Sustainable strategies for small, rural hospitals

Small rural hospitals serve as lifelines for their communities but many have seen little modernization since their inception.

Image by Getty Images

The Hill-Burton Act of 1946, formally known as the Hospital Survey and Construction Act, laid the groundwork for many small rural hospitals across the United States that serve as lifelines for their communities.

However, many of these hospitals have seen little modernization since their inception. Pressures to decarbonize the health care sector, driven by initiatives like the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) Health Sector Climate Pledge and The Joint Commission’s Sustainable Healthcare Certification, present challenges and opportunities for these institutions.

Strategies for small rural hospitals to become more sustainable with limited resources, emphasizing the importance of education, leadership and early engagement in decarbonization efforts, are discussed here.

Contemporary challenges

The 2022 American Hospital Association Annual Survey found 6,120 hospitals in the U.S. Of those, 5,129 were listed as “community hospitals,” and that category was further broken down into not-for-profit community hospitals (2,987), for-profit community hospitals (1,219) and state and local community hospitals (923). These numbers show that a significant segment of U.S. hospitals can be considered small, reinforcing the importance of doing more with less.

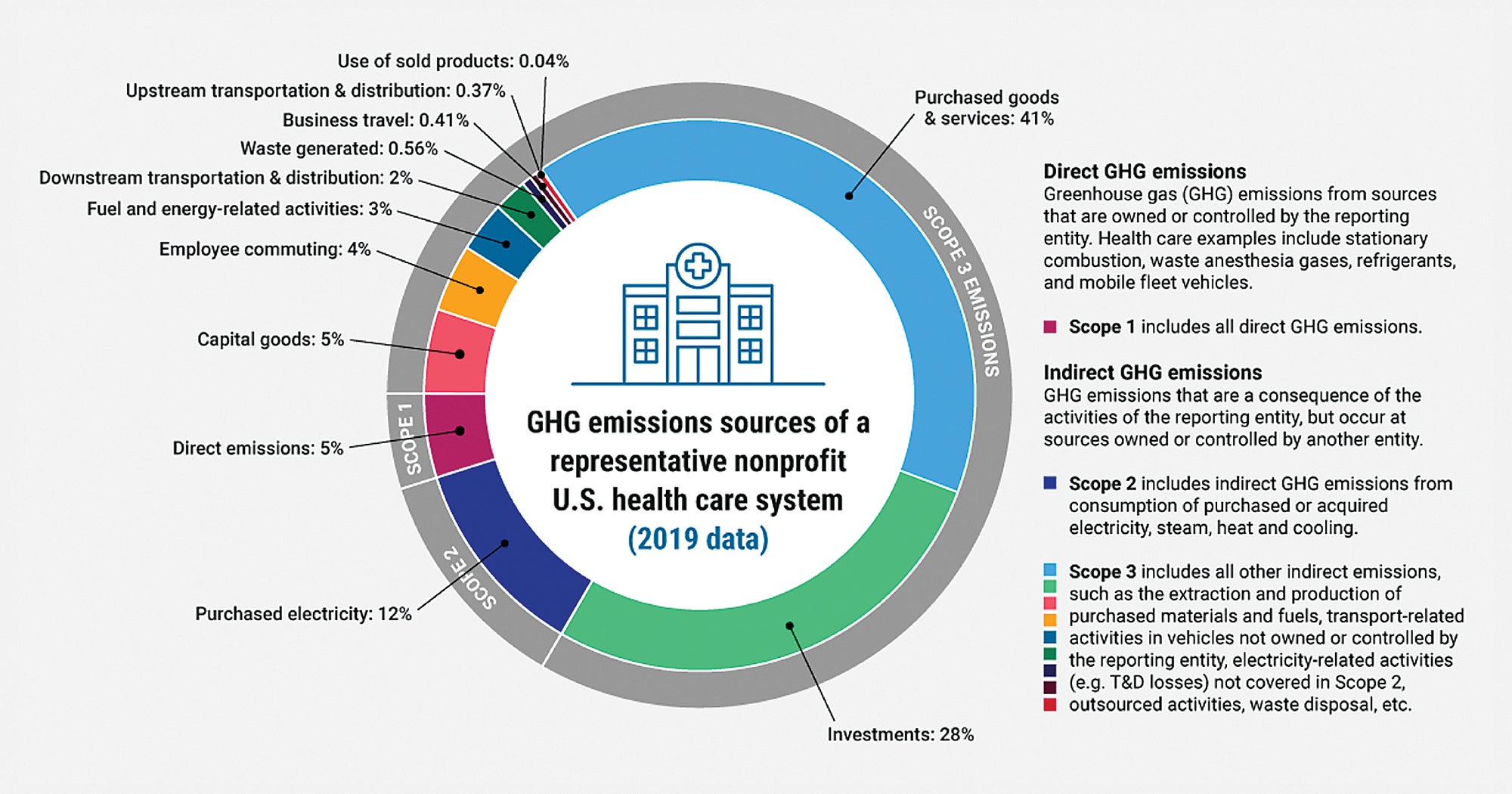

According to the World Health Organization, health care contributes 8.5% of greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the U.S., driving pressure for the sector to address its environmental impact. Health care institutions are being compelled to adopt strategies that incorporate decarbonization, operational efficiency and other ways to reduce their organizations’ carbon footprint. Some health care organizations have made substantial progress, while others are making small steps, with the differences generally connected to small versus large systems.

This movement toward sustainability comes from various factors, such as the global ecological crisis as well as standards and regulations being set by health care leaders and governmental entities. Several groups have issued policies and programs to help the health care industry adopt sustainability practices:

The HHS Health Sector Climate Pledge. The White House and HHS launched the Health Sector Climate Pledge on Earth Day 2022, underscoring the federal government’s commitment to carbon reduction. By setting this standard, the pledge encourages hospital leadership to expand support to the communities they serve. It reinforces the idea that health care’s responsibility goes beyond patient care and encompasses a commitment to environmental stewardship. As of April 2024, 139 organizations representing 943 hospitals have signed the pledge.

The Joint Commission’s Sustainable Healthcare Certification. In September 2023, The Joint Commission introduced its new Sustainable Healthcare Certification as a voluntary opportunity beginning in January 2024. This certification allows organizations the ability to expand or continue their sustainability efforts while gaining recognition of their achievements. This emphasis on sustainability reveals the connection between health care quality and environmental stewardship.

The National Academy of Medicine. In response to the need to address the impacts of the changing climate, the National Academy of Medicine in 2020 launched the Grand Challenge on Climate Change, Human Health & Equity, to help with decarbonizing the U.S. health care sector. The collaborative is a public-private partnership of health care sustainability leaders who are committed to addressing the impact and helping the health care field become more sustainable.

Understanding and educating

To navigate the complexities of decarbonization, small rural hospitals must educate and train all levels of leadership, from the boiler room to the boardroom. Understanding the carbon boundaries of hospitals and systems is essential. Maintenance leaders play a crucial role in initiating emissions control measures, often through energy reduction and savings initiatives. By aligning these efforts with decarbonization goals, hospitals can maximize their impact with limited resources.

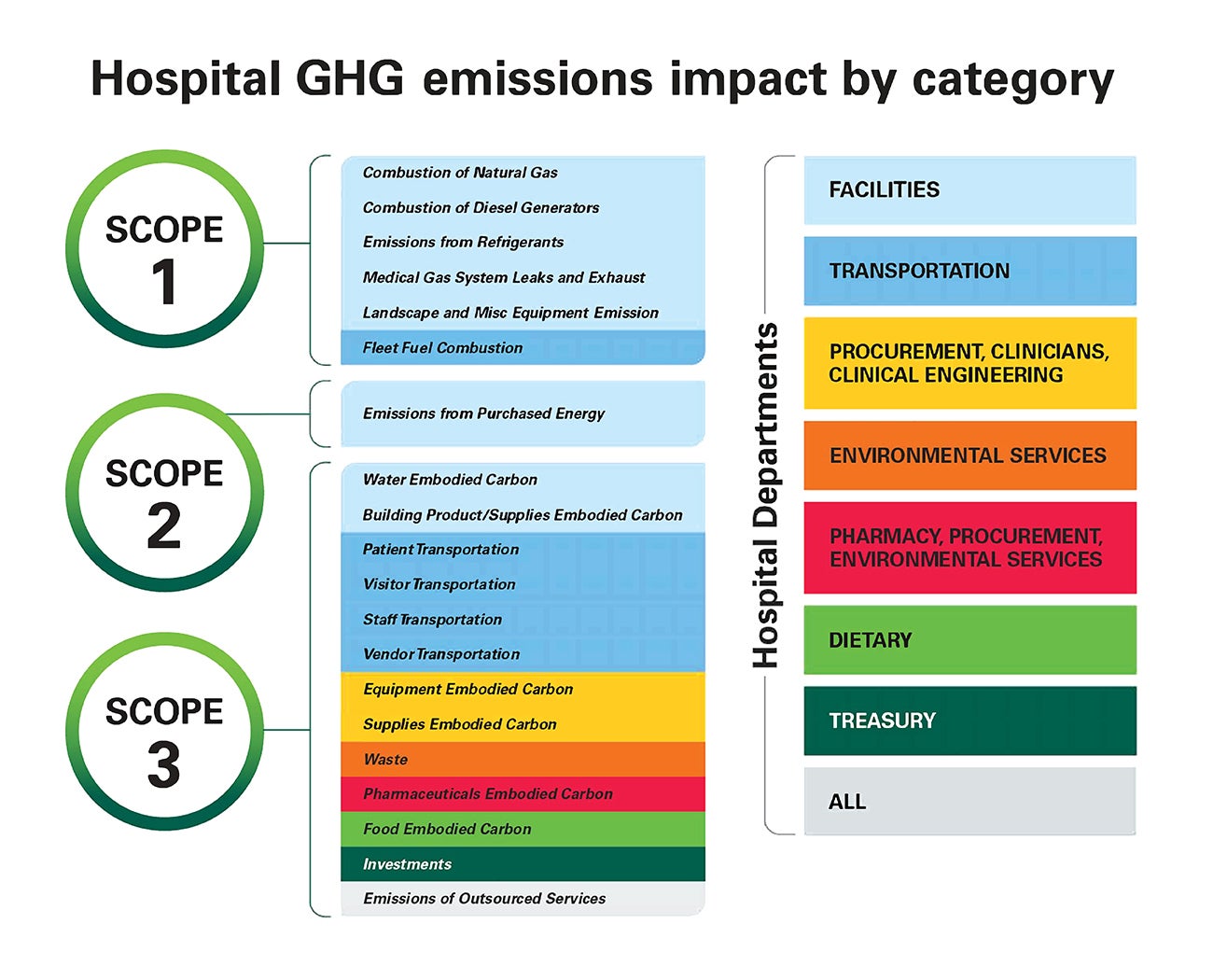

GHG emissions are categorized into three main categories, known as scopes, which provide a framework for organizations to assess and manage their emissions. These categories were established by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, developed by the World Resources Institute and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development. The protocol defines each category as:

Scope 1. This refers to direct GHG emissions that occur from sources that are owned or controlled by the reporting organization. This includes emissions from on-site combustion of fossil fuels in boilers, furnaces, vehicles and other equipment, as well as emissions from industrial processes. Scope 1 emissions are considered the most direct and readily controllable emissions for an organization.

Scope 2. This encompasses indirect GHG emissions associated with the generation of purchased or acquired electricity, steam, heating and cooling consumed by the reporting organization. These emissions occur outside of the organization’s direct control but are a result of its activities. Scope 2 emissions are often associated with the electricity consumption of buildings, manufacturing processes and other operations.

Scope 3. This includes all other indirect GHG emissions that occur as a result of the activities of the reporting organization but are not included in Scope 1 or Scope 2. These emissions can occur throughout the organization’s value chain, including upstream and downstream activities such as purchased goods and services, employee commuting, business travel, waste disposal and product use. Scope 3 emissions typically represent the largest portion of an organization’s carbon footprint but are also the most challenging to measure and manage due to their complex and diffuse nature.

A fundamental understanding of these emissions categories is critical to embarking on the decarbonization journey.

Building momentum

When embarking on the journey toward decarbonization, it’s crucial to start small and build momentum from familiar territory. By identifying lower-cost, higher-return investments, hospitals can swiftly demonstrate tangible progress and build confidence among staff and stakeholders.

Moreover, starting with what one knows provides a foundation for learning and growth, laying the groundwork for tackling more difficult tasks as a hospital progresses on its decarbonization journey, which includes the following considerations:

Identifying lower-cost, higher-return investments. Decarbonization doesn’t always require massive capital investments. In many cases, simple and cost-effective measures can yield substantial energy savings and emissions reductions. For example, implementing energy-efficient lighting, optimizing HVAC systems and upgrading insulation can significantly lower energy consumption without exorbitant costs. By prioritizing investments based on their potential returns, small rural hospitals can maximize their impact while minimizing financial strain.

The alternative is to identify impactful work that can be accomplished in a do-it-yourself manner that can include timely filter management; a steam trap program utilizing in-house staff; human element activities, such as turning the light out when a room is not in use; and controls programming for occupied and unoccupied schedules.

Facilities professionals should leverage free information provided by professional organizations such as the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) Sustainability Roadmap for Health Care™. This valuable resource is a repository of training, guides, tips and more.

Full-spectrum approach to sustainability. To achieve meaningful decarbonization, small hospitals must take a comprehensive approach that addresses all aspects of their operations. This includes not only retrocommissioning (RCx) heating, ventilating and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems but also domestic water usage, waste management and transportation. Hospitals can minimize their environmental footprint while enhancing operational efficiency and resilience by adopting sustainable practices across the board, including:

- RCx HVAC. According to ASHE’s Health Facility Commissioning Handbook, RCx “is a process intended to improve building performance in line with the owner’s expectations and design intent.” By optimizing the performance of existing HVAC systems through RCx processes, small hospitals can achieve significant energy savings and lower carbon emissions without costly infrastructure upgrades. This not only improves indoor comfort and air quality for patients and staff but also lays the foundation for broader sustainability initiatives by demonstrating the tangible impact of proactive environmental stewardship.

- Domestic water usage. Effectively managing domestic water usage is a crucial aspect of decarbonization in small hospitals, as it not only conserves water resources but also reduces energy consumption associated with water heating and distribution. By implementing water-efficient fixtures, hospitals can significantly decrease water usage and the energy required for pumping and treating water. Moreover, incorporating water-saving strategies into operational practices, such as laundry and dishwashing processes, can yield substantial water and energy savings over time. Coordinating these efforts with the water management program is vital to avoid waterborne pathogen concerns.

- Waste management. By implementing waste reduction, recycling and composting programs, small hospitals can minimize the amount of waste sent to landfills, thereby mitigating methane emissions — a potent GHG produced during the decomposition of organic waste. Additionally, adopting practices such as source segregation, where waste streams are separated at the point of generation, facilitates recycling and diversion of materials from landfills, further reducing carbon emissions. Finally, hospitals can implement composting initiatives to manage organic waste effectively, thus contributing to the reduction of their environmental footprint.

- Transportation. Transportation management in small hospitals is a pivotal strategy in advancing decarbonization efforts, as it targets emissions from vehicular operations while simultaneously enhancing efficiency and sustainability. Optimizing vehicle fleets through the adoption of electric or hybrid vehicles, as well as improving routing and scheduling practices, can significantly lower emissions from hospital transportation activities.

Other options and opportunities. Small rural hospitals may not always be aware of the options and opportunities available for decarbonization. But, by engaging with industry experts such as ASHE, collaborating with local utilities and networking with other health care facilities, hospitals can uncover innovative solutions tailored to their specific circumstances. Whether it’s new construction, renovations or major equipment replacements, utility companies may offer substantial financial incentives for energy reduction projects. From energy audits to renewable energy incentives, there are numerous resources available to help hospitals identify and implement decarbonization strategies, including:

- Sustainable design and construction. Hospital design and construction present valuable opportunities to integrate sustainability into hospital infrastructure. By prioritizing energy-efficient materials, incorporating renewable energy sources and optimizing building layouts for natural light and ventilation, hospitals can reduce their environmental impact from the outset.

Additionally, this can be an opportunity to make improvements in efficient operations like incremental upgrades to building automation system (BAS) technology and adding strategic infrastructure of emergency power for sustained operations.

Another emerging concept is electrification. This refers to the transition from traditional energy sources, such as fossil fuels, to electricity-powered systems and technologies within health care facilities. It is driven by the need to reduce carbon emissions, improve energy efficiency and enhance sustainability in health care infrastructure. Electrification encompasses various aspects of health care design, including building systems, medical equipment and operational processes.

Additionally, by minimizing construction waste, hospitals can lower construction costs and impacts.

- Leveraging BASs. Many small rural hospitals already have BASs in place to monitor and control mechanical equipment. These systems can be invaluable for identifying opportunities for energy savings and optimizing building performance. By leveraging data from BASs, hospitals can pinpoint inefficiencies, detect equipment malfunctions and fine-tune energy usage to maximize efficiency.

Incentives and funding sources. Small rural hospitals may be eligible for incentives and other funding sources. Early adoption and engagement in decarbonization efforts can position these institutions to leverage available resources effectively. These incentives and opportunities include:

- Utility company incentives. Utility companies are increasingly offering financial incentives that present valuable opportunities for small hospitals to accelerate their decarbonization efforts. These incentives, often in the form of rebates, grants or discounted rates, can offset the upfront costs associated with implementing energy-efficient upgrades and renewable energy projects.

For instance, utility programs may provide incentives for installing energy-efficient lighting, upgrading HVAC systems or investing in renewable energy technologies, such as solar panels or geothermal heating. By leveraging these incentives, small hospitals can not only reduce their energy consumption and carbon emissions but also lower their operating costs and improve their bottom lines.

Additionally, utility-sponsored energy efficiency programs may offer technical assistance and resources to help hospitals identify and implement cost-effective sustainability measures. Overall, partnering with utility companies and taking advantage of available financial incentives can empower small hospitals to make meaningful progress toward decarbonization while enhancing their financial sustainability and resilience.

Tools such as the Environmental Protection Agency’s ENERGY STAR® Rebate Finder and UtilityGenius can quickly find rebates that can help offset the cost of projects, thus relieving the strain of available capital.

- Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Elements of the IRA offer valuable avenues for small hospitals to advance their decarbonization goals while simultaneously reducing operational costs. These are new opportunities for not-for-profit health care as of January 2020, when the IRA was signed into law. Health care facilities professionals are strongly encouraged to check with financial and legal experts when exploring these opportunities.

Section 179D of the tax code, which was enhanced under the IRA, provides tax deductions for energy-efficient improvements made to commercial buildings, including hospitals, incentivizing investments in technologies that enhance energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions. Section 179D requires that the project initially meet a 25% reduction in energy consumption to be eligible.

It is also important to understand that the 179D incentive is not a “direct pay” incentive. This means that the entity receiving the benefit of the reduction would “allocate” the value of the calculated incentive to the designer or contractor. The value of the deduction is not dollar-for-dollar and is subject to the allotee’s tax bracket.

Navigating an initial 179D opportunity requires a bit of investigation and understanding of the law but can no doubt help to offset costs and improve returns.

Similarly, the Investment Tax Credit under Section 48 of the tax code, which was amended by the IRA, offers credits for renewable energy projects, such as solar photovoltaic systems or geothermal heating and cooling systems, enabling hospitals to transition to clean energy sources and further mitigate their environmental impact. This incentive is a “direct pay” incentive, meaning that, if eligible, the owner can file a modified tax form (Form 3468) the year that the project goes into service and will receive a check back in the value of the calculated incentive.

By leveraging these incentives, small hospitals can offset the project costs of implementing energy-saving measures and renewable energy solutions, making decarbonization more financially feasible and attractive. It is important to explore each of the eligibility requirements of these incentives to set expectations up front.

Unique challenges

Small rural hospitals face unique challenges in becoming more sustainable, but with strategic planning and collaboration, they can overcome these obstacles. By embracing decarbonization initiatives and leveraging available resources, these institutions can enhance their resilience and environmental stewardship.

Educating leadership, understanding carbon boundaries and seizing funding opportunities are critical steps toward a more sustainable future for small rural hospitals and the communities they serve. Early adoption and engagement will be key in navigating the evolving landscape of health care sustainability, ensuring that these vital institutions thrive for generations to come.

A final important reminder is that there needs to be a motivation to start this work now. The legislative and regulatory landscape is susceptible to quick changes that can lead to mandates for auditable programs, so an early start could be beneficial.

G. Andy Woommavovah, CHFM, SASHE, is vice president of facilities, construction and sustainability at Trinity Health in Livonia, Mich. He can be reached at andy.woommavovah @trinity-health.org.