Water quality standard for sterile processing

Poor water quality can negatively affect processing equipment as well as instruments used for surgeries and other medical procedures.

Image by Getty Images

Health care sterile processing is indispensable by providing safe and sterile instruments for all types of patient treatments and procedures. This is primarily through sterile processing departments (SPDs), which utilize water to ensure proper washing, disinfection and sterilization of medical instruments.

The publication of American National Standards Institute (ANSI)/Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation® (AAMI) ST108:2023, Guidance for Water Quality, resulted from industry and health care professional consensus on water quality specifications necessary to maintain safe and cost-effective sterile processing, according to the document. This new standard, which was released last year, has notable implications for health care facilities managers and other leaders as well as facility water management plans. ANSI/AAMI ST108 provides health care teams with a way to ensure that water does not become a limiting factor for SPDs and surgical services’ daily operations.

Notable implications

Many hospitals have their own SPDs. However, this is not always the case, and some may serve as a hub for local or regional distribution to other sister hospitals, which may lack a SPD of their own. Cost estimates range up to $1 million over the first year of disruption for a 110-bed facility that provides 5,000 operative procedures per year and experiences steam quality issues that require taking the SPD offline, according to the article “When Sterile Processing Goes Down: An Economic Analysis of Alternative Strategies for Supporting the Service,” in the August 2017 issue of Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology.

Poor water quality can negatively affect processing equipment and instruments used for surgeries and other medical procedures, such as endoscopes. Different water quality parameters are needed depending on any combination of the processing steps, equipment and/or the disinfectant being applied. Improper water quality can lead to (but is not limited to) incomplete cleaning, rusting, staining or water hardness stain buildup on both instruments and equipment, according to the articles “Code Grey: stained surgical instruments and their impact on one Canadian Health Authority,” in the third 2017 edition of Healthcare Quarterly, and “Finishing of Stainless Steel, and Why It May Still Corrode,” in the November 2023 issue of Finishing & Coating.

Additionally, mineral contaminants in water and/or steam can result in staining of liners used inside rigid sterilization containers and instrument blue tray wrap. These types of stains typically lead to rejection by perioperative teams, and the instrument is then returned to the SPD for reprocessing.

Combined, these issues may result in stained instruments or linens that cause a newly opened kit to be rejected at the surgical suite, unplanned and costly maintenance, replacement of instruments, additional manpower in the form of hand cleaning, shutting down the department due to emergency shutdowns (e.g., a municipal water supplier issues a boil water alert) or failed survey investigations, according to the article “Emergency Preparedness: Strategies for Maintaining Water Supply Quality and Access for Sterile Processing,” in the August 2023 issue of AORN Journal.

So, how is the facilities team engaged in this area? While ANSI/AAMI ST108 focuses on the SPD, SPD personnel are not building water system and treatment experts. This is where the facilities team plays a vital role and can contribute to the success of water quality in these areas.

Facilities teams are involved in the process, from the boilers producing steam used in sterilizers to the central plant supplying feedwater to washers to the high-purity water generation systems often used for final risk.

Foundational knowledge

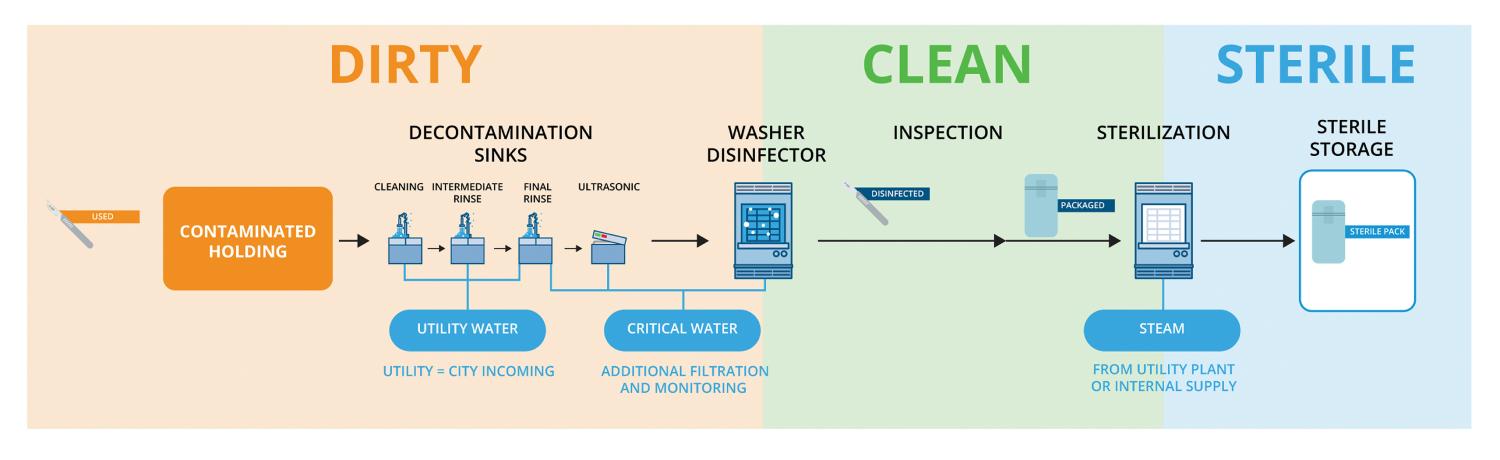

Some foundational knowledge can help provide a baseline of water in sterile processing and the processing steps. Specifically, SPDs are separated into “dirty,” “clean” and “sterile” sections, which follows the flow of the entire process.

The three types of water quality as defined by ANSI/AAMI ST108 include:

Utility water. This is typically used during initial rinsing to eliminate larger contaminants, often simply tap water from the municipal source or with minimal processing that does not meet high-purity standards. Instruments may undergo a series of succeeding sinks, which rinse for increasingly smaller particles. Final rinses with critical water will follow; however, it requires special attention.

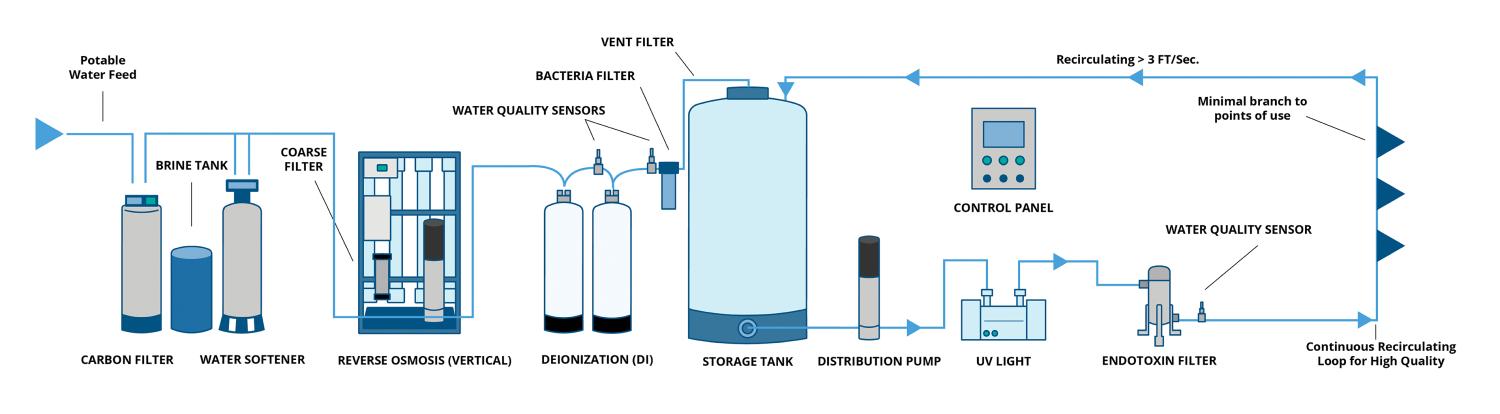

Critical water. This is water that meets high-purity requirements. Its generation is an involved process, requiring multiple layers of processing to achieve the appropriate water quality, including higher levels of filtration, such as reverse osmosis and deionization. Critical water is used in more delicate rinsing, such as ultrasonic and washer-disinfectors that typically divide the dirty and clean side, in which instruments come out of the clean side ready for a final inspection and packaging for sterilization.

Steam. This is the final type of water, which is used to sterilize packs of instruments after passing through every other step and inspection. Sterilized packs are labeled and stored in the sterile room to be delivered where needed. The steam source may be supplied from a central utility plant piped to the department or via an internally generated supply from some equipment. Clean steam can even be generated from critical water in some specific cases.

TIRs versus standards

Since 1967, AAMI has published consensus-based standards. AAMI produces two main types of technical documents: technical information reports (TIRs) and standards. Both types of documents share the same goal: “to enhance the safety and efficacy of the use and management of medical devices and health technologies.”

Although TIRs and standards are both developed by a committee and performance based, they also have significant differences. TIRs, for instance, have limited scopes, are not reviewed publicly, focus on guidelines and may be interim documents while a standard is developed. Standards, on the other hand, are comprehensive, subject to public review, establish requirements and are ANSI accredited.

A TIR is intended to address an emerging approach or technology to put much-needed information into the public space as an intermediate step before becoming a standard. To become a standard requires a more formal and rigorous development process.

The publication of an AAMI standard indicates that consensus knowledge has matured enough to establish requirements that represent best practices rather than general guidelines. Two important factors of AAMI standards include:

- They generally don’t focus on design specifications as they can limit the development of new technologies.

- They are voluntary; however, they represent industry best practices and are increasingly seen as benchmarks for authorities having jurisdiction, such as The Joint Commission.

Key highlights

It is impossible to give full coverage of the 102-page ANSI/AAMI ST108 guidance document or a full picture of AAMI’s TIR34, Water for the reprocessing of medical devices, which proceeded it. However, there are important updates that health care facilities managers should be aware of regardless of their prior knowledge of TIR34:

Roles and responsibilities. A significant update from AAMI TIR34 was the expansion of the role of a multidisciplinary team responsible for water quality and the facility water management program (WMP). They include:

- Executive sponsorship (someone with authority to make decisions).

- Facilities personnel/health care engineers.

- An infection preventionist.

- An SPD representative.

- A clinical engineering/biomedical representative.

- A perioperative services representative.

- A water treatment specialist.

- Third-party vendors, as needed (e.g., water safety/treatment specialist, sterilizer manufacturer technical support and scientists).

While there are many stakeholders, facilities managers and SPD personnel naturally are the primary responsible parties from the WMP.

According to ANSI/AAMI ST108, facilities personnel are responsible for water system installation, qualification and routine validation of water quality and water system maintenance, and SPD personnel are responsible for monitoring processing equipment and devices, which may include other areas of the facility beyond the SPD, such as endoscopy, dental clinics or other specialty suites.

The shared responsibility of the program ensures that resources and responsibilities (e.g., time, budget and manpower) are divided and that multiple expert viewpoints are considered when making data-driven decisions.

Risk analysis. This section covers the effects that water impurities can have on medical device processing and remains largely intact from AAMI TIR34, with the inclusion of the following excerpt: “As part of the water management program, monitoring water quality is a prospective process meant to confirm that control strategies are functioning as expected. Monitoring is performed in order to detect when control strategies might require review or remedial action.”

This wording reinforces that effective monitoring is an essential part of the WMP for sterile processing. In addition, Section 5 makes references to The Joint Commission’s water management standard EC.02.05.02 as a cross-reference to this rationale.

Water quality specifications. ANSI/AAMI ST108 is not about water treatment but quality specifications. While water treatment plays a vital role (e.g., critical water generation), ANSI/AAMI ST108 does not advocate nor inherently necessitate the purchase of new water treatment equipment to meet these requirements. A multi-disciplinary team should always discuss and review data available to them (or find relevant data) before making an investment in additional equipment.

There are several tables (including on steam) that a water management team (WMT) must understand. They include:

- Table 2: Categories and performance qualification levels of water quality, including additional parameters tested during exceptional events such as start-up of new systems, major repairs and shutdowns, or other circumstances that require additional testing (e.g., a boil water notice for a municipality).

- Table 4: Water quality monitoring requirements, including routine testing during ongoing operations.

- Table 5: Water quality monitoring requirements for generation or origin.

- Table 6: Water quality monitoring requirements for point-of-use.

Tables 5 and 6 deserve special attention, as they focus on monitoring activities of the WMP with emphasis on location and frequency. A literal reading of these sections may result in a premature evaluation that ANSI/AAMI ST108 requires hundreds of regular tests. This is not the case.

Section 5 on risk management is clear that the program needs to be evaluated by the WMT to decide what is best for the program by asking proactive questions, such as what is manageable, sustainable and will provide the right amount of data to make informed decisions.

Water treatment systems installation and operation qualification. It is vital to assess the current state of equipment that is involved in treating potable water and steam used to supply the SPD.

Of note, ANSI/AAMI ST108 does not specify what equipment is required to obtain the correct level of water quality. Rather, the WMT needs to conduct a risk analysis that uses test results of water, equipment and frequency of potential issues, like discoloration of liners or instruments, observed or reported to the SPD to determine if new equipment is needed to purify the water.

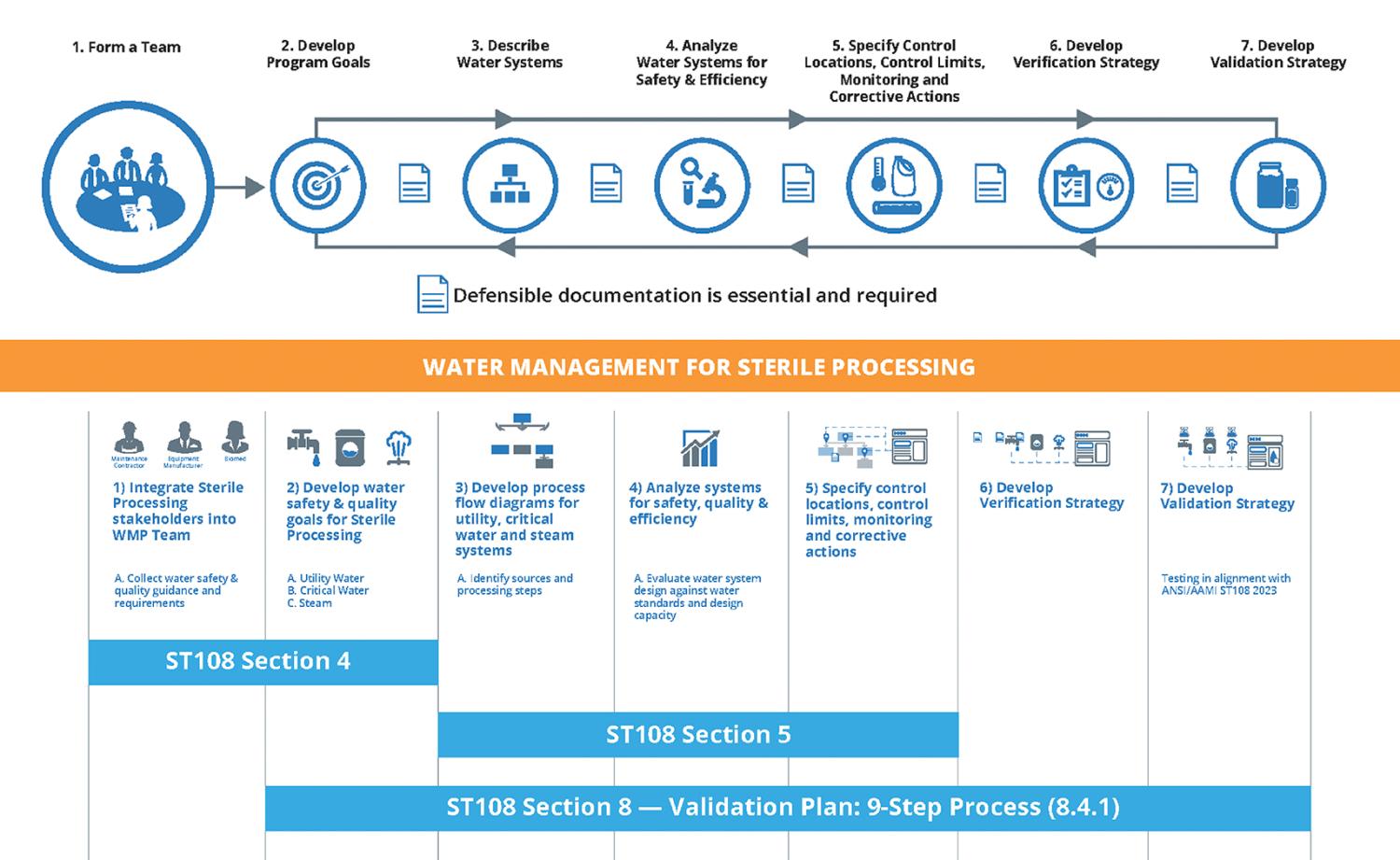

There is quite a bit in this section related to water treatment systems and associated qualification. However, particularly noteworthy is the subsection titled “8.4.1 Validation Plan.” The validation plan provides a nine-step process to guide the WMT.

A key contributor

Most, if not all, hospitals should have an existing WMP at some level. As such, the inclusion of an SPD into these existing programs is one that is both logical and operational, given the overlap between water management stakeholders that already exists within a program aligned with ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188, Legionellosis: Risk Management for Building Water Systems.

The seven steps of WMPs, as defined by ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188, have been the industry standard framework for water management since 2015. Overlaying ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188 with the key sections of ANSI/AAMI ST108 shows a strong parallel between these two standards. While focused on SPD-specific considerations, the overall approach remains analog to what should already be performed through ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 188.

The role and expertise of facilities managers is an integral part of the WMT that cannot be understated. Facilities professionals should proactively invite their SPD colleagues to their WMT’s next water management meeting to discuss how best sterile processing might integrate and contribute to the grander WMP.

Across departments, many sterile processing managers and personnel are still coming on board to ANSI/AAMI ST108 and will require assistance and education on water quality and treatment that only a facilities manager can provide. ANSI/AAMI ST108 is an opportunity to cement water management as a key driver for health care system success, with facilities management being a key contributor.

Erika Wilson, BME, is regional manager at Phigenics LLC in Warrenville, Ill.; Jill E. Holdsworth, MS, CIC, FAPIC, NREMT, CRCST, CHL, is manager of the infection prevention department at Emory University Hospital Midtown in Atlanta; and

Russell N. Olmsted, MPH, CIC, FAPIC, is director of infection prevention and control at Trinity Health in Livonia, Mich. They can be reached at ewilson@phigenics.com, jill.holdsworth@emoryhealthcare.org and olmstedr@trinity-health.org.