How to employ evidence-based design strategies

The new patient room design for the Cleveland Clinic Foundation’s Avon Hospital focused on improving the patient experience by emphasizing safety, leveraging technology and shortening length of stay.

Evidence-based design (EBD) is used in every aspect of daily architectural practice ranging from a request-for-quotation response to selecting the finish for a countertop.

Technology is advancing at a logarithmic rate, and the practice of EBD is adding to this exponential growth. While the value of EBD is clear, consideration should be given to how project teams incorporate it into the normative planning process.

To achieve the best outcome, the design team and health care organization should come to a consensus as to how to leverage EBD into the requirements of the program, schedule and budget.

Engaging the team

For most projects, the health care organization engages architectural and construction professionals. Commonly employed delivery methods include integrated project delivery, construction manager at risk — Lean, and using the “big-room” concept.

The common thread among these methodologies is the importance of teamwork and communication. This means having the right players in the right positions working as a team to perform to their highest capability — all while being on the same page with their teammates.

Every great team has a great coaching staff. This includes leaders to define the mission, establish a game plan and create an environment in which success can grow and flourish. Is there any difference in the business of planning, designing, constructing and occupying health care facilities?

For most health care organizations, selecting a team means searching for professionals who will deliver a cutting-edge facility. To support this goal, it is imperative to assemble a project team that can leverage its collective experience and understanding of innovative research and best practices. Sharing and incorporating this information throughout all phases of design requires visionary thinking and the ability to communicate this vision to garner the support of the health care organization.

The team should include designers, constructors, users, patients, advocacy groups, caregivers, support services professionals, the C-suite, facilities operations and general support services. While the mission and objectives may come from the top down, input from these core user groups needs to be incorporated into any successful design solution.

The value proposition

The most discouraging phrase to hear at the outset of any planning effort is, “We need to do it this way, because we have always done it this way.” Unfortunately, the design profession may have itself to blame for such a response. In many cases, caregivers, administrators and patients have been force-fed the latest fashion and have been left to live with the outcome.

You may also like |

| D. Kirk Hamilton on current and future health care design |

| Accreditation and certification demonstrate EBD expertise |

| Jocelyn Stroupe on interior design and patient outcomes |

|

|

As much as the design profession may take an affront to this attitude, architects should ask themselves if they are recommending a specific approach because they are the experts and have always done it this way. Architects need to challenge themselves to create a value proposition that encourages a forum to explore and validate an approach that truly serves the requirements of everyone invested in the design.

The value proposition is an idea couched in broad-based, independent accreditation of a concept. It positively impacts the quality of the improvements for the patient, caregiver and operations. Having the facility’s return on investment in mind should overlay these solutions. The value proposition can come from any team member and is vetted by the team. As well-meaning, prepared and equipped as any team may be, validating a new approach can be a challenge.

To address this concern, the team can validate a recommended approach through an independent and unbiased analysis of multiple options. These options can be tested through a controlled experiment with objective criteria. Recognizing that this skill set does not reside within an architect’s training, this evaluation should be performed by a qualified environmental psychologist with a doctoral degree. While most midsized architecture and engineering firms cannot cover the overhead of such a position, this should not limit them from recommending and retaining this skill set on a consulting basis.

Patient room example

This situation presented itself during a construction and renovation project that added the Cleveland Clinic Foundation’s Avon Hospital 126-bed inpatient tower to a greenfield site adjacent to the clinic’s Richard E. Jacobs Health Center, with a user team assembled from multiple locations and varying inpatient environments.

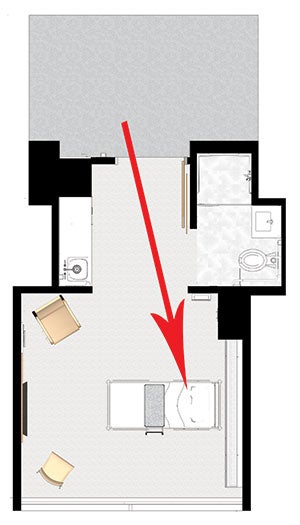

The Avon Hospital’s same-handed patient room configuration allows for easier rounds with a consistent view of patients’ heads.

A vision team had been established early in the project. Considering the substantial investment being undertaken, the times the room would be replicated and opportunity for innovation, the team and the health system’s director of planning recognized the need to retain an environmental psychologist and design researcher to support the efforts.

As with any experiment, defining the objectives and desired data related to a specific modality is Step 1. The project determined to focus on the inpatient room configuration. Working with the design research team, the project team settled on the following avenues to support the design:

- Review the scientific literature. This was done to leverage the large body of EBD information that exists for single-occupancy inpatient rooms. Scientific literature research provided assessment, validation of relevance and possible applications. This exercise dispelled opinions and confirmed best practices and theories that may be more anecdotal than scientific.

- Identify participants for mock-up rooms and surveys. More than 1,800 individuals participated in the mock-up room experiments and patient advocacy process. This included patients, patient advocacy groups, physicians, nurses, patient support services and facility support staff.

- Test mock-up room layout options with a self-report questionnaire. Two rounds of full-scale mock-up rooms were employed during this process. The first round focused on a comparison of same-handed rooms vs. mirrored rooms. Due to the scientific literature findings, site constraints and a desire to maximize patient visibility to the surrounding woodland environment, including daylight for patients, an inboard toilet room configuration was selected. The mock-up rooms were constructed to permit the flipping of the room configuration and entrance, nurse workstation location, bathroom door location and headwalls. After the review of each configuration, participants completed a self-report questionnaire about their observations.

- Explore mock-up room appointments and detail. Once a same-handed room configuration was selected, a mock-up was constructed that evaluated lighting configurations, footwall design, furnishing selections and related colors. For clinical staff, the mock-up also was used to determine fixed computer charting locations vs. movable computer stations. Following the review of each configuration, participants completed a survey about their observations.

- Conduct patient advocacy surveys. In addition to the mock-up experiments, an online patient panel questionnaire was used to conduct an experiment. Hundreds of patients randomly were assigned to assess inpatient unit footwall renderings and furnishings.

- Conduct post-occupancy evaluations of existing medical-surgical units. A post-occupancy evaluation (P-O-E) of an existing Cleveland Clinic inpatient facility’s med-surg rooms involved self-report questionnaires administered to patients and behavioral observations. The existing health care facility had 108 rooms in a mirrored, midboard (or nested) toilet configuration over three floors.

Several goals were defined for the patient room design that focused on improving the patient experience by emphasizing safety, leveraging technology and shortening length of stay. Considerations from caregivers regarding safety, quality and efficiency also had to be embodied into the design. Not only did these objectives refine the design goals for the patient rooms, but they also defined clear objectives for the research team to illustrate, test, measure and validate.

Research led to the decision that patient charting would be done on workstations on wheels that would remain in the patient room.

On this fast-track project, the design was developed and the mock-up experiments occurred simultaneously while site work and foundation construction were underway. Implementing the experiment required broad-based involvement from all team members.

The design research team led the way by defining the experiments and P-O-E. The project management team procured available space and resources to enable the mock-up location. In collaboration with the users, the design team developed concepts for evaluation, including multiple options for the changeability of the mock-up. The construction management team worked with subcontractors to construct the mock-up rooms and provide on-site assistance in changing out the mock-up rooms during the course of a day.

The report of findings ran parallel to design delivery so details could be refined just in time. In a similar way, lighting options, fixture selection and other design issues that had cost impacts were evaluated during the design development phase with the second round of mock-up experiments. The significant advantage of the timing was the ability to make informed decisions, based not only on cost, design preference and user consideration, but also on the quantifiable impact of design on patients and care providers.

Meta-synthesis agglomerates data from scientific studies and real project parameters such as organizational culture, site, budget and schedule. It is a process that enables design researchers to identify a specific research question and then search for, select, appraise, summarize and combine scientific evidence and project parameters to address the research question. The findings and data had a direct impact on the design recommendations that the team jointly advanced.

The top five factors influencing patient experience were the quality of the room, the ability to act, bedside control, bedside lighting and bathroom lighting. The team discovered that the lack of control had a negative impact on the patients’ feelings. They felt loss of autonomy and that they were burdening others when asking permission to do things. This issue was addressed through a patient-pillow device that allowed for control of lighting, room temperature and the smart TV. Other details that were evaluated and supported a greater sense of comfort and quality of care included light fixture selection, quantity and placement; artwork; furnishings; and colors.

The same-handed patient room configuration allowed for easier rounds with a consistent view of patients’ heads. It improved ease of patient approach and transfer. It supported consistency in location of headwall outlets and switches, and provided easier access to nurse servers.

It was determined that patient charting would be done on workstations on wheels that would remain in the patient room. By employing a tap-and-go process of login, caregivers could securely access patient records immediately as they moved from room to room. It also was determined that the patient bathroom would be accessed through a sliding door that faced the nurse workstation as opposed to the bed.

The process of engaging a researcher and using experimentation during the design taught the team several lessons. It discovered that value-added extends far beyond the quantitative benefits to qualitative outcomes that could not be predicted. For the project team, the process gave members an opportunity to rethink how they practice.

This opportunity to engage and expand the collaboration with the patients, patient advocacy groups and families was unprecedented. In an era of heightened awareness about improving the patient experience, the opportunity to involve these groups was invaluable.

For the design and user teams, the process of testing and evaluating findings created a deeper sense of shared decision-making, not based on individual preferences or position but on data that led to a collective understanding and ownership of the design. The relationships developed through this process of shared consensus were deepened and rewarded equally as the mission was achieved.

Because of the success of the process, the health care organization is marshaling a follow-up study to keep the team intact as it engages a P-O-E of the new hospital this year.

Fully engaged team

Key to a successful EBD project is assembling fully engaged team members who can work together to achieve the design project’s overarching goals.

Philip LiBassi, FAIA, FACHA, is senior principal at DLR Group|Westlake Reed Leskosky. He can be reached at plibassi@dlrgroup.com. Supporting information was provided by EwingCole’s Nicholas Watkins, Ph.D., director of research, and Esperanza Harper, EDAC, health care planner.