Hospital building project requires resourcefulness

Hackensack University Medical Center’s Helena Theurer Pavilion was under construction during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Image copyright Jonathan Hillyer

Even during the best of times, building an addition to an active hospital is no simple task. Hackensack University Medical Center’s (HUMC’s) Helena Theurer Pavilion in Hackensack, N.J., is a nine-story, 530,000-square-foot building that was built on a small, congested urban site spanning over an existing busy street and connected to an operational Level 1 trauma center.

The new building included 24 operating rooms (ORs), 72 private prep/post-anesthesia care unit (PACU) rooms, 50 intensive care unit rooms, 25 universal rooms and 150 medical-surgical rooms and was intended to be a transformational project for the hospital and the population it serves.

As if the challenges involved with such a complex endeavor were not enough, the team responsible for the design and construction of the building — RSC Architects, Page Southerland Page, Syska Hennessy Group and Blanchard Turner Joint Venture LLC — were also facing a global pandemic.

Construction, which began in September 2019, was progressing on time and within budget, and structural steel erection was underway when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. HUMC became the epicenter of the crisis in northern New Jersey, and the county executive put a halt to all construction. Fortunately, New Jersey’s governor decreed that hospital construction was essential, and work was allowed to continue without significant delay, but the project team would need to pivot to accommodate this new reality.

It was an enormous undertaking and a success story that serves as a model for future-proofing hospital planning, design and construction projects.

Learning in a crisis

While steel erection was beginning, the pandemic started to grow. In response to the overwhelming number of COVID-19 patients at the hospital during the early days of the pandemic, hospital facility plant operations responded by turning standard patient rooms into ad hoc negative pressure rooms. They also converted the hospital’s existing cafeteria into a COVID-19 ward to help treat the surge of patients.

Private prep and recovery rooms along with a flexible heating, ventilating and air conditioning design allow the entire prep/post-anesthesia care unit area to become negative pressure.

Image copyright Jonathan Hillyer

Designed and constructed in only seven days, this cafeteria-turned-COVID-19 unit included 72 beds for patients. The conversion, in combination with other emergency projects across the campus, expanded the hospital’s patient capacity by 23% and helped HUMC meet the demands of this unprecedented event.

Although the cafeteria already employed a “one-pass” air-supply system that prevented the recirculation of exhaust, the team had to take additional safety measures, including adding HEPA filters to the exhaust system, which vented all the air from the newly converted COVID-19 unit directly to the building’s exterior. To supplement the existing system and attain the necessary negative isolation for the space, fan-powered HEPA filter units were added and ducted directly to the exterior through existing windows.

The plan was for the cafeteria to act like airborne infection isolation (AII) rooms, which have been standard since the days when tuberculosis spread easily. But, in most cases, the percentage of AII rooms in hospitals is low. The cafeteria, in contrast, had to serve as one large AII room to isolate the space from the rest of the hospital. Other items that were added to complete the conversion of the cafeteria included medical gases, emergency electrical receptacles and patient monitors at each bed, and nurses stations and hand-washing stations throughout the space.

Information gleaned during this time was invaluable to HUMC’s ability to treat COVID-19 patients and protect its staff from infection. Hospital leadership wanted to capture the benefits of these lessons in the new pavilion and provide the building with the ability to handle any such events in the future.

Applying the knowledge

While the pavilion was still under construction, the project team was asked to take a step back and review the design of the new building to determine how best to make it more adept at handling an airborne contagion like COVID-19.

“Some of the things we learned during the course of the pandemic — things we never would have thought of otherwise — we were able to incorporate into the building’s construction,” says Mark Sparta, president at HUMC and regional president for the northern market at Hackensack Meridian Health.

During the pandemic, HUMC achieved negative pressure in existing patient rooms by removing windows and using portable exhaust fans to vent the rooms to the exterior. This was time-consuming and costly, and required remedial work to get the rooms back to their original condition. The team examined how to allow the hospital to increase the quantity of negative pressure rooms without having to provide the costly temporary measures.

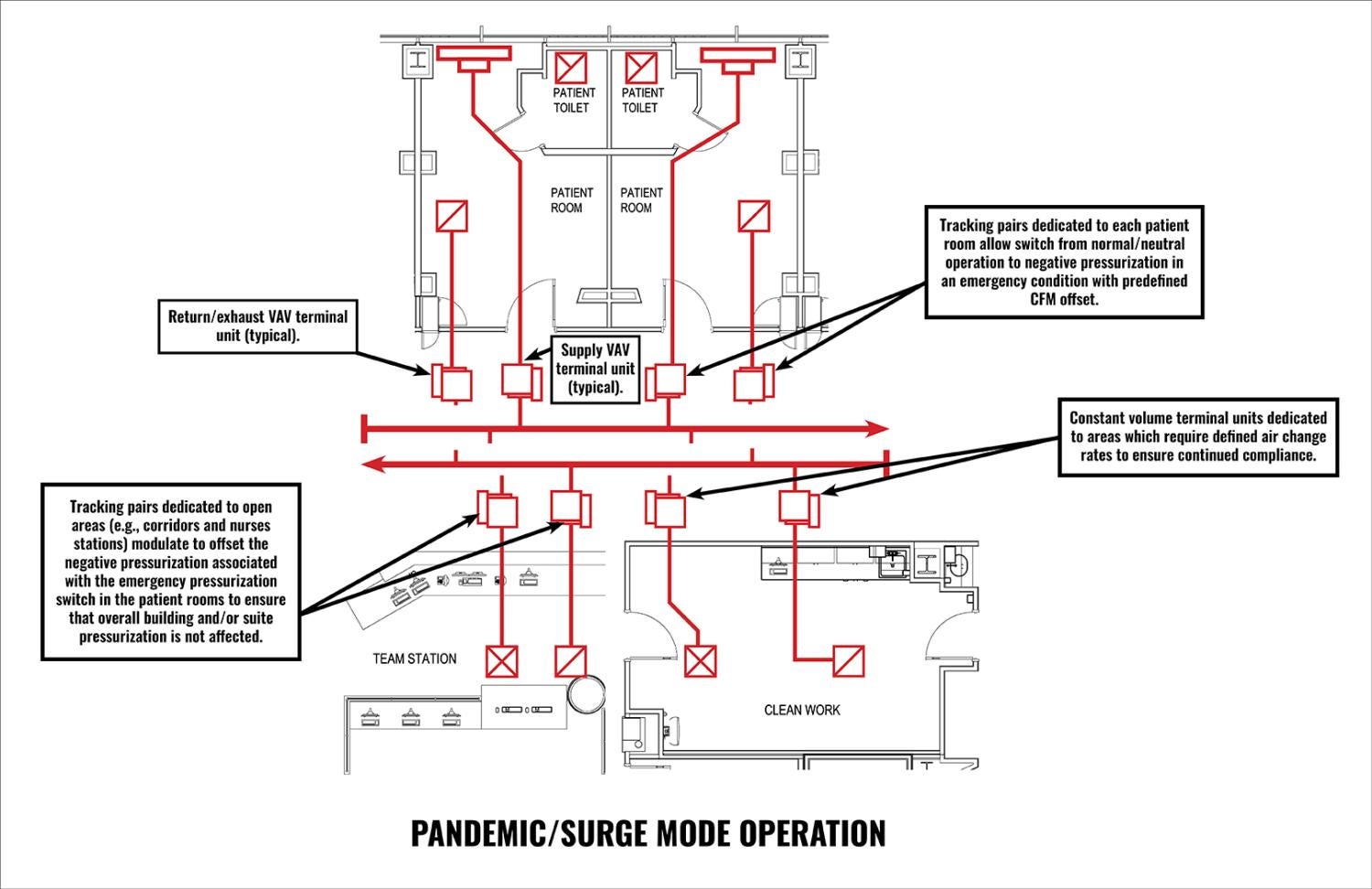

To this end, the design team reviewed the mechanical design of the building, added variable air volume terminal units to the return ductwork for all 225 patient rooms and revised the rooftop air-handling units to have the ability to circulate 100% outside air and accept HEPA filters.

As a result of these changes, HUMC plant operations staff is able to create negative air pressurization in patient rooms on a unit-by-unit basis by utilizing presets within the building management system without the need for any modifications to the mechanical system. This allows containment within the patient space and positive pressure protection in the clinical staff space.

Another priority was minimizing unnecessary interactions between staff and infectious patients, allowing the hospital to conserve the supplies it had available and minimize risk to staff. The team added “pass-throughs” and emergency power outlets outside every patient room. Pass-throughs enable tubes for ventilators and pumps and IV tubing to feed into patient rooms from the adjacent hallway.

Double-sided nurse servers and IV tubing pass-throughs were added to each room to help limit staff from unnecessary exposures.

Image copyright Mauricio Rojas

They accordingly reduce the need to enter patient rooms to maintain these devices. The original design already incorporated nurse servers, which are supply cabinets that can be accessed from both inside and outside patient rooms. Through the nurse servers, staff members can resupply the cabinets from the hallway without entering the patient rooms. Both features — the pass-throughs and the nurse servers — reduce the risk of infection for staff attending to contagious patients.

Furthermore, tablets were installed outside of each patient room that pull information directly from the hospital’s electronic health records system to alert staff and visitors of the patient’s isolation status and safety measures required to enter the room to protect staff from infection.

During the pandemic, the hospital saw a dramatic reduction in the number of elective surgery procedures. This shift in priorities opened other opportunities for the use of the prep/PACU suites adjacent to the ORs. By making mechanical revisions, like those made on the patient floors, the team was able to provide the hospital with the opportunity to use the prep/PACU suite as a triage area or for patient overflow during times of emergency. The prep and recovery rooms, which were designed with flexibility in mind, can be turned into private rooms, and the entire suite can be converted to a negative pressure area if needed to respond to another pandemic.

The Helena Theurer Pavilion incorporated infection control and safety measures throughout its design, including hand-washing stations in the public lobbies of each floor, digital messaging boards alerting the public about current hospital policies and access control to patient floors.

Staff mental health was also a major planning consideration at the beginning of the project. The architects designed large break rooms with daylight and views, quiet respite rooms on the nursing floors and corridors with a lot of natural light. These design features are intended to improve working conditions for staff and allow them moments away from the stresses of their jobs.

Technology was provided in each patient room to allow direct video conferencing between patients and family, and allow for telemedicine and virtual rounding.

Image copyright Mauricio Rojas

Some of the pandemic’s saddest stories involved isolated COVID-19 patients who could not communicate with friends or family members. The patient rooms in the pavilion address this problem by providing a patient experience system that allows them to hold real-time video calls with their families or friends directly from their room.

The system includes a 65-inch television monitor, a built-in camera and a bedside tablet for patient use. Patients can watch television shows or on-demand movies, consume educational material and even order meals through the system. The tablet also allows patients to control the lights, temperature and window shades in their rooms. Additionally, the system can be used by clinical staff to conduct virtual rounds of patients if needed.

Although the speed of the project and the team’s ability to pivot were remarkable, the effects on the project budget were significant. The hospital’s administration understood that this was a chance to build for the future with additional flexibility, which was becoming vital during the pandemic. Upgrades to the building’s heating, ventilating and air conditioning systems alone cost $4 million and pushed up the pavilion’s total project cost. However, even with these changes, the team was able to bring the project within the original budget of $714.2 million due to underruns in other areas.

Supply chain issues and added costs for both materials and labor were significantly impacted by the pandemic. While many of the major construction trades (e.g., structural steel, foundations and curtainwall) and most of the equipment for the mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems had been purchased before the pandemic, other construction materials (e.g., metal studs and insulation paint), medical equipment and stone were subject to significant cost increases. Lead times for these materials also increased, with some suppliers being unable to meet previous delivery commitments.

However, even with all the issues the team experienced during the pandemic, including the redesign of the mechanical systems, the team was still able to complete the pavilion three months ahead of the original project schedule, and HUMC moved into the building in December 2022.

Lessons learned

An important lesson the team learned centers around early collaboration among trades. This project is an example of the interconnection of architecture and engineering, and the coordination required among many different disciplines in modern construction. Early engagement between the design team and trade partners allowed for time savings during construction and a better building at the end of the day.

Another lesson involved education. The project team was fortunate to have a client who understood why a redesign and its impact on budget were unavoidable. But in cases where a client is less knowledgeable about public health and safety, or more stubborn about budget, it is up to the design team to explain the rationale.

Communication throughout a project is also key. The project team included almost 100 people during the height of construction. Every decision during the pandemic-related redesigns had to be reviewed and discussed with all parties, including the hospital, owner’s representatives, design team, construction manager and the trades responsible for completing the work in the field.

This was especially critical during the pandemic. The changes to the building were being made during construction, with COVID-19 safety restrictions impacting the ability to get the work done on site and access to materials affected by supply chain issues. The team’s ability to communicate with each other and the relationships they built over the course of the project allowed them to work through problems and get the work completed.

Perhaps the most vital lesson is flexibility. The COVID-19 pandemic caught many hospitals off guard, and scientists initially could not pinpoint how it was spreading. A future pandemic may look very different, and it’s difficult to predict what safety measures will be required within hospital settings. However, flexible design solutions like those provided in the Helena Theurer Pavilion give hospitals the ability to meet these unforeseen needs.

Making it manageable

Early and advanced preparation for the unexpected requires a great deal of creativity and preplanning, and its associated equipment is probably more expensive than equipment that does not allow for modifications.

However, the investment is worthwhile in the eyes of the design team as well as the hospital.

“Hopefully we don’t see another pandemic for another hundred years,” Sparta says. “But we don’t want the people sitting here a hundred years from now saying they had a chance to create a situation that was manageable, and they didn’t take it.”

RELATED ARTICLE: Protecting a construction team and keeping a project on track

During the COVID-19 pandemic, while most of the news was about patients and staff, keeping essential workers such as contractors safe was also a major priority.

There were several phases of the COVID-19 pandemic as it related to the construction of the Hackensack University Medical Center’s (HUMC’s) Helena Theurer Pavilion in Hackensack, N.J.

When the pandemic started in mid-March 2020, excavation and foundations were the only trades on-site, with a total of 35 workers. These were “outside work” tasks, which made it easier to maintain social distancing and eliminated the precautions that would have been needed in an enclosed building.

As construction progressed, and more trades and manpower were on-site, the construction team had to regularly adapt to maintain a safe working environment. The project peaked at 435 workers on-site, with an average 350 workers daily.

The construction manager instituted numerous precautions, which included:

- Daily temperature screenings by registered nurses.

- Mandatory N95 mask use for all workers.

- Maintaining 6-foot social distancing, including limiting the number of persons allowed on the personnel hoist.

- Locating hand-wash stations on every floor and encouraging workers to wash their hands regularly.

- Staggering start times and break/lunch times to avoid large groups.

- Scheduling work on multiple floors to prevent grouping of workers.

- Cleaning and disinfecting work and break areas twice a day.

- Mandatory vaccinations for workers.

The construction trades knew that the timely completion of the Helena Theurer Pavilion was a way to help the community in a time when many felt helpless. The process was undeniably difficult, but everyone was proud to be involved.

Erik Polyzou, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP BD+C, is project manager at RSC Architects; Thomas Ford, LEED AP, is associate partner at Syska Hennessy Group’s Hamilton, N.J., office; and Donald Ferrell is senior vice president of facilities and construction at Hackensack Meridian Health. They can be reached at epolyzou@rscarchitects.com, tford@syska.com and donald.ferrell@hmhn.org.