IAHSS updates design guidelines

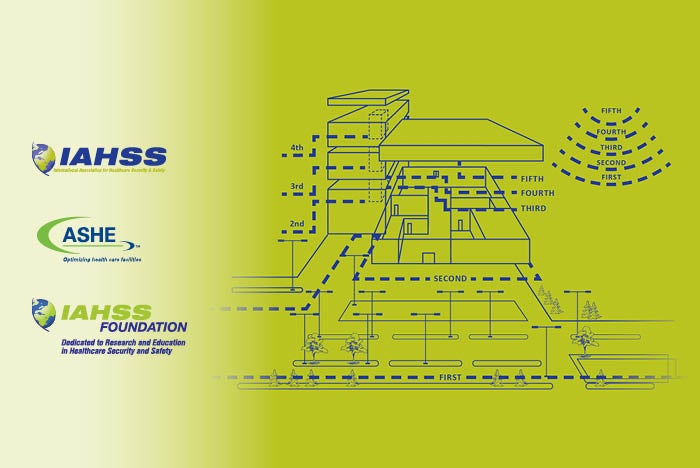

The SDGHF cover diagram shows concentric rings of control and protection.

Graphics repurposed from Security Design Guidelines for Healthcare Facilities

Aggressive and disruptive behavior is on the rise across every facet of health care in the U.S., from hospitals large and small, to residential long-term care facilities, to stand-alone ambulatory surgery centers and orthopedic care sites, to home health and hospice.

The physical environment is often listed as a contributing cause of security incidents as reported by The Joint Commission. In fact, data on sentinel events collected between 2004 and 2012 show that the physical environment is listed as a contributing factor in 80% of abductions, 65% of elopements, 47% of hospital suicides and 35% of other criminal events.

In 2014, the health care field’s most widely recognized guidance for planning, designing and constructing health care and residential health, care, and support facilities, the Facility Guidelines Institute’s Guidelines, began requiring a safety risk assessment (SRA). The SRA includes a risk-identification process, with considerations for infection control, patient handling, falls, medication safety, psychiatric injury, immobility and security.

The purpose of the SRA requirement is to help foster a proactive approach to patient and caregiver safety by mitigating risks from the physical environment that could directly or indirectly contribute to harm.

Updated guidelines

The International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety in June 2020 published the third edition of the Security Design Guidelines for Healthcare Facilities (SDGHF), in collaboration with the American Society for Health Care Engineering.

This edition was developed using the expertise of a multidisciplinary team of subject matter experts to update and develop new guidance for emerging areas within the health care environment, including stand-alone emergency departments (EDs), urgent care and ambulatory surgical care facilities, residential long-term care facilities, and ED-based behavioral health facilities.

These guidelines are intended to assist security practitioners, design professionals, building owner representatives and planning leaders in making informed decisions related to application of proven and effective security principles into each new construction and renovation project. By reasonably addressing security vulnerabilities and risks upfront and early on during design, health care organizations can cost-effectively address the safety and security of new or renovated space.

Following is a brief overview of each segment, pointing out key sections and new features in the latest edition of the SDGHF:

General guideline. This section lays the foundational security design principles that are carried throughout the remaining guidelines. It establishes the principles of risk assessment and crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) that provide a layers of protection approach. Guidance provided lays out the expectation for the inclusion of an assigned project security representative and the importance of a security vulnerability assessment led by a qualified security professional. This important step helps best address security risks upfront and early during design. All succeeding sections complement the security design elements in the general guideline.

Parking and the external campus. This guideline complements the general section through expansion of principles relating to CPTED and establishment of the first ring of protection at the property line. Additional concepts that receive elaboration include the use of physical barriers; coordination of vehicle entrances; landscaping and pedestrian walkways; surveillance and lighting systems; and wayfinding and access control principles.

Buildings and the internal environment. With nine subguidelines, this section is the most voluminous and defines zones of protection within the internal environment; management of access systems; and areas requiring special security consideration such as research facilities, shipping and receiving, mailrooms and administrative office facilities.

Subguidelines within the buildings and the internal environment guidelines largely concentrate on locations of higher risk whose function or activity presents a significant potential for injury, abduction or security loss. They include the following:

- Inpatient facilities. This guideline complements the earlier guidelines by further elaborating the concepts of protection in layers, including zones, control points, circulation routes and required egress paths. Major points of emphasis for this guideline include placement of elevators and stairwells to avoid conflicts between life safety and security. It also features design considerations for reception areas, information desks, and other customer service or screening stations.

- Emergency department. The ED should be viewed as a secured area providing an added layer of protection between the health care facility, public areas and treatment areas. Detailed elements of this guideline include recommendations concerning adjacent spaces, parking, and a distinction between internal and external ambulatory and nonambulatory access points. Many EDs across North America have developed or are developing secure areas where specialized security protocols are required for higher-risk patient populations or those who may pose a security threat. To help address safety in these spaces, the SDGHF task force developed guidance for three areas, including high-risk patient observation rooms, locked emergency psychiatric sections (may also be referred to as “crisis intake centers”), and forensic (i.e., prisoner) patient rooms. Additionally, important guidance is provided specifically for patient care areas, including the safe and smart design of nurses’ stations, triage and other public-facing workstations, as well as waiting rooms serving the organization and care needs of higher security risk patients. The reception or unit clerk desk is a great example: There should be clear distinction from the waiting area, and it should be protected with a design that prevents unwanted access and be of sufficient height, strength and depth to make it difficult for someone to jump over the desk or assault an employee.

- Behavioral/mental health areas. Behavioral/mental health (BMH) patients pose unique challenges and risks because of their medical condition. The BMH guideline provides guidance for stand-alone facilities and units within larger medical complexes. It offers detailed recommendations relating to perimeter design, internal space and ligature-resistant considerations, as well as safety and security systems that protect the privacy, dignity and health of patients. Risks of patient elopement and harm to self and others are a focal point of the guideline.

- Pharmacies. The design of pharmacies should address the unique risks presented by the storage and distribution of narcotics and other controlled substances. The design should create a secure physical separation between pharmacy operations and the public while integrating security systems for access and audit functions. Specific intents within this guideline provide recommendations concerning physical security, protection of people and audit capabilities with considerations for associated medication distribution points, subpharmacies, medication rooms and off-site pharmacies.

- Cashiers and cash collection areas. The collection, storage and handling of cash present unique security risks to health care facilities. Security design considerations for primary and secondary cash collection areas should integrate the physical location and layout with security controls and technology. The risks posed by cash collection primarily involve robbery and internal theft. This guideline provides specific measures covering safes, physical security, video surveillance measures and internal control audits with emphasis on primary cashier areas and other locations where cash transactions occur.

- Infant and pediatric facilities. Infants and pediatric patients are vulnerable patient populations requiring added security measures and special attention when designing safe and secure care environments. Design team members should consider the patient and family experience, the physical location and layout, and integration of security controls and technology. This guideline provides recommendations for reception and waiting areas, access control zones, circulation routes, physical security and technology. Other special areas of consideration include security elements for the new-mother rooms, infant monitoring and pediatric play areas, as well as designated overflow and VIP care.

- Areas with protected health information. Guarding protected health information is an important element of any health facility renovation or new construction project. Designs should address the multiple ways in which privileged information could be compromised and should protect that information by utilizing integrated physical and electronic security systems. This guideline relates to signage, registration areas, furnishings, equipment locations, video surveillance and waste.

- Utility, mechanical and infrastructure areas. The design of utility, mechanical and infrastructure-related space should include the recognition that such space and the mechanical, electrical, plumbing and information technology systems within it are critical assets for the facility. This guideline is intended to provide recommended security design elements for utility systems, mechanical and infrastructure spaces, and built-in redundancy and expansion capabilities pertaining to technology and mechanical systems.

- Biological, chemical and radiation areas. Health care facilities should address the unique security risks presented by highly hazardous materials including, but not limited to, biological, chemical and radioactive materials. This guideline provides recommended design elements covering spaces to be addressed, waste streams, emergency response and audit of materials.

Residential/long-term care. This is a completely new section. Design features for residential/long-term care facilities can be particularly challenging due to the risk of resident wandering, elopement, and resident-on-resident and resident-on-staff violence. Resident mental acuity can be variable because of several factors. Maintaining resident’s privacy and dignity while addressing the potential risks is the challenge. The residential/long-term care design guideline identifies features that can reduce the likelihood of these incidents.

Emergency management. The final major area of emphasis is emergency management. This section recommends health facility designers consider practices that allow for flexibility and resilience required to manage emergency events that negatively impact the delivery of care.

An all-hazards approach to design should be applied to help the facility prepare for, respond to and recover from human-made events and natural disasters alike. This guideline provides recommendations relating to designs that support sheltering in place and repurposing space during emergency operations to accommodate intake and care of a surge of patients.

Designs should facilitate alternative points of access, space reassignment, emergency access to technology infrastructure, a lockdown of spaces and designation of space to provide services to support large numbers of individuals in areas separate from patient care and emergency management.

Avoiding costly changes

A qualified health care security professional can explain the potential security risks in the environment and collaborate with the group about how security can be addressed while still preserving functionality and aesthetics.

The goal is not to create a hardened security state but to create a functioning, aesthetically pleasing and reasonably secure space. Once this is fully understood and grasped, the principles outlined in the SDGHF are much easier to comprehend and deploy.

A principle embedded in the guidance document is to prevent security flaws from being designed into a project — ideally, to minimize expensive change orders and undesirable retrofitting. Retrofitted security features are almost always more obvious and less effective than security features designed into the facility at the early stages.

Additionally, there are some instances when it is nearly impossible to alter a design after the fact due to conflicts with local building and life safety codes or cost-prohibitive retrofitting expenses. Not to mention, add-on security features often take away from the desired look and feel of the new project.

Significant impact

With the tremendous amount of health care construction and renovation under way, the principles of safe hospital design can be readily built into every health care facility project.

By addressing potential security vulnerabilities and risks upfront in the planning and design phases, organizations can have a significant impact on the safety of staff, patients and visitors alike, as well as the ability to better and more efficiently protect the assets of their new capital investments.

About the SDGHF reference

The third edition of the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety’s Security Design Guidelines for Healthcare Facilities was developed in collaboration with the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE).

It used the original methodology established for the first edition that included the expertise of a multidisciplinary team of subject matter experts to update and develop new guidance for emerging areas within the health care environment, including stand-alone emergency departments (EDs), urgent care and surgical care facilities, residential long-term care facilities and ED-based behavioral health facilities.

ASHE members can purchase the 71-page reference by by visiting the ASHE website.

SDGHF task force members and subject matter reviewers

The International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety (IAHSS) is indebted to the original Security Design Guidelines for Healthcare Facilities (SDGHF) task force members and to the subsequent review and revision teams for the second edition and, now, the third edition in 2020.

Members of the 2020 SDGHF task force included:

- Tom Smith, CHPA, CPP — current chair and original SDGHF task force chair; former chair and current member of the IAHSS council on guidelines (CoG); past president of IAHSS; and president of Healthcare Security Consultants Inc.

- Tony York, CHPA, CPP – original SDGHF task force member; former chair and current member of the CoG; past president of IAHSS; co-author of Hospital & Healthcare Security; and executive vice president for health care at Paladin Security Group.

- Don MacAlister, CHPA — original SDGHF task force member; past CoG member; and co-author of Hospital & Healthcare Security.

- Dan Yaross, CHPA, CPP – past CoG vice chair; IAHSS board of directors member; and director of protective services at Nationwide Children’s Hospital.

- Randy Atlas, Ph.D., FAIA, CPP – president of Atlas Safety & Security Design Inc.; and author of 21st Century Security and Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design, second edition.

- Chad E. Beebe, AIA, CHFM, CFPS, CBO, FASHE – deputy executive director of the American Society for Health Care Engineering (ASHE).

- Mike Lauer – CoG member; executive director of support services and corporate public safety at BJC Healthcare and Barnes Jewish Hospital.

- Dave Brown, CHPA, CPP – current CoG chair; executive director on integrated protection services: Fraser Health, Vancouver Coastal Health, Providence Health and Provincial Health Services.

Subject matter expert reviewers included:

- Kevin Tuohey, CHPA – original SDGHF task force member; former chair and member of the CoG; past president of IAHSS; and chief safety officer of the National Emerging Infectious Disease Laboratories at Boston University.

- Paul Sarnese, CHPA – IAHSS president-elect; board liaison to the CoG; and assistant vice president of safety, security and emergency management at Virtua Health.

- Roger Rueda, PSP – IAHSS representative on 2022 Health Guidelines Revision Committee for the Facility Guidelines Institute’s (FGI’s) Guidelines; ad hoc member of the CoG; and associate vice president of security consulting at AECOM.

- Ed Browne, CHFM, CHC, CLSS, FASHE, FACHE – IAHSS representative on 2022 Health Guidelines Revision Committee for FGI’s Guidelines; ad hoc member of IAHSS council on affiliations; ASHE Region 1 board member; and environment of care consultant at Joint Commission Resources Inc.

- Jim Kendig – field director of surveyor management and support for the division of accreditation and certification operations at The Joint Commission.

- Katie Subbotina, MDEM – director of global risk consulting at Paladin Risk Solutions Inc.

Thomas A. Smith, CHPA, CPP, is president and lead consultant at Healthcare Security Consultants Inc., headquartered in Chapel Hill, N.C., and chair of the IAHSS’s SDGHF task force. He can be contacted via email at tomsmith@healthcaresecurityconsultants.com.