Hospitals become more energy efficient, but power usage remains flat

Acute care hospitals that fail to cut energy use are almost assured of paying higher utility costs as the number of power-guzzling medical and administrative devices continues to grow.

Today’s sophisticated imaging equipment, especially in the operating room; the transition to electronic health record systems; and energy-intensive data centers are major contributors to growing electricity use, says Dan Doyle, chairman, Grumman/Butkus Associates, an energy consulting and engineering firm in Evanston, Ill.

The problem is compounded by the fact that the use of more electronic devices generates more heat and an increased cooling load, he adds.

“All of those devices and equipment add up and they use a lot more electricity,” Doyle warns. “If you stand still in terms of energy reduction, your bills will keep getting worse.”

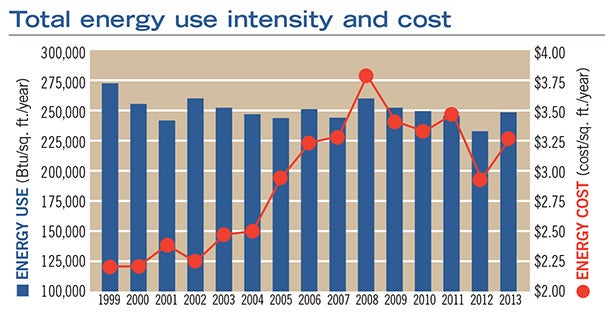

A 2014 benchmarking survey by Grumman/Butkus of about 100 Midwestern acute care hospitals, which was released this year and based on 2013 energy data, shows that total energy costs, including electricity, natural gas and steam, rose almost continuously from about $2.25 per sq. ft. per year in 1999 to a peak of about $3.75 in 2008. Costs dropped to $3.00 in 2012 before rising again to $3.25 in 2013.

During the same period, total energy use declined from nearly 275,000 British thermal units (Btu) per sq. ft. a year in 1999 to just under 250,000 Btu, where it hovered from 2000 to 2013.

The price of electricity has driven most of the increase in overall energy costs even though electricity use has remained nearly steady from 1999 through 2013, according to the survey. Electricity costs rose off and on from 6 cents per kilowatt-hour (Kwh) in 1999 to a peak of about 7.7 cents per Kwh in 2008. It has remained at or just below that level through 2013.

The plummeting cost of natural gas since 2008 has helped to offset electricity costs. From nearly 40 cents a therm in 1999, prices rose to a peak of about 95 cents per therm in 2008 before steadily dropping to slightly higher than 50 cents per therm in 2013. At the same time, natural gas use has declined from about 180,000 Btu per sq. ft. per year in 1999 to just under 150,000 Btu per sq. ft. per year in 2013.

Fortunately, there are numerous opportunities to get ahead of the energy-consumption game, but it takes time, Doyle says.

|

| SOURCE: GRUMMAN/BUTKUS ASSOCIATES The chart shows trends in energy use and total energy costs for electricity, natural gas and steam from 1999 through 2013. |

”You just have to be very vigilant. There is no home run that you hit out of the park. You just keep hitting lots of singles and grinding away,” he says.

Retrofitting lights, installing high-efficiency motors and variable-frequency drives, and fine-tuning the HVAC system and building controls are in that time-proven category.

Doyle says that Grumman/Butkus has conducted retrocommissionings at about 30 hospitals in the Chicago area and each has averaged about $120,000 in energy savings the first year with about a six-month payback.

He also says that hospitals need to consult with their local utility company to find out if it offers financial assistance for any energy-efficiency investments, and especially for more costly moves like installing new high-efficiency chillers.

He cited the example of one Midwestern hospital that replaced three older chillers with more efficient units that cut the facility’s energy bill by more than $100,000 annually. The units use nonozone-depleting refrigerants, another benefit of the upgrade, which was financed in part with local utility rebates.

One possibly missed opportunity for hospitals is borrowing from their endowment funds to pay for energy conservation, Doyle says. Endowments might typically earn about 5 to 8 percent a year in interest, while a bundle of energy-conservation measures with a six-year payback or less can generate a minimum 16 percent annual return on investment.

Hospitals can choose to move half of the savings back into the endowment and the other half into a green revolving fund for future energy investments. “It’s a no-brainer,” he says.