2015 Salary Survey results

Despite the slowly recovering economy and sea of health care policy changes implemented in recent years, salaries continue to rise for Health Facilities Management (HFM) readers — some modestly and others by more substantial margins.

While pay for facilities and construction managers has shown healthy increases since 2012, compensation for environmental services managers showed a big leap — a jump experts say could be tied to health care’s increasing focus on infection control and patient satisfaction and an overall increase in key job responsibilities.

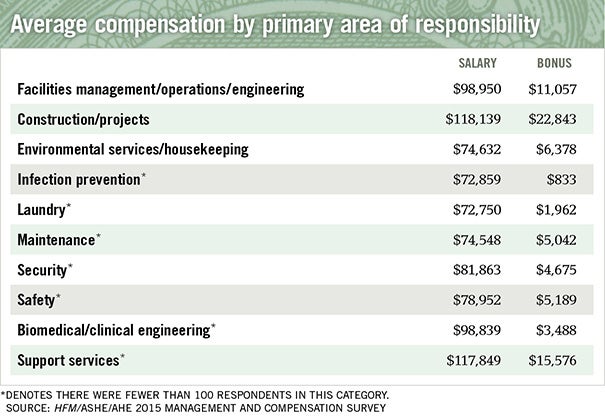

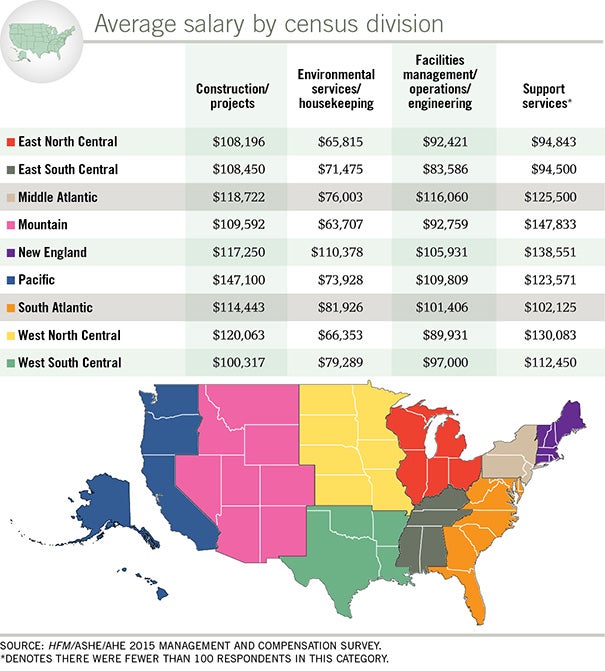

Between 2012 and 2015, environmental services/housekeeping increased 8.0 percent to $74,632, while construction/project management rose 5.3 percent to an average $118,139, and facilities management/operations/engineering increased by 3.4 percent to $98,950. These figures are based on a survey of management compensation conducted by HFM in cooperation with the American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE) and the Association for the Healthcare Environment (AHE).

The average salary stretching across a variety of job categories encompassed by the survey has risen from $90,659 in 2012 to $95,873 in 2015 — an increase of 5.8 percent over 3 years or 1.9 percent annually.

The online survey was conducted in March and April among health care organizations and members of ASHE and AHE. A total of 1,772 people responded, making for an overall margin of error of plus or minus 5 percent.

By contrast, the last HFM survey, which covered 2009 to 2012, showed that environmental services managers were at the bottom of the totem pole, averaging a 2 percent raise to $69,111, while construction managers’ salaries increased 7 percent to an average of $112,190 and facilities managers’ pay rose by 4 percent to $95,698.

Dramatic changes

The 2015 numbers may be tied in part to the dramatic changes many hospitals are undergoing on a number of fronts. More than a third of those surveyed work in organizations that have been involved in mergers and consolidations, which often means a reduction in directors/managers, leaving remaining staff to absorb those job duties. For environmental services managers, at least, the increasing workload seems to have translated into modest increases in salaries to compensate for the duty increase, says Patti Costello, executive director of AHE. “We hope this trend continues in an effort to retain the best environmental services leadership.”

“It appears some organizations are better compensating environmental services for assuming a larger role,” Costello continues. “We are seeing managers taking on responsibilities for food service, transport, safety, security and many other areas directly linked to patient satisfaction, and many are also responsible for more than one campus.

You may also like |

| 2012 Salary Survey results |

| Succession planning for facilities managers |

| Making the case for infrastructure funding |

| |

“However, it remains apparent environmental services still lags behind other disciplines when it comes to compensation,” she adds. “With better reporting of environmental services metrics, we hope to see that change.”

One expert describes the environmental services surge as a “catching-up” period. “Environmental services is what facilities management was like 10 to 15 years ago,” says Jack Gosselin, FASHE, CHFM, a former hospital facilities manager who runs a Mystic, Conn.-based recruiting firm. “Environmental services is playing a much bigger role with the patient experience, infection control and facility image … . Organizations are appreciating the value of good environmental leadership.”

Construction and facilities management increases are above the average rate of inflation and will continue to increase in tandem with the significant responsibility added to their roles, says Dale Woodin, senior executive director, ASHE. Performance metrics will become even more critical to salaries and bonuses, he adds. “Performance metrics are an area where facilities managers can move the needle and really identify aggressive goals, share them with leadership and hit these goals,” Woodin says.

“Our members have the dual responsibility of maintaining an optimal environment for patients and staff that meets all of the regulatory requirements, while also identifying opportunities to reduce their costs in an effort to better support patient care. This could be the reason we are seeing more hospitals recruit Certified Healthcare Facility Managers (CHFMs) to manage their facilities, which could be a driver of the modest 3.4 percent salary increase between 2012 and 2015,” adds Patrick Andrus, CAE, deputy executive director, operations, ASHE.

Hospitals continue to reward those professional certifications, including CHFM and Certified Healthcare Environmental Services Professional (CHESP), with higher salaries, the survey shows (see sidebar, Page 23). Other trends include a significant “graying” of the facilities professional worker and a growing connection between bonuses and performance metrics/HCAHPS scores.

Taking on more

Whether or not they are being compensated for it, managers across the board are being asked to take on more responsibility. Forty-seven percent of respondents reported having added responsibilities as a result of a merger or acquisition while just 12 percent received a salary increase. One survey respondent summed it up this way: “Increased responsibility, no salary increase, title change.”

Ten percent said they have less decision-making authority and that more decisions are handed down from the corporate level — a change driven by centralization that has resulted in what Woodin calls “title deflation” for facilities managers. “You used to have a facility manager, now you have a facility supervisor,” he says.

“This is good for centralization, but it takes away some of the job enjoyment that comes from making decisions locally,” adds LaMar Davis, CHSP, CHFM, CHC, deputy administrator of facilities planning, design and construction, Access Community Health Network, Chicago.

Survey respondents also reported a 27 percent increase in the number of departments reporting to them, which Woodin attributes to mergers, belt-tightening and an overall confidence in facilities staff. “It’s like the old saying, ‘the reward for good work is more work.’ ”

Gosselin says facilities managers make strong multidepartment administrators. “The best leaders hospitals have are in the facilities area, so we reward that behavior by giving them support departments.”

For example, Harold Brungard, vice president of facilities and plant operations at Mount Nittany Medical Center, State College, Pa., was assigned culinary and nutrition services and the department of emergency medical services during a reorganization of the facility’s management team two years ago. Brungard saw the change as a logical part of the hospital’s expansion. “It makes sense to promote the team approach within the environment of care,” says Brungard.

Another survey respondent reported “taking over property management including environmental services for 44 medical office buildings in addition to maintenance of the same buildings.”

Because most facilities managers have an engineering background, overseeing departments out of their areas of expertise can be a challenge, Davis says. “But institutions say that we have the skill sets to pick up these areas,” he adds. “So the bump in salary may be based in part on adding other departments and even adding additional hospitals to a facility manager’s job duties.”

To aid its members in taking on new responsibilities, ASHE is extending its educational offerings to encompass support services areas, Davis says.

On the environmental services side, managers are picking up more — and a wider variety of — departments, ranging from patient transport and valet services to the mail room and furniture moving. One survey respondent who was hired as a certified dietary manager was later assigned environmental services and linen services.

The added responsibility shows that administrators have trust in their environmental services leaders, according to Doug Rothermel, CHESP, director of environmental services at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Tampa, Fla. “We’re a 12-hospital system, so it makes sense to consolidate and streamline whenever possible, and rely on the talent of managers and directors who can take on that added responsibility,” he says.

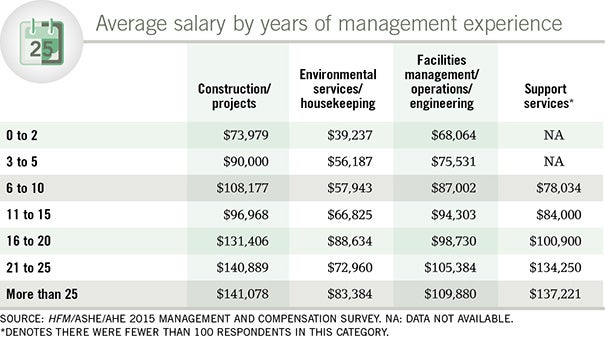

Graying of management

A critical factor destined to leave a huge impact on salaries is the aging of the health care management workforce. The survey shows that 29 percent of respondents have 25 or more years in management/supervision, vs. 26 percent in 2012, while 34 percent have more than 25 years just in health care management, vs. 29 percent in 2012.

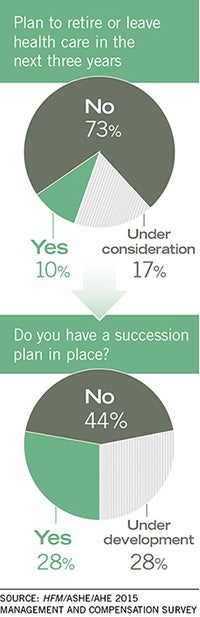

One reason for the surge is fewer retirements. Managers are working longer to compensate for factors including retirement portfolio losses suffered during the recession or to finish projects taken on during the surge of recent mergers. But when baby boomers begin retiring en masse, the industry will suffer “a huge talent drain,” Woodin says. “There’s a huge graying of management, and it’s a major problem.” While the survey shows that 73 percent are not planning to retire in the next three years, when that big wave comes, it could hit facility management hard.

Costello agrees this trend will hit environmental services hard as well. “AHE’s goal is to ensure these managers are replaced with competent, highly skilled, strategically focused professionals,” she says.

For that reason, succession planning — essentially grooming talented people within and outside the facility to fill key vacancies — is critical to a hospital’s planning process, Woodin says. While it has yet to take widespread hold, the survey shows that 28 percent have a succession plan in place and 28 percent have a plan in development.

A key part of the plan is recruiting younger employees, who are in short supply in the health facilities management/environmental services fields. The survey shows that just 5.2 percent of survey respondents are between 25 and 34 years.

“Retirements are already leaving huge gaps and there is no one to fill them,” Davis says. “I know one area hospital that was looking for a facility manager for over a year.”

After seeing the challenges firsthand, Gosselin recommends that hospitals target younger candidates from parallel industries, such as pharmaceutical manufacturing, to ensure a compatible background and transferrable skills. “Decades ago, an engineering degree was necessary, but now a business degree would be appropriate considering that real estate and property management as well as fiscal performance are a big part of the job these days. And you really need the hospital experience.”

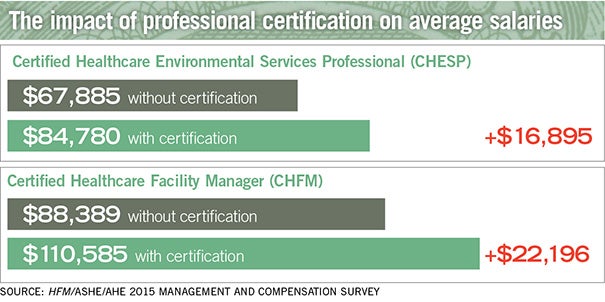

Certification drives health facility salary increases

While professional certification isn’t yet required for most health care management positions, that’s the direction things are headed. And many managers who are certified are already seeing a difference in their paychecks.

Salaries showed a sizable increase for managers who have earned Certified Healthcare Facility Manager (CHFM) or Certified Healthcare Environmental Services Professional (CHESP) designations, according to the recent survey on management compensation conducted by Health Facilities Management, the American Society for Healthcare Engineering (ASHE) and the Association for the Healthcare Environment (AHE).

Facilities managers each year earn an average of $110,585 with a CHFM, and $88,389 without it; ES/housekeeping managers earn $84,780 with a CHESP, and $67,885 annually without it.

While certification isn’t often required for new hires (8.7 percent require a CHFM, 2.6 percent require a Certified Healthcare Constructor, or CHC, certification and 3.4 percent require a CHESP), Dale Woodin, senior executive director, ASHE, says those requirements will expand soon. “You need to have a certified facility manager heading up your operations,” he says. “Certification used to be a pinnacle; now it’s the point of entry.”

Regardless, roughly half of the respondents surveyed reported having no certification, while 25 percent hold CHFM, 8.5 percent have attained CHESP and 4.5 percent hold CHC certificates.

“Those numbers tell me that we as a profession have a lot of work to do in demonstrating the value of those credentials,” says Patti Costello, executive director, AHE. “But I believe those percentages will go up very soon. A lot more employers either prefer or require certification as the price of admission.”

AHE recently announced a new certification curriculum for environmental services technicians, Certified Healthcare Environmental Services Technician (CHEST), that hospitals and other health care facilities can use to train their technicians. “Offering front-line technicians CHEST certification should drive CHESP certification numbers as well,” Costello says.

Anyway you view it, certification can only help a manager’s career, says Doug Rothermel, CHESP, director of environmental services at St. Joseph’s Hospital, Tampa, Fla.

“In my organization, certification sets you apart as someone who goes the extra mile, someone who is a go-getter,” Rothermel says. “When it’s clear that certification is tied to higher salaries, why not pursue it? It’s a win-win.”

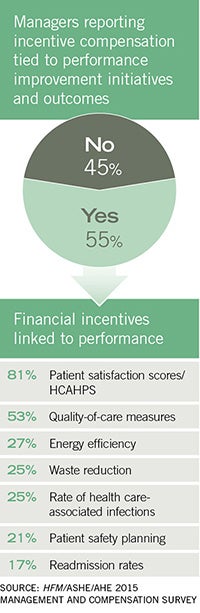

Metrics tied to bonuses

One way to lure good employees is to offer top-level compensation. The survey showed that 35 percent of respondents receive cash bonuses, and that the amounts given most often were $5,000 to $10,000 (24 percent) and $10,000 to $25,000 (also 24 percent) annually. The mean bonus was $12,215, up from a mean of $10,108 in 2012.

Fifty-five percent of respondents say their incentive compensation is tied to performance improvement metrics like patient satisfaction, quality of care and health care-associated infection rates.

“For environmental services managers, infection prevention and patient satisfaction are critical focus areas,” Costello says. “Staff, including the management team, are evaluated and held accountable to quality outcomes the same as the hospitals. Outcomes, whether clinical quality or satisfaction, need to be ingrained into the culture of the entire environmental services department to draw the incentive compensation.”

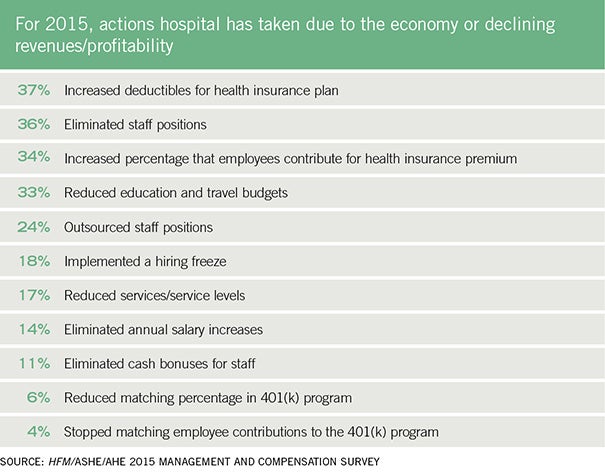

Unfortunately, bonuses are often on the chopping block during cutbacks. The survey shows that 11 percent of hospitals eliminated cash bonuses for staff due to the economy or declining revenues/profitability; 36 percent eliminated staff positions; 37 percent had increases in deductibles for health insurance plans; and 34 percent had increased employee contributions to health insurance.

Another 24 percent cited outsourcing staff positions as a means of cutting costs. As one respondent explained it, “as staff have been cut, outside vendors/contractors have been used to fill those gaps.” But outsourcing is not always the answer. Said one respondent: “It takes time to recruit and build the case for not outsourcing.”

Still, many respondents report no changes, saying their facilities are in a growth pattern. One example: “No reductions. Facility is growing and expanding its services and size.”

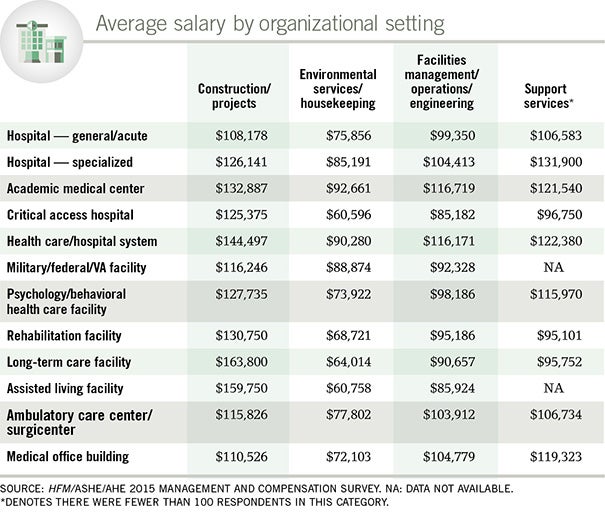

Moving the dial

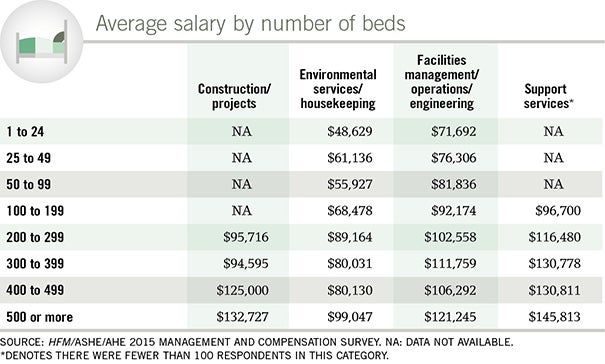

Growth — from supervising duties to salaries — is the wave of the future, Gosselin says. In fact, he is already seeing typical facility managers getting what he calls “dramatic increases in compensation, due to the responsibility increase.” For a midsize (200–400 bed) community hospital, he is seeing salaries in the ballpark of $110,000 to $130,000. “It’s rare to place someone at a director level for less than $100,000,” he says.

Going forward, health facilities managers seeking higher pay/bonuses would be wise to focus on two areas: performance metrics, particularly those tied to patient care, and certification.

While facility managers aren’t connected as directly to day-to-day patient care as environmental services managers, they need to understand the huge role they play, and make sure upper management is aware of their contribution, Woodin says.

“The first challenge is to translate the impact of your role on patient outcomes,” he says. “Ask yourself how you make a difference in terms of impacting patient satisfaction and outcomes. Then set goals and share them with leadership. You’ve got to be your biggest advocate. Leadership’s understanding of how you support the institutional mission ties into a bigger paycheck.”

Beth Burmahl is a freelance writer based in Oak Park, Ill., and former associate editor for Health Facilities Management magazine. Suzanna Hoppszallern is a senior editor of data and research for HFM’s sister publication, Hospitals & Health Networks.