Creating an emergency management playbook

Image by Getty Images

It is vital for hospitals and other health care facilities to respond effectively to any type of emergency they may encounter, such as natural disasters, acts of violence, outbreaks of disease, or failures of municipal power or water systems. Moreover, health care facilities face the added challenge of responding to these emergencies while viewing them through an infection prevention lens.

A well-executed emergency plan will mitigate the spread of infection for the duration of the event and through the following recovery period, keeping all patients, visitors and staff safe until normal operations are restored.

To help in this endeavor, the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) recently released the Emergency Management Playbook: A Back-to-Basics Approach to Infection Control and Emergency Management for Health Care Facilities (ashe.org/emergency-management-playbook), from which this article is excerpted and edited.

It was designed to support facilities managers, environmental services (EVS) technicians, incident management teams and others working in all types of health care settings.

Understanding the risks

Learning to recognize infection risks in health care means learning to identify when there is an opportunity for germs to spread and make people sick. To recognize these opportunities, one needs to know where germs live (reservoirs) and how they can get from place to place or to people to cause an infection (pathways).

Reservoirs can be in or on the body, such as on the skin or in the gut, respiratory tract or blood. Reservoirs can also be in the environment, such as on surfaces, in dirt and dust, or on devices. Common pathways include touch, inhalation and splashes and sprays.

Because no two days in health care are ever the same, there will be moments when one might need to apply infection control recommendations to new or unknown situations. Additionally, when an emergency strikes, there are usually other considerations, including:

- Life safety. It is important to strike the right balance between infection control and addressing other life safety issues. For example, quickly evacuating patients and staff in a fire may take priority over maintaining isolation of patients with infectious diseases.

- Compliance. Health care facilities are highly regulated, but in an emergency, it may not be feasible to follow every policy, process and protocol that applies during normal operations.

- Facility standards. Standards for maintenance, sustainability, workload management and other day-to-day operations may need to be altered or suspended when a facility is responding to or recovering from an emergency.

- Systems and infrastructure. Ventilation, electrical, medical gas, wireless networks, phones and water systems may not work as expected during an emergency.

- Community partners. During an emergency, health care facilities often need to work closely with local, state or federal officials, or with administrators of other sites, such as hotels or schools, where health care services are temporarily being provided.

Areas of interplay

The interplay between infection control and other aspects of emergency management are covered in these sections of the Emergency Management Playbook:

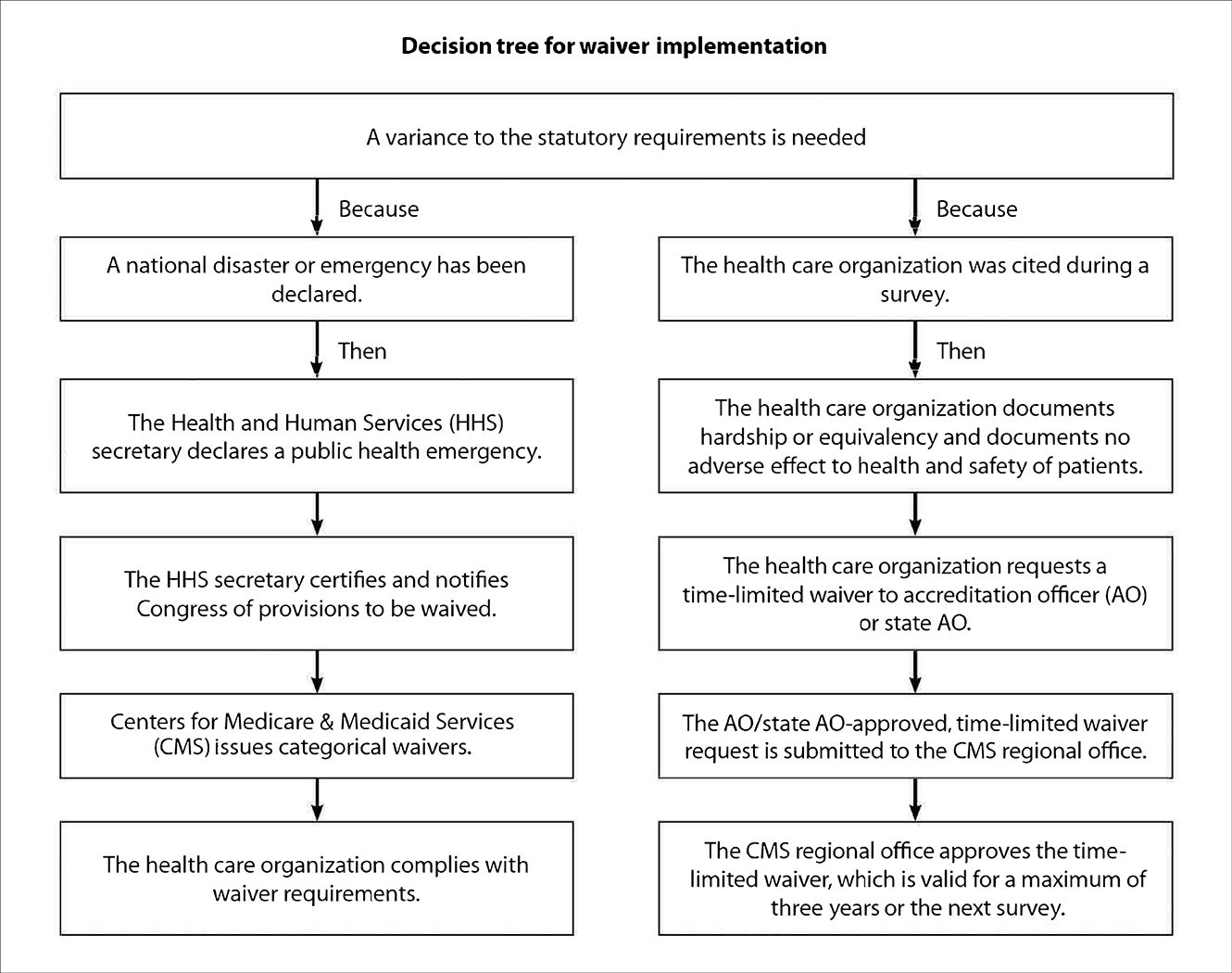

Temporary compliance. During an emergency, standard regulations may need to be temporarily waived. When making decisions about how to respond to an emergency, it is important to be able to identify the greater risk. There may not be an ideal solution in some situations, and there may be unknowns that make the decision even more difficult. Therefore, it is vital that a multidisciplinary approach be used in making decisions.

Federal, state and local governments or health departments may issue waivers or modifications to regulations in response to emergencies that affect a particular geographic area. These may be blanket waivers that apply broadly or waivers issued in response to requests from health care organizations.

ASHE has advised its members on using categorical waivers provided by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ASHE recommends that facilities check to ensure that their state accepts the waivers, ensure full compliance with the appropriate code reference mentioned in the waiver, document the decision to use the waiver and notify the appropriate parties orally and in writing.

While it may become necessary to suspend federal, local or organizational policies and procedures to protect patients, visitors and staff — as well as mitigate damage to the facility and equipment, supplies and other assets — it is important to consider the impacts of doing so. Additionally, changes to the health care physical environment can have unintended consequences that affect existing infection control precautions.

Health care facilities professionals should consider the impact on infection control when making emergency modifications to the health care facility infrastructure, including ventilation systems, electrical systems, medical gas systems, water and wastewater systems, contracted services, space utilization, networks and telecommunication systems.

Ventilation. Given the increased emphasis on ventilation requirements in health care spaces and the conflicting requirements of various authorities having jurisdiction, a comprehensive ventilation management plan (VMP) will help a health care organization manage ventilation and other heating, ventilating and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

A thorough VMP will help protect patients, staff and visitors from airborne pathogens and toxins and help a facility maintain compliance with all applicable accreditation, licensure and regulatory standards. This plan aims to create a comprehensive strategy to test and maintain all areas identified that require any type of ventilation management, including pressure, temperature, humidity, air changes or filter requirements. VMP floor plans can complement the VMP and provide mapping that shows the pressure risk ranking of spaces and direction of airflow from the spaces.

A VMP is ideally established and supported by a multidisciplinary committee and aims to identify, develop and implement effective strategies to manage and maintain ventilation and other HVAC systems with a focus on compliance, both during everyday operation and during an emergency response.

The American National Standards Institute/ASHRAE/ASHE Standard 170, Ventilation of Health Care Facilities (revised in 2021) offers guidance, regulation and mandates about the ventilation of health care facilities. Additionally, ASHRAE/ASHE Guideline 43, Operations Guideline for Ventilation of Health Care Facilities, is expected to be released later in the year.

Water systems. Wet environments pose a particular hazard of infection, promoting microbial growth and serving as a source for antibiotic-resistant pathogens and health care-associated infections.

It is important that a facility has an active water management plan (WMP), especially in case of emergencies. A WMP provides policies and procedures that inhibit microbial growth in building water systems and reduces the risk of growth and spread of waterborne pathogens.

Tap water meets stringent safety standards in the United States, but it is not sterile. Certain numbers and types of bacteria and other microbes may be present when water leaves the tap. The ways water is used in health care are varied, and patients might be more vulnerable to infection.

Certain conditions within health care plumbing systems can even encourage microbial growth. This can lead to dangerously high levels of potential pathogens.

Moreover, the risk does not stop at the tap. Every use of water in patient care settings must be scrutinized and evaluated for its risk as a reservoir or pathway for health care-associated pathogens. Even hospital sink drains and toilets can pose a risk for harboring antibiotic-resistant pathogens that can spread to patients and cause harm.

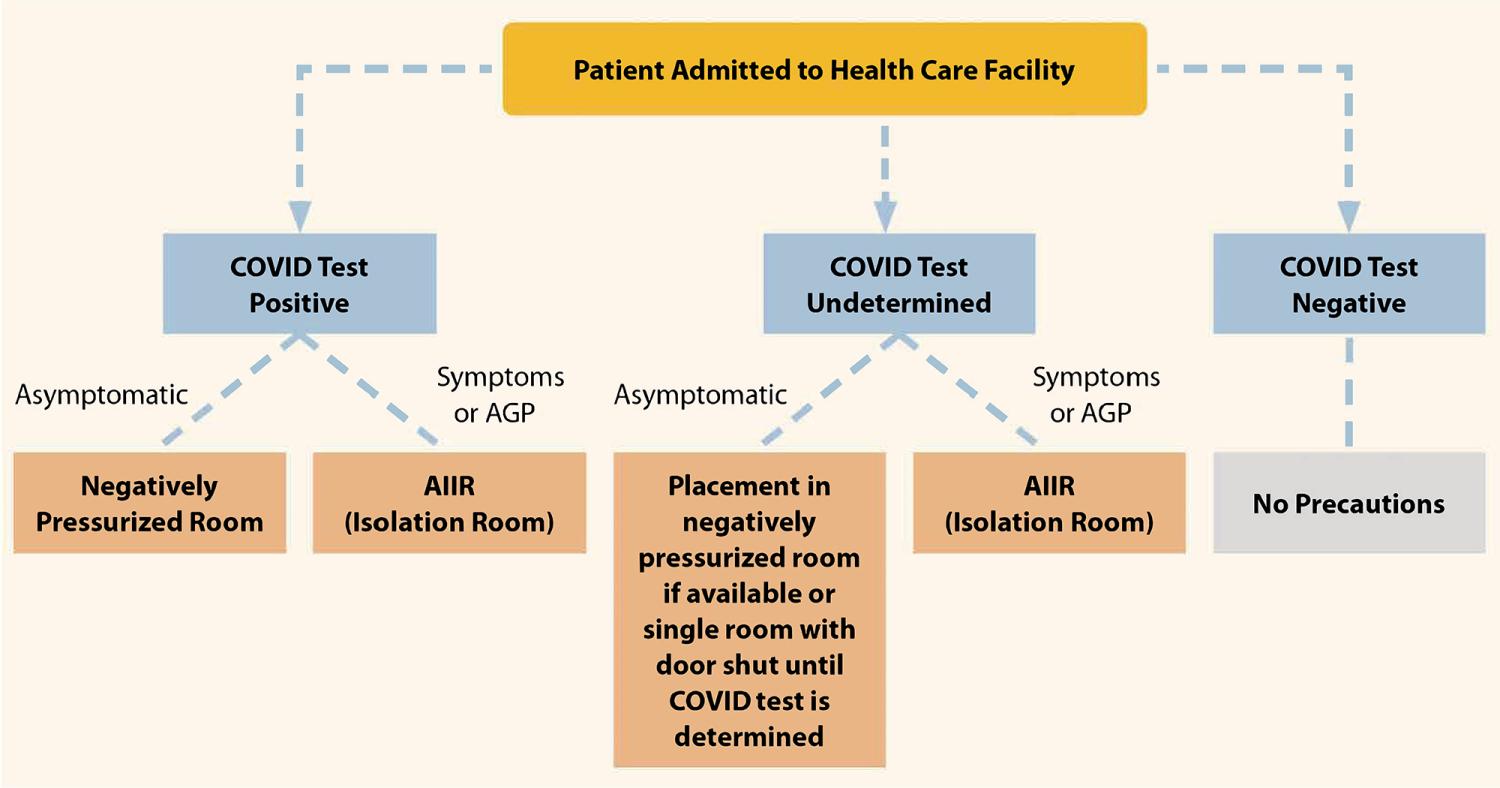

Dedicated units and co-location. One consideration that is specific to emergency situations involving outbreaks of infectious disease, environmental contamination, biohazard exposure or high-risk surging conditions is how a facility can best serve patients receiving care for infectious conditions while maintaining the safety of others.

The COVID-19 pandemic gave health care facilities experience testing various approaches to providing care for both patients with the virus and those with other health care needs. For example, some multi-hospital health systems designated an intensive care unit (ICU) in one hospital for COVID-19 patients only and excluded patients with COVID-19 from the ICUs in other buildings.

These lessons can be applied to other situations that produce a surge of patients with similar needs and who present similar risks to other patients and staff.

The decision-making around any approach should be led by the infection prevention and care teams, but facilities managers should be included in the decision-making process so that physical environment issues are considered and they are ready to support the best care possible for the patients.

Waste management. During the COVID-19 pandemic, no special requirements for trash disposal were issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). It remains unlikely that changes to standard waste management protocol will need to be made in the case of an emergency. Although waste management will rarely need to change due to an emergency, considering when an exception is needed should be part of emergency planning procedures.

Epidemiologic evidence does not suggest that most of the solid or liquid wastes (with the exception of sharps) from hospitals, other health care facilities or clinical/research laboratories are more likely to cause infections than residential waste. (Waste management guidance was issued for facilities treating patients with Ebola and Marburg virus, but not for other infectious diseases.) Therefore, identifying wastes for which handling and disposal precautions are indicated is largely a matter of judgment about the relative risk of disease transmission because no reasonable standards on which to base these determinations have been developed.

Aesthetic and emotional considerations originating during the early years of the HIV epidemic have, however, figured into the development of treatment and disposal policies, particularly for pathology and anatomy wastes and sharps. Public concerns have resulted in the promulgation of federal, state and local rules and regulations regarding medical waste management and disposal.

Health care facilities professionals should continue to follow these regulations in an emergency.

Personal protective equipment (PPE) and storage. PPE protocols have long been established in health care facilities, but the role of EVS in implementing operational changes and developing logistics involving PPE expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic and is likely to continue. This experience has shown that procurement, storage, distribution and collection of PPE may pose a significant challenge during emergencies and should be included in an emergency plan.

To help facilities plan for and conserve the use of PPE in response to increased use and demand, the CDC developed a PPE Burn Rate Calculator. Three general strata (conventional, contingency and crisis capacities) are used to describe surge levels and can be used to prioritize measures to conserve PPE supplies.

Patient flow. One of the lessons learned during the COVID-19 pandemic is that hospital design needs to support clear channels for circulation and flow of people to support safe movement and minimize transmission risk.

Creating facilities that have the flexibility needed to maintain operations during an emergency is essential. Facilities need to be safe and demonstrate safety to foster public trust and a return to care. Without this, there will continue to be a monumental impact on our health care delivery system.

These considerations are not specific to emergency planning, but incorporating them when building, expanding or remodeling health care facilities can make facilities more resilient in future emergencies.

Emergency situations may affect the flow of people through a health care facility.

- An all-hazards approach will account for such scenarios as:

- Entrances or roadways to buildings or campuses may be inaccessible due to damage, flooding or other factors.

- It may be necessary to limit entrances to doors where security or health screeners are stationed.

- Areas may need to be closed for restoration.

- Areas may be closed to the public but remain open for patients and staff.

- Flow changes may be necessary for infection control, such as the addition of triage/screening areas.

Factors to consider when supporting changes to flow include:

- Revisions to cleaning schedules if an area’s traffic patterns change.

- Nearby storage for screening or triage supplies if additional stations are set up.

- Wayfinding signage, including addition or covering/removal of exit signs and other wayfinding aids if entrances are limited.

- Adjustments to HVAC systems if needed to maintain air changes per hour and pressurization to a unit affected by changes to patient flow.

Health care facilities professionals should consider adding a checklist to the emergency plan with factors to consider for each type of change to patient, staff and public flow in the facility.

Surge capacity and alternate care

sites. Public health emergencies may result in surges of patients. An emergency plan should include plans for how to accommodate surges, whether they are expected to last for hours, days, weeks or months. There may also be emergencies that necessitate the closure of some or all of a health care facility, requiring the relocation of services.

Both situations may be addressed by temporary changes to a health care facility’s patient flow; layout, including how units are utilized; or whether an alternate care site can be activated. Building as much flexibility into the facility’s design as possible can assist with surge situations.

Understanding fundamentals

ASHE’s Emergency Management Playbook is intended to be a resource for use in planning for emergency situations and developing an emergency management program. It cannot address every emergency situation one might encounter or capture every variable at play.

While there will likely be situations in which an emergency response team needs to improvise, understanding the fundamentals in the playbook will help build a foundation upon which an emergency management team can make informed decisions that reduce risk, including infection control risks, to patients and residents as they arise.

RELATED ARTICLE: Balancing infection control and life safety requirements

As a result of the federal COVID-19 public health emergency declaration on March 13, 2020, strict adherence to and compliance with the usual code requirements, such as those found in the formally adopted 2012 editions of the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, and NFPA 101®, Life Safety Code®, were de-prioritized.

Subsequent to the declaration, in the last three weeks of March 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) suspended some of the normally mandated life safety code and emergency preparedness surveys at acute care hospitals, long-term care facilities and ambulatory health care occupancies, among others.

The need to manage and treat patients and protect health care workers from an infection prevention point of view became an imminent priority, thereby illuminating the intersections where infection control policies and practices were in competition with and, at times, in conflict with requirements for protection from fire — with some caveats.

These discrepancies, made more urgent by the surge in patient volume, underscored the need to prioritize infection control requirements and prompted CMS to issue these COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers.

In the landscape created by the pandemic, health care facilities professionals reported that the goal of the resultant temporary arrangements and configurations often was to provide a “sufficient level of safety” as opposed to the normal “standard level of safety” that health care facilities typically strive for. That does not mean that life safety and fire safety were set aside; however, it did mean that health care facilities professionals had to determine how to be flexible, where there could be some elasticity in the code requirements and where applying the equivalency provisions was most important.

Pandemic circumstances also, at times, forced organizations to activate “crisis standards of care.” The situation challenged physical space, staffing, available supplies and the level of care being provided to patients, a situation that the life safety requirements of NFPA 101 do not directly address.

Authorities having jurisdiction can look to related provisions (e.g., if care is being provided in tents, flame-retardant standards for tent materials can be consulted) to walk the line of accommodating the necessary level of patient care and incorporating some level of fire safety and fire protection.

This article was excerpted and edited by Health Facilities Management staff from the American Society for Health Care Engineering’s Emergency Management Playbook: A Back-to-Basics Approach to Infection Control and Emergency Management for Health Care Facilities.