ASHE publishes revised infection control risk assessment guide

The use of ICRAs during health care facility design and construction projects has been evolving for several decades.

Image by Getty Images

The use of infection control risk assessments (ICRAs) during hospital design and construction projects has been evolving for the past several decades, according to the publication Using the Health Care Physical Environment to Prevent and Control Infection, published by the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE) and other professional groups and associations in cooperation with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

The first formal ICRA was introduced in the 1996 edition of the Facility Guidelines Institute’s (FGI’s) Guidelines for Design and Construction of Hospital and Healthcare Facilities, although earlier editions required construction and renovation assessments related to specific risks. The goal of the assessment was to “describe how an organization determines the risk for transmission of various infectious pathogens” through a multidisciplinary committee.

A subsequent effort was undertaken by ASHE with other organizations and experts in the field to clearly spell out what would be included in the ICRA process. In 2020, ASHE assembled another group of experts to update these guidelines, which is being called ICRA 2.0.

Background on ICRA

The early context resulted in the ICRA becoming a part of prevention planning solely for construction activity. A 1996 study by Kennedy, et al., titled “Use of risk matrix to determine level of barrier protection during construction activities” and referenced in the aforementioned AHA/CDC publication, noted the first references to present the use of a risk matrix for barriers during construction.

This led to what is now commonly used as an ICRA precautions matrix. The acronym “ICRA” appeared in the 2001 edition of the Guidelines, where the process was mandated as a continuous activity throughout project programming, planning, design and construction.

In a 2007 paper referenced in the AHA/CDC publication and titled “Construction: A model program for infection control compliance,” Kidd, et al., outlined a compliance process following the implementation of a contractor training program; and in a 2014 paper referenced in the AHA/CDC publication and titled “The inherent safety value of using a dedicated infection control practitioner for infection control risk assessments,” Moore and Huber described an improved ICRA compliance process following the assignment of a construction-trained infection preventionist to construction activities.

In a 2014 paper referenced in the AHA/CDC publication and titled “To err is human — Using a systems-centered approach to minimize environment of care errors during construction and renovation,” Johnson and Lenz retrospectively identified the underlying conditions leading to errors during construction using a human factors framework.

In a 2015 paper referenced in the AHA/CDC publication and titled “The infection control risk assessment (ICRA) leads the way: Birth of the new safety risk assessment (SRA) process for design and construction,” Dickey and Taylor presented the most recent requirements for a proactive multidisciplinary safety risk assessment that appeared in the 2014 FGI Guidelines.

The SRA requirements are largely based on the framework established by the ICRA, and infection control is one of multiple safety components to be considered during hospital and health care facility design and construction projects.

More recently, the Guidelines has described the ICRA as a proactive and integrated process for planning, design, construction and commissioning activities to “identify and plan safe design elements, including consideration of long-range infection prevention; identify and plan for internal and external building areas and sites that will be affected during construction/renovation; identify potential risk of transmission of airborne and waterborne biological contaminants during construction and/or renovation and commissioning; and develop infection control risk mitigation recommendations to be considered.”

The ICRA in the Guidelines envisioned a long-range involvement of infection control and epidemiology leadership. The ICRA process needs to be advanced through explicit thinking about safety science and complexity of health care facilities and how these concepts can be supported by health care facility design.

Resources

Facility owners are responsible for conducting an ICRA using an expert multidisciplinary team. Based on the FGI Guidelines, the goal of the assessment is to “describe how an organization determines the risk for transmission of various infectious pathogens.” Originally, the early context of the ICRA focused on the prevention planning solely for construction activities; however, inclusion of infection prevention considerations systematically during project designs were not integrated.

Inclusion of the ICRA process into the design and operations of facilities is vital to fulfilling the responsibility of coordinating the infection control needs of the organization with the appropriate requirements for the isolation of infectious disease. The concern that the ICRA process has not been fully incorporated into the design and operations of many organizations is an issue that ASHE determined needed to be addressed.

ICRA 2.0 project

In July 2020, ASHE put together a multidisciplinary team consisting of infection prevention and control, industrial hygiene, construction, facilities management specialists and authorities having jurisdiction to evaluate the existing ICRA guide and to see how it could be improved to better serve health care organizations. This team met on a weekly basis throughout 2020 and into the first quarter of 2021 to accomplish this objective.

One of the key improvements the team made was to expand on the descriptive language throughout all the tables. The team spent several months discussing the various changes to ensure that all aspects of the tables were considered. This provided greater clarity for the application of the ICRA.

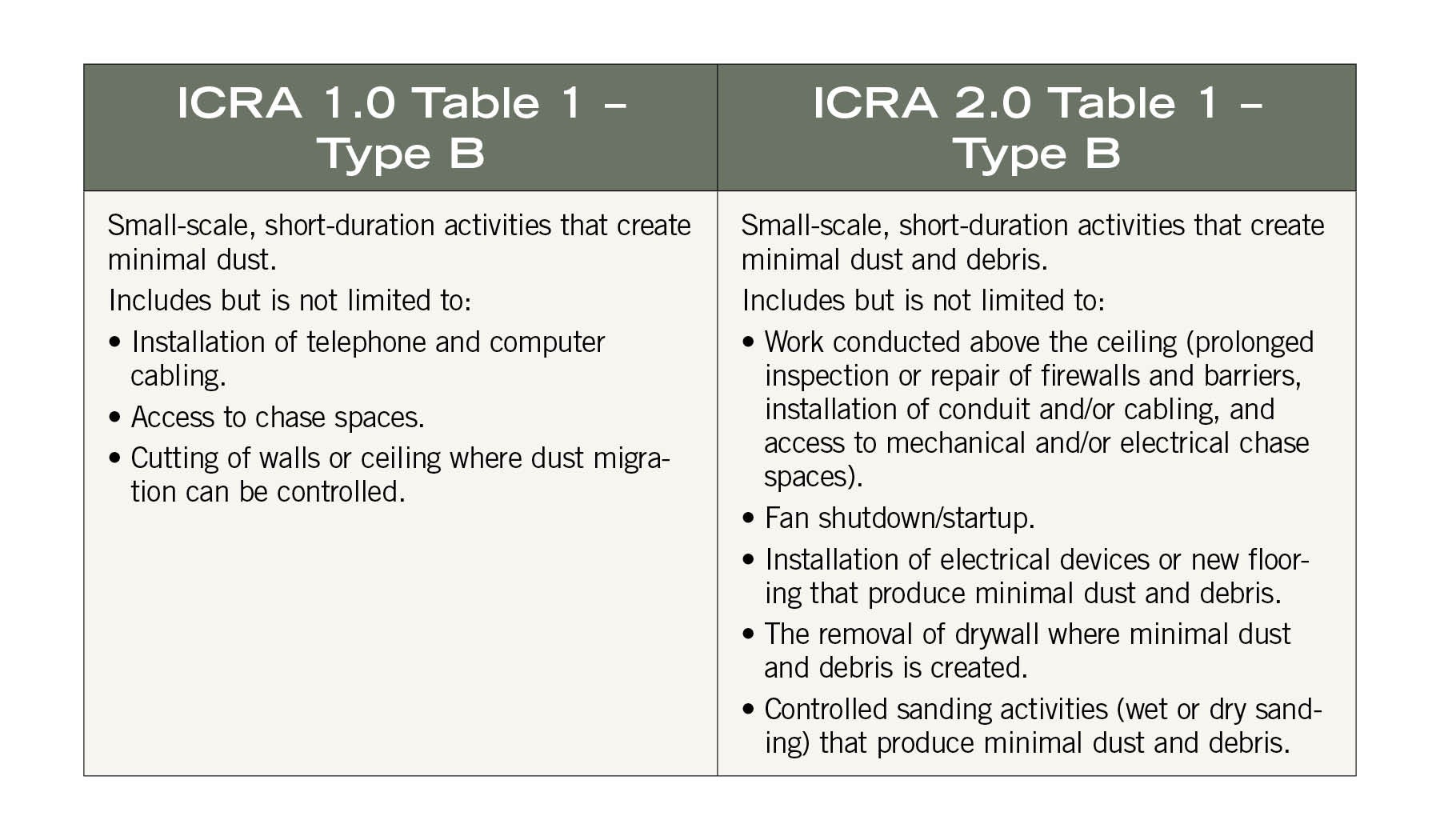

The chart on this page illustrates the expanded descriptions of “Type B” construction activities in the revised document’s “Table 1 – Construction Project Activity Type.”

The expansion of Type B to include prolonged inspection or repair above ceilings, fan shutdown/startup, installation of new flooring, removal of drywall where minimal dust and debris is created, and controlled sanding activities provides much greater clarity about the types of activities that fall within this category.

While several of these may have been referred through the current activities listed, the team realized during their review that there were types of work, such as prolonged inspections above ceilings, that were not clearly discernable from the current listing.

The important clarification provides teams with a greater understanding of how to apply the ICRA guidance and the types of activities that pose a risk to patients and staff.

Additional construction project activity types that the team clarified are:

- “Type A” expanded construction activities saw the broadening of building system maintenance by including pneumatic tube stations, HVAC systems, fire suppression systems, electrical activity and carpentry work to include painting without sanding. It also includes clean plumbing activity that is limited in nature.

- “Type C” expanded construction activities now include large-scale, longer-duration activities that create a moderate amount of dust, including removal of preexisting floor coverings, walls, casework or other building components; renovation work in a single room; nonexisting cable pathway or invasive electrical work above ceilings; removal of drywall where a moderate amount of dust and debris is created; dry sanding where a moderate amount of dust and debris is created; and work creating significant vibration and/or noise.

- “Type D” expanded construction activities include removal or replacement of building system component(s); removal and installation of drywall partitions; invasive large-scale new building construction; and renovation work in two or more rooms.

In the revised ICRA’s “Table 2 – Patient Risk Group,” the team added a description for each risk area and made several changes to the various risk groups. These changes included the addition of patient care support areas that were not originally part of the risk areas. These areas were placed within the medium risk areas.

Another significant change the team made within this part of the ICRA document was moving all patient care areas to the high-risk category and any invasive patient care to the highest-risk category.

This was discussed at length, and the consensus was that all patient care puts individuals at a high risk of exposure to possible infectious pathogens, and any time an invasive procedure is performed places a patient at the highest risk along with the original immunocompromised patients.

The team discussed at length the significant impact that these changes would have because this table directly impacts the outcome of the class of precautions matrix. A comparison of the changes is illustrated in the Table 2 sample charts on this page.

Within the revised ICRA’s “Table 3: IC Matrix – Class of Precautions: Construction Project by Patient Risk,” the team added a fifth class of precautions, which is detailed in “Table 5 – Minimum Required Infection Control Precautions by Class.”

The need for an additional class of precautions was one of the first issues discussed by the team. It was felt by many that the four classes limited the ability to properly address large-scale projects. This was evident in the original matrix, which had four categories that were both a Class III and a Class IV. The addition of a fifth category allowed the team to make greater distinction between Class II, III, IV and V categories.

The major changes are the designation that Class II is not to be used for construction or renovation activities. While this may seem counterintuitive, the team has designated Class I for noninvasive work and inspections, and Class II for standing practice procedures.

Standing practice procedures are activities that are routinely performed within the organization, such as patching of walls. The intent is that these types of activities would be covered under a standing practice procedure mitigation strategy developed by the multidisciplinary team through a one-time ICRA process. This would then be available to be applied when this type of work needed to be performed, thus providing sufficient mitigation strategies while not having to complete an ICRA process every time.

The other major change within Table 3 is the distinction of when environmental containment units (ECUs) can be used and when staff are required to always wear coveralls, which are the main differences between Class IV and V. The team decided to allow ECUs for Class IV activities but not in Class V, and to require coveralls in Class V activities.

A final change for Table 3 is the addition of two clarifying notes by the team. These notes state when an infection control permit and approval is to be required and the assignment of class of precautions categories for environmental conditions such as sewage, mold or asbestos, which will require a Class IV precaution for low- and medium-risk groups and a Class V precaution for high- and highest-risk groups.

Among other changes, “Table 4 – Surrounding Area Assessment” has been added to the revised ICRA. This table provides clarifying assessment considerations, such as controls for noise, vibration or the impact to other systems. The table also includes some recommended mitigation strategies.

A formatting change is the separation of the activities to be performed upon completion of a project, which was moved from the original “Minimum Required Infection Control Precautions by Class” table into a separate “Table 6 – Minimum Required Infection Control Precautions to be Performed Upon Completion of Work Activity.”

This was added to help clarify the practice of downgrading precautions in Class III, IV and V, which tend to go through stages of downgrades as work progresses throughout a project. This was never addressed in the original ICRA and allows for a more practical approach than maintaining all of the ICRA precautions throughout the entire life of a project, which was never the intention.

A final addition is the development of an ICRA process guide. The ASHE ICRA 2.0 team felt strongly that developing a guide on how the ICRA should be implemented was vital because many team members have witnessed the improper application of ICRAs.

While the ICRA document is significant, many of the misapplications witnessed stem from a lack of understanding regarding the intent behind the ICRA. The newly developed process guide helps to provide this intent and offer expanded information regarding how to properly implement the ICRA process in health care facilities.

Always evolving

The development of risk assessments for infection control during health care facility design, construction and operations continues to evolve.

The improvements embodied in the ASHE-led ICRA 2.0 document represent the newest iteration in this important and still-developing area of health care facilities management.

Jonathan Flannery, MHSA, CHFM, FASHE, FACHE, is senior associate director of advocacy at the American Society for Health Care Engineering. He can be reached at jflannery@aha.org.