Using data to optimize inpatient environments

ProMedica Toledo Hospital’s Generations of Care Tower.

Image © Tom Harris

Aiming to address the complexities of inpatient units while delivering exemplary care to Toledo, Ohio, and its surrounding communities, ProMedica, a Toledo-based health care organization, and the architectural firm HKS, used an evidence-based design (EBD) approach to develop the new Generations of Care Tower at the ProMedica Toledo Hospital campus in 2015.

The 756,600-square-foot, 13-story, 309-bed inpatient tower was designed to minimize waste, maximize staff efficiency, optimize functional performance, and enhance safety and quality. ProMedica’s vision emphasized delivering exceptional care while prioritizing efficiency and patient-centeredness. To achieve this vision, the architectural firm’s design and research teams worked collaboratively to inform the design of the surgical intensive care unit (SICU) and step-down acute care unit.

Although prior research provided valuable insights into the impact of nurse activity, walking distances, connectivity and patient visibility on workflow and effectiveness of care delivery in inpatient units, the team acknowledged the necessity of adopting a context-specific approach. This included careful examination of working conditions in the existing SICU and medical-surgical units to inform design decisions for the new units.

The resulting project has received numerous awards, including the Center for Health Design’s Touchstone Award for exemplary use of an EBD process in the physical environment.

Data-driven decisions

In pursuit of EBD, the team performed a design diagnostic — a study method that allows a deeper look into core operational and experiential issues — in the existing Renaissance Tower units using field research as well as off-site spatial analysis, as documented in an article published in the October 2020 edition of the Health Environments Research & Design (HERD) Journal titled “Practice-based research methods and tools: introducing the design diagnostic.”

Field research included a photo essay, noise level measurements, clinical and non-clinical staff interviews, behavior mapping and nurse shadowing conducted over 2 1/2 days. In addition, web-based surveys were administered to staff.

The off-site spatial analysis provided proximity and walking distance analyses using a parametric modeling tool. Valuable insights about the units, such as inadequate space for staff collaboration, excessive noise levels in the nurses station, unnecessary nurse walking, limited access to supplies, cluttered hallways and lack of staff connectivity and patient visibility, uncovered opportunities for improvement in the new Generations of Care Tower.

The data from the field research resulted in the development of simulation models that allowed the team to optimize the design throughout the process to support the goals of increased efficiency, improved team communication, increased patient safety, and enhanced patient and family experiences.

After the completion of construction and phased occupancy in the Generations of Care Tower, a functional performance evaluation (FPE) was conducted in 2021 to evaluate how effectively the new unit met user needs and supported organizational objectives.

The research team once again collected on-site data within the guides of the design diagnostic protocol that included a photo essay, shadowing, behavioral mapping, noise level readings and staff interviews. Additionally, a survey comprising 108 questions was administered to the staff to assess safety, efficiency, experience, access and flexibility in the units.

Key findings

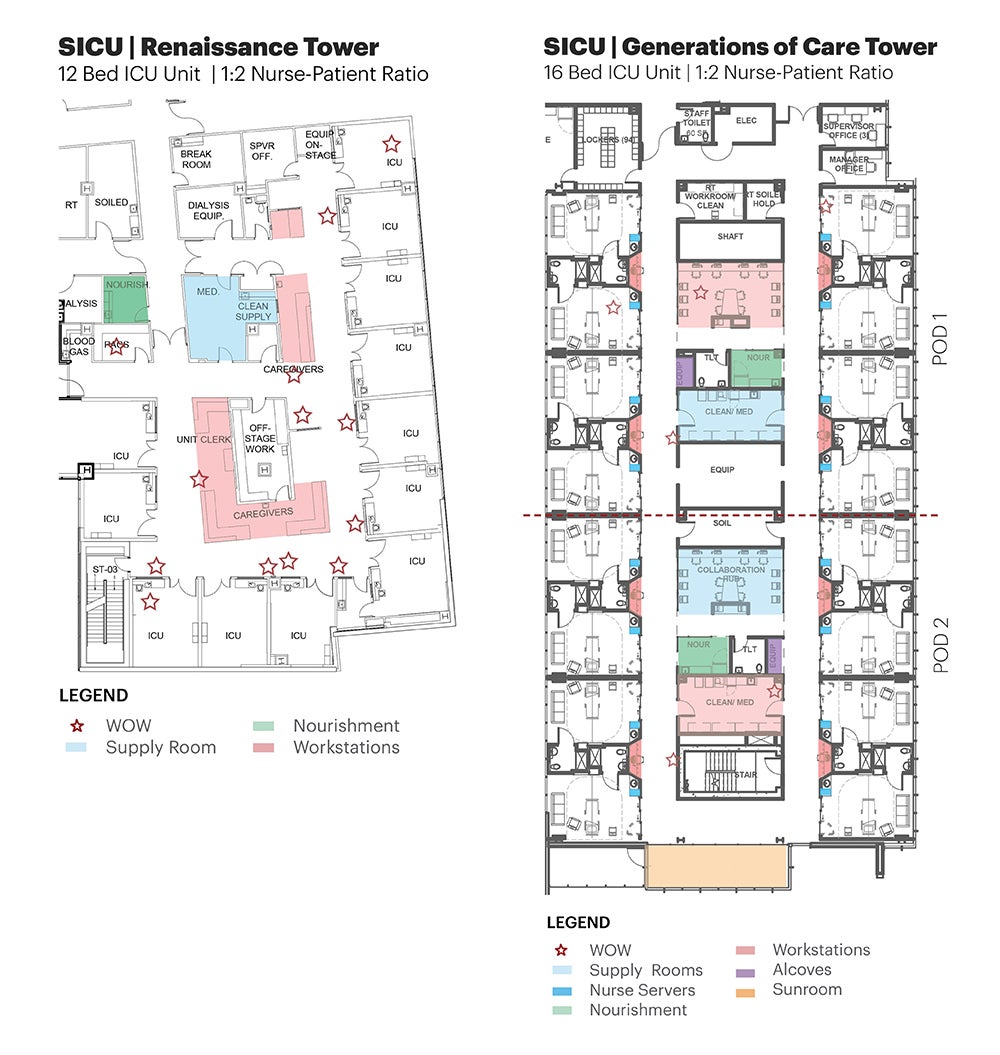

The medical-surgical unit in the existing Renaissance Tower comprised two wings, each with four nursing stations, 20 rooms, two medication and clean supplies rooms, one shared nourishment room, two soiled-linen rooms, two equipment rooms and four linen closets. The 12-bed SICU in the Renaissance Tower included four nurses stations, one medication and clean supplies room, one soiled-linen room, one equipment room and an off-stage work area.

In the Generations of Care Tower, the SICU and step-down units are co-located to enhance staff workflow and streamline patient transfers between critical and acute care. Furthermore, these units adhere to standardized layouts, patient room designs and nurse-to-patient ratios, facilitating staff mobility and ensuring familiarity across units.

The following discusses some key research findings from the design diagnostic in the Renaissance Tower, their translation to design strategies implemented in the new units at the Generations of Care Tower and the impact measured through a FPE one year after occupancy:

Nurse workflow and walking distance. The distance a nurse walks every day has been a growing concern as the nursing profession ages and nurse recruiting becomes more difficult. The project team tackled this challenge through the following process:

- Research finding. One of the most striking findings from the field study showed a single nurse’s travel distance to be 1.8 miles on the unit during a shift. Bedside nurses were particularly frustrated by the long walking distance to locations such as the nourishment rooms to get a small item like applesauce or juice for a patient. This comment came up repeatedly in face-to-face interviews and surveys of open-ended comments.

Analysis of the shadowing data revealed that the frustration could be linked to the sequence of activities related to nourishment room visits and the high frequency of visits for minor tasks or getting small items. For a high-acuity patient, the nurse may have to go to several touchpoints to accomplish multiple tasks.

For instance, they may go to the medication room, get medication and document, go to the patient bedside to administer the medication, then walk all the way to the nourishment room to get Jell-O or apple juice to have the medications with, return to the patient room and administer the medication. If the patient throws up, the nurse will then go back to the clean supplies room, get supplies, clean up the patient, pick up new linen, change the patient, drop-off soiled linen and then return to the nurses station for charting. Sometimes the nurse may have to go again to the nourishment room for ice and water to give to the patient. In this example, for this single medication event with a patient, the nurse would have walked to the nurses station, patient room, medication room, nourishment room, soiled utility and clean supplies room several times.

- Design response. This finding highlights the need for co-location of key support spaces as well as access to point-of-use supplies. This translated to the provision of two decentralized nourishment rooms within the central core, one for each pod of eight patient rooms in the new layout. Furthermore, a porous central core was designed with several cut-throughs. The challenges associated with limited point-of-use supplies were addressed by providing a dual-access nurse server in each patient room. Based on the simulation models, it was hypothesized that the new layout could reduce nurses’ walking distance by about 50%.

- Documented impact. In the FPE after occupancy, walking distance was calculated for the observed path from the nurse shadowing data for a single medication event. When compared to a similar nurse activity sequence in the Renaissance Tower, a 43% reduction was noted in the walking distance in the new Generations of Care Tower. Shadowing data also revealed that the nurse spent less time gathering supplies.

Collaborative and focused tasks. While collaboration is highly valued in health care delivery, it can also be a challenge to staff members who are attempting to focus. The project team tackled this challenge through the following process:

- Research finding. In the Renaissance Tower, nurses, physicians and other care team members used the nurses station both for documentation and as a touchdown space. The enclosed and designated off-stage area for team huddles obstructed unit visibility and was used as a hideaway space. The offstage area was mostly underutilized, adding pressure on the nurses station and making it a noise generator for the unit.

- Design response. The new unit was designed with two collaboration hubs to serve as interaction spaces for staff assigned to the front-eight and back-eight patient rooms. Centrally located and enclosed collaborative hubs with glass walls were designed within the narrow central core to allow visual continuity and connectivity across the unit while containing noise. Additionally, decentralized alcoves with windows looking into the patient rooms were designed to provide space for focused work, such as charting and care coordination, while simultaneously monitoring patients.

- Documented impact. While the charting alcoves outside patient rooms were designed with the intent of being the primary location for nurses, SICU nurses would frequently congregate in the front collaboration hub. The shadowed nurse spent much of the time during the shift (38%) in the collaboration hub discussing patient care needs and documenting. Only 3% of the shift time was spent in the nurse charting station.

A clutter-free corridor exudes a sense of openness while an enclosed, transparent collaboration hub offers visual connectivity to the unit and decentralized charting stations provide patient visibility.

Image © Tom Harris

Because patients in the SICU are critical, the ability to monitor patient information continuously trumps the need to be in proximity and have direct visibility to the patients. The presence of patient information on monitors in the collaboration hub is a reason for the collaboration hubs to be used as touchdown points by most nurses in the SICU. A certain level of nesting was observed with the other collaboration hub being used by physicians, care navigators, residents, respiratory therapists and others.

Contrary to the SICU, the acute care nurses were seen using the decentralized charting stations outside patient rooms to access the computer for documentation or during shift change handoffs.

Acoustic environment. Loud noises and other auditory distractions can add stress to the environment, leading to medical errors and disrupting patient rest, among other issues. The project team tackled this through the following process:

- Research finding. In the Renaissance Tower, noise levels on the unit were found to be more than the World Health Organization guidelines of 35 decibels (dBs) for nighttime and 40 to 45 dBs for daytime. The average noise level in the unit was around 50 dBs at night and 65 dBs during daytime. Peaks were as high as 102 dBs due to sharp noises, such as doors closing, drawers slamming or ice machines dispensing. During the design diagnostic, workstations on wheels (WOWs) were frequently located in the corridor or cluttering the main nurses station, resulting in increased sound levels.

- Design response. Key sources of noise, such as ice machines and pneumatic tubes, were tucked within the core away from the primary corridors. Also, alcoves were designed for parking WOWs that could minimize clutter in the hallways.

- Documented impact. The average daytime noise level recorded on the Generations of Care Tower units was 48 dBs. A significant reduction in average daytime noise levels was found when compared to the Renaissance Tower medical-surgical unit. There was a notable increase in top-box percentages for quietness of hospital (6.61%) in 2021 as compared to the average of the previous years. Moreover, most staff (83%) reported to be satisfied or highly satisfied with the acoustic environment in the unit.

Lessons learned

The team successfully delivered solutions rooted in research that elevated the patient and staff experience. Strategic co-location of the SICU and step-down unit, thoughtful placement of collaboration hubs and optimization of spatial arrangements have proven instrumental in enhancing nurse satisfaction and workflows. Several lessons learned during this FPE turned into opportunities for improvement for this and several other projects.

For instance, nesting behaviors in the collaboration rooms made it challenging to operationalize the pod model as envisioned. This can be attributed to the lack of appropriately conveying the design intent to the staff on the floor and unit leadership changes during the transition. It was observed that in the units where managers were part of the design process, the collaboration rooms were being utilized as designed.

It is important that design-intent documentation is accompanied by an operational handbook and functional narrative so that units are operated the way they are planned, irrespective of leadership changes, while remaining agile to new challenges. A three-month, six-month and 12-month check-in between the design team and operational team is recommended to help with a smooth transition.

While the physical environment is a crucial component of the intricate health care system, organizational policies, technology and user behaviors also play significant roles in shaping experiential and operational efficiency.

The complexity of health care design projects necessitates a comprehensive approach that goes beyond traditional methods. Incorporating timely field insights and analytical tools enabled designers to develop nuanced and innovative solutions that complement client feedback and desktop research. Design diagnostics (before and during design) and FPEs (after occupancy) stand as indispensable tools that offer critical perspectives that bookend the design process and ensure the effectiveness of design solutions toward maximum impact.

RELATED ARTICLE: Point of care supply process improves workflows and care

Improving quality and efficiency while controlling costs is imperative across health care. While the supply chain concentrated on reducing redundancy and waste through vendor relationships, pricing strategies, product utilization and standardization, frontline clinicians were observed dedicating 17% of their workday, roughly two hours per shift, to managing inventory issues.

Dual-access nurse servers provide point-of-care access to supplies.

Image © Tom Harris

By ensuring timely access to products, clinicians can devote more time to patient care, potentially enhancing outcomes, quality, safety and satisfaction. Time spent looking for supplies leads to a lack of trust manifested in hoarding supplies. Supplies are stashed in drawers in patient rooms, on counter tops and in scrub pockets. End user workarounds lead to waste, stockouts and a potential for expired products.

There is a lack of evidence-based approaches in the literature when it comes to point-of-care supply models. Understanding the existing challenges, the team embarked on designing an innovative point-of-care supply system to streamline clinical workflows and enhance patient care.

Following several rounds of mock-ups, user feedback and design iterations, dual-access nurse servers were designed in each patient room to stock linen, frequently used supplies and medication as well as a trash pull-out.

Staff reported that it offered increased flexibility and safety, a crucial advantage during the COVID-19 pandemic. The functional performance evaluation showed that the average time spent looking for supplies significantly reduced to 7% of the shift. While nurses primarily accessed the nurse server to obtain medication or supplies for the patient from within the patient room, there were several instances of walking to the nurse servers of other patient rooms due to stocking shortages.

This highlights the importance of a comprehensive approach in the future, going beyond physical space and taking into consideration stocking schedules, inventory management strategies at the organizational level and utilizing technology to track supply consumption patterns.

About this article

This feature is one of a series of articles published by Health Facilities Management in partnership with the American College of Healthcare Architects.

Rutali Joshi, Ph.D., EDAC, LSSYB, is associate and senior design researcher for health; Camilla Moretti, ACHA, LSSGB, LEED AP BD+C, AIA, is principal and studio practice leader for health; and Upali Nanda, Ph.D., EDAC, ACHE, Assoc. AIA, is executive vice president and global sector director for innovation at HKS. They can be reached at rjoshi@hksinc.com, cmoretti@hksinc.com and unanda@hksinc.com.