selected individual(s) can demonstrate that competency through appropriate qualifications. The code provides some options for demonstrating competencies and qualifications that a capable RFA could possess. The person(s) designated as the RFA shall in all cases have appropriate knowledge and technical understanding of the specific equipment installed at the facility, as well as a broad understanding of the design and compliance requirements for these systems.

It should be noted that it may not be practical for one person to manage all of the tasks discussed here, especially in larger facilities. If multiple individuals are involved in these functional responsibilities, they must be clearly designated, and their roles and responsibilities should be addressed within the management program.

The direction provided in the 2021 edition of NFPA 99 allows for some flexibility in the operational structure for these policies and procedures. The RFA may or may not be responsible for day-to-day operation of the medical gas systems and may designate others to share those responsibilities.

Resources

In large facilities that have multiple maintenance shifts and defined roles for task completion, this is a likely scenario. In smaller facilities, it may be the same person who oversees the program, and it is very possible that outside vendors may perform some of the tasks required at the request of the RFA. In either case, there should be at least one individual that has ultimate responsibility for the medical gas systems in operation at the facility. For example, while the RFA has ultimate responsibility for these systems, the individual at a hospital who is best suited to properly evaluate and accept ITM reports might not be the RFA, but instead a qualified maintenance technician.

The management of records and documentation might also be better handled at an administrative level rather than with the RFA. Nothing is meant in the new requirements to eliminate the ability of an organization to place responsibilities with those individuals best qualified and that have the best technical competencies for such work.

In fact, it is quite the opposite, and the approach is meant to be flexible for the organizational needs with regard to oversight. However, clear roles and expectations that are well documented will assist in meeting these requirements and are a must for a successful program.

Formalizing a PTW system. The “permit-to-work” system is meant to formalize and codify a policy approach to managing routine work, such as maintenance, repair and construction activities, as they relate to the PMGV systems.

Temporary medical gas systems, which have become the norm during the current pandemic, must ensure patient safety during their use.

Image courtesy of Acute Medical Gas Services Inc.

The PTW system should include developing and enforcing applicable procedures to ensure the uninterrupted quality and continuity of supply of these systems. The procedures should also address appropriate communications, alternative supply or adjustments in patient care arrangements, competency of those who work on the PMGV systems, shutdown and restoration procedures, safety procedures and testing of PMGV systems.

The process that comes to mind as a good comparison to the intent of the PTW system is a typical confined space entry permit program. In a confined space permit system, there are multiple layers of review prior to an individual entering into the space. The review includes a clear scope of work definition, duration of entry, chain of command and communication protocols, a method for a clear acceptance of the plan and a signoff by all involved.

There is also significant monitoring during the entry (i.e., air quality monitoring) and a safety protocol developed to get people out in an emergency as well as a confirmation of the closeout of work and validation of the safety and well-being of all those operating under the permit. This analogy helps to better understand some of the similar complexities involved in working on the oxygen system at a hospital.

Because the level of risk in performing some tasks on PMGV systems are far less than others, it seems counterintuitive to have a one-size-fits-all approach to the permit system. Developing a risk-based criteria to determine the various levels of work that should be included in the PTW system is necessary to assure that the proper levels are included in the system.

For example, low-hazard permits based on a low-risk task could have a less restrictive process to determine staff involvement and approvals, and therefore could generally be issued fairly quickly. However, a high-hazard permit may require a more involved review and assessment by multiple departments, involving clinical, respiratory and facility management staff for assistance in the planning and execution of the work with final authorizations coming from the executive level of the hospital. A high-hazard permit should be used anytime there is a chance for system contamination or cross connections, the use of purging and/or brazing operations, a requirement for third-party testing to be performed, an isolation of a source of supply that is actively serving patient areas, or emergency repairs.

High-hazard work will generally require testing by a third-party verifier. Prior to system use, the permit process should include a verification by both the third-party agency and the RFA that all inspections and testing have been completed successfully, system integrity has been achieved or maintained, and the systems are ready for patient use as required by code. There also should be a process to address emergency work. If an emergency requires immediate approval to proceed with work, there should be means to allow for an emergency permit to be authorized quickly by the RFA or their designee to ensure any required emergency operations can be dealt with in a timely manner.

Periodic operational checks help to ensure medical gas systems continue to function properly and are safe for patient use.

Image courtesy of Acute Medical Gas Services Inc.

While the majority of tasks will be easy to assess whether they are low- or high-risk, some tasks will need to be evaluated via a risk assessment, such as the isolation of a supply source (i.e., an individual medical air compressor or vacuum pump) from the rest of the system for maintenance or repair. This may or may not be considered high-hazard work.

For example, the design standard in NFPA 99 is that a minimum of two compressors (supply sources) are required for a medical air central supply system. One compressor is the primary, and the other is a fully redundant backup. If this backup is isolated during maintenance, the anticipated system redundancy has been eliminated. Thus, if the primary source fails while the backup is isolated, the hospital may lose its supply of medical air, and the risk of this situation occurring should be considered during the review. However, if the system has more than two compressors, this may not be as significant a concern and could be considered low-hazard work because isolating a single compressor will not totally eliminate the redundancy within the system.

Regardless, procedures should be developed for a risk-based assessment of tasks so the facility can ensure a continuous supply during maintenance in the event of system failure.

Low-hazard permits should be used for routine tasks that do not require complicated planning or staff notification and are unlikely to disrupt patient care. This might include isolation of a portion of the system that is not currently being used for patient care to perform a like-for-like replacement of a broken component. This would not require a third-party certification, and as long as the repair work and functional testing is completed by someone who is technically competent, there should be no reason to consider this high-hazard work.

Use of low-hazard permits shouldn’t be required for typical maintenance rounds or system “observations” since they do not have an effect on the operation of the systems.

An essential utility

Reliable medical gas and vacuum systems are an essential utility and provide critical sources of life-supporting gases that are required for proper treatment of patients in the health care environment.

While the 2021 edition of NFPA 99 may not be adopted in all jurisdictions for a while, these new RFA and PTW requirements were developed with the goal of ensuring these systems remain safe and dependable on an ongoing basis.

Undoubtedly, the 2021 edition of NFPA 99 continues to provide guidance toward this goal and confirms the understanding that responsibility improves reliability in the operational management of these critical systems.

Jonathan C. Willardt, CHC, PMP, CMGV, is the president and CEO of Acute Medical Gas Services Inc., Goffstown, N.H. He is a principal member of the technical committee on medical gas and vacuum piping systems, which is responsible for the applicable sections of NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, and a principal member of the technical committee on industrial and medical gases, which is responsible for the NFPA 55, Compressed Gases and Cryogenic Fluids Code. He can be reached at jon@acutemedgas.com. This article provides a general description of regulatory actions and does not constitute legal advice.