Health care villages and districts create caring communities

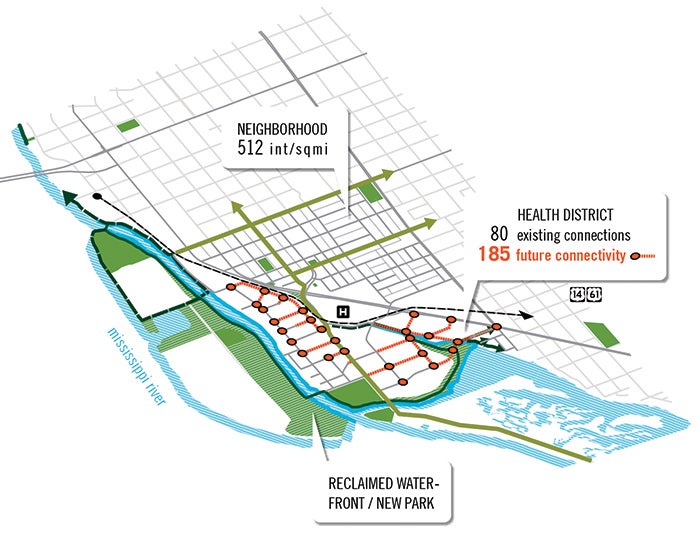

An “outside-in” perspective that integrates health services more fully into the community can be seen in the Baton Rouge (La.) Health District. Rendering courtesy of Perkins+Will, Illustration ©Hartness Vision

As hospitals and health systems develop strategic facility plans for the future of care, many are following the edict attributed to architect Daniel Burnham: Make no little plans. Health care providers are working with architects, urban planners, developers and governmental bodies to create medically oriented, mixed-use developments that extend the borders of the traditional medical campus.

Anchored by health care facilities, these communities encompass elements like housing, retail, education, research and development, recreation, culture, social services, public transportation and active transportation in an environment designed to promote health and wellness.

Like integrated medical care, in which specialists work collaboratively for the good of an individual patient, an integrated health district is a comprehensive, cooperative approach to facility planning and population health management.

Ramanathan Raju, M.D., FACS, FACHE, says that in the past, a health system would determine a need for care in a certain location, create a facility and consider its duty to the community fulfilled. “We felt our obligation was over, because we provided health care and people needed to come,” he says. But if it takes three buses to get to a building, or the area isn’t safe for pedestrians or doesn’t offer other services, people won’t come, he notes. In planning a health care access point, systems “should take into consideration other factors to make it more effective,” Raju says. “We cannot deliver health care anymore in isolation.”

‘Health care, not sick care’

Raju served until recently as president and CEO of NYC Health + Hospitals, the health system that operates public hospitals, clinics and post-acute, long-term care facilities in New York City. NYC Health + Hospitals, the New York City Economic Development Corp. (NYCEDC) and the borough of Staten Island are working together to create a mixed-used health development said to be the first publicly planned and funded project of its type. Plans for the Sea View Healthy Community include medical, retail, residential and community facilities, as well as open space, in an effort to improve area residents’ access to physical activity, healthy foods, social engagement and healthy environments.

“Medical campuses in the past have been developed around people who are sick. This is a campus to make sure people stay healthy,” says Raju. “That is where health care in this country is moving. It’s about health care, not sick care.”

The mixed-use community will be established on approximately 180 acres of buildable land on the former Sea View Hospital campus. Sea View Hospital opened in 1913 to treat tuberculosis patients. “At that time, there was no known cure for tuberculosis. All they knew was that fresh air, sunshine, nutritious diet and a little bit of physical exercise all had therapeutic effects. You can really see that reflected in the architecture of the buildings and of the campus,” says Munro Johnson, vice president, development department, NYCEDC.

NYC Health + Hospitals, NYCEDC and the office of Staten Island Borough President James Oddo worked with design firm Perkins+Will to develop a vision plan for the site that incorporates housing and environmental design elements, along with health-related programs, to create a holistic healthy community. At press time, NYCEDC was planning to issue a Request for Expressions of Interest to solicit development proposals aligned with the vision plan.

According to Johnson, the team initially “assumed that [the site’s] future development would follow the usual pattern of a traditional medical campus, with an emphasis on typical health care facilities.” However, analysis revealed little need for a typical health facility in this part of New York City. Chronic noncommunicable diseases like heart disease, diabetes and cancer, which are associated with people’s living environments and the lifestyles those environments foster, are the major health concerns in neighborhoods near the Sea View campus.

Clockwise from left: The planned Sea View Healthy Community in Staten Island, N.Y., will include original structures from the historic Sea View Hospital campus which opened in 1913 as a tuberculosis treatment center and later fell into disuse. The site will incorporate housing and environmental design elements, along with health-related programs, to create a holistic healthy community.

Johnson says the team determined that “the best health care facility we could deliver to this part of Staten Island is a healthy community, because it is physical activity, access to nature, access to fresh and healthy food and social interaction that best address the diseases that are the most responsible for mortality and morbidity in this area.” In many ways, he notes, the site is coming full circle to the early days of tuberculosis care.

To promote physical activity, active transportation will be a key factor in the design of the Sea View community. “We’re looking at street design that promotes walking and bicycling around the campus,” Johnson says. The team is planning proximities in the mixed-use development around a five-minute walking radius, which is generally accepted as the amount of time people will walk, rather than drive, to reach a destination. “Having the grocery store or pharmacy within walking distance of where you live is something we can design into this plan,” says Johnson. “The design is oriented around making the healthy choice the easy choice.”

For increased access to healthy food, planners are looking at bringing back the community farm and gardens that were maintained at the old Sea View Hospital. A green grocer, farm-to-table restaurants and farmers markets also may be included in the development.

The site is immediately adjacent to the Staten Island Greenbelt, which comprises 2,800 acres of interconnected parks and open spaces. Johnson says the team wants to establish connections that allow people to access the park system directly from Sea View.

NYC Health + Hospitals currently operates a nursing home on the Sea View campus; a portion of the other building space on-site is made available to community service and arts organizations like Meals on Wheels and the Staten Island Ballet. For the past decade, NYC Health + Hospitals’ systemwide facility management plan has been to reduce the footprint for inpatient care and put resulting empty building space “to good use for the community,” Raju explains. Sea View Healthy Community “is consistent with our philosophy, but takes it to a different level,” he says.

For residents of the existing nursing home and the additional housing for seniors and developmentally disabled people planned for the community, social services and cultural programming on campus will provide opportunities for social interaction. Design features meant to encourage socializing, like plazas and a library, are under consideration, Johnson says. “We are focused on diminishing social isolation and ensuring that residents have space for healthy activity, to develop friendships and also have a medical presence to manage chronic disease,” says Raju.

Medical and wellness facilities for primary care and diagnostics will support the healthful design and programming of the community. Additional medical and research facilities are planned for future phases as the legacy of Sea View continues in a new way. Research conducted there in the 1950s ultimately led to the discovery of a widespread cure for tuberculosis. “We see a real opportunity, as the public health legacy at Sea View is renewed, for it to again become a destination for health and wellness,” Johnson says.

‘Outside-in’ design

By encouraging health care providers to think outside the hospital box and coordinate efforts with other municipal stakeholders, health districts can serve both as places that support healthful living and mechanisms for improved community health.

Jason Harper, AIA, LEED AP, senior medical planner in the New York office of Perkins+Will, says, “Medical campuses are typically designed from the inside out.”

“If you think about a hospital, there’s a lot of good stuff in there,” adds Basak Alkan, AICP, LEED AP BD+C, senior urban designer in the firm’s Atlanta office. “There’s a pharmacy, gift shop, lots of retail, lots of action. But everything’s inside and connected by corridors. She says a new, “outside-in” perspective that integrates health services more fully into the community is “what needs to be done for health facilities today, with today’s mandates on population health.”

The Baton Rouge (La.) Health District is an example of this type of thinking. Development of the district originated with the Baton Rouge Area Foundation, a South Louisiana philanthropic organization that is partnering on the project with local residents and a dozen major health care organizations. The health district, which incorporated as a nonprofit organization this year, includes regional medical centers, clinics, academic and research centers, and a health insurance provider among its members.

The master plan for the district was initiated to address severe congestion issues along a corridor of Baton Rouge where many health care institutions are located. “As the community looked at its medical district, it saw these regionally renowned health care facilities and a terrible environment around them,” says Alkan, who worked on the Perkins+Will master plan. Traffic problems created inefficiencies and an unhealthy environment for the thousands of people who live, work and receive care in the area; staff members from one hospital were literally driving across the street to get to restaurants because they didn’t feel safe walking, Alkan reports. “The lack of coordination on anything that falls outside a hospital’s doors was negatively impacting the health care business and growth of that district, which otherwise provided excellent care,” she says.

A partnership between Gundersen Health System and the city of La Crosse, Wis., has developed a plan that proposes a mixed-use infill project between the hospital and the neighborhood that will give hospital staff nearby housing options and support neighborhood revitalization efforts.

Among the master plan’s key recommendations is the implementation of a transportation and land-use plan to build the district’s street network; enable people to walk, bike and use mass transit; connect to parks and open spaces; and promote balanced, diverse and orderly development in the district. In addition, the master plan proposes the creation of a four-year medical school in Baton Rouge, as well as the establishment of a Diabetes and Obesity Center to provide centralized services for addressing these major public health issues.

District members are jointly funding the nonprofit developed to implement the master plan. The nonprofit group worked with city agencies to generate some public funding for infrastructure improvements. “They are partnering on healthy placemaking,” Alkan says. “It’s really beginning to change the face of the district.”

Similar partnership was shown between Gundersen Health System and the city of La Crosse, Wis., in the development of a joint master plan for the health system’s La Crosse hospital campus and the adjacent Powell-Hood-Hamilton neighborhood. The plan proposes a mixed-use infill project between the hospital and the neighborhood that will give hospital staff nearby housing options and support neighborhood revitalization efforts. In addition, the plan offers a structure for the sustainable redevelopment of a nearby industrial waterfront to give patients, staff and residents better access to recreational opportunities along the Mississippi River.

Health care design “can either encourage the life of the community or deaden the life of the community,” Harper says. “There’s a choice to be made that involves a broader sort of programmatic thinking.”

Customers of the future

On projects across the country, hospitals and health systems are choosing to engage with their communities to broaden the scope of campus planning, redesign the interface between health facilities and neighboring areas, and better serve health care needs. In Cleveland, the MetroHealth System is in the midst of a major transformation plan designed to modernize campus facilities and encourage local economic development and healthy lifestyles. In Chattanooga, Tenn., the new Children’s Hospital at Erlanger is intended to serve as a gateway to a downtown Wellness and Innovation District.

Shannon Kraus, FAIA, FACHA, LEED AP, principal and Washington, D.C., office director for HKS Inc., says that on projects like these, communities are serving more as partners than simply in their conventional role as review boards. Facility design projects used to end at the hospital property line, but with increased pressure on health systems to prevent unnecessary admissions and readmissions, “there’s more dialogue, more conversation about what the community needs.” Kraus says. A more complete understanding of and response to community needs can serve both the health care mission and bottom line of a hospital, by helping to use resources more efficiently and improve patient satisfaction, he notes.

Charleston, S.C., health system Roper St. Francis worked with local county leaders to develop guiding principles for the design of the Roper St. Francis Berkeley Hospital and health village in Goose Creek, S.C. The first phase of the project will involve the construction of a medical office building and adjoining hospital that initially will have 50 beds. Subsequent phases will concern development farther from the campus core, with a focus on integrating the campus into the community and meeting changing health care needs, explains Neal Corbett, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP, project executive and vice president in the Atlanta office of HDR Inc. While project team members are keeping their eyes open regarding specific design elements with an emphasis on flexibility, these may include retail, healthy eating or fitness components, Corbett says. As the hospital planning team notes, “Our customers today are sick people — our customers in the future will be well people.”

Amy Eagle is a freelance journalist based in Homewood, Ill., who specializes in health care-related topics. She is a regular contributer to Health Facilities Management.