Designing for hospital efficiency

View "Process-oriented designs" gallery

Health care environments can be supportive of efficient care processes, a hindrance to them or something in between. Care delivery models must constantly change to meet the demands of an aging population, a shortage of care providers and new treatment modalities, such as mobile technologies.

Coordination of care to empower patients, improve patient outcomes and reduce readmissions requires robust multidisciplinary care collaboration, both physically and virtually. Healing environments for patients and staff also must incorporate supportive environments for families and care partners.

There are eight health care flows that provide a comprehensive foundation from which inspiring and healing environments can be built.

Spaces and conditions

Health care architects rely on staff input during user group sessions to learn about workflow and processes. However, nurses often do not realize that many tasks they are performing involve workarounds, and staff may try to recreate inefficient current work environments. This input may lead to incremental change, but cannot lead to the innovation necessary to create a paradigm shift in planning and design that truly optimizes the environment to support safe and efficient patient care.

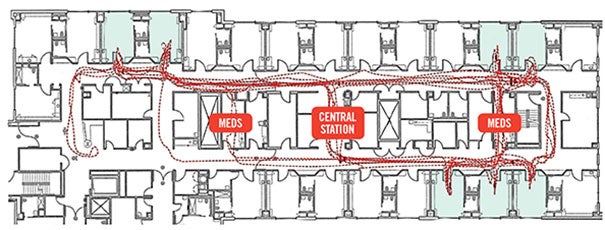

For instance, a spaghetti diagram from a recent shadowing exercise reveals how nurses utilized the medication rooms and central staff work station as circulation paths due to lack of circulation paths in the solid support core [see graphic above]. The disruption created by constant traffic through a central staff work space intended for heads-down and distraction-free work is problematic because it can lead to increased medical errors.

About this article

This feature is one of a series of quarterly articles published by Health Facilities Management in partnership with the American College of Healthcare Architects.

Architects often design nursing units based on pods and neighborhoods to distribute support services. In the facility illustrated in the spaghetti diagram, a nurse on the medical unit was in charge of seven patients distributed throughout the medical unit. There are several reasons why patients are dispersed: They are assigned based on acuity level, nurse skill sets and the desire for continuity of patient care. Daily admissions and discharges also play a significant role.

In fact, nursing units transfer or discharge 40 to 70 percent of their patients every day. Nurses travel greater distances with all-single patient rooms, and are also walking miles to retrieve items necessary for direct patient care. Support spaces often are not standardized, requiring nurses to travel to different areas to retrieve items for care.

Staff work spaces have not changed appreciably over the years. Although the concept of centralized vs. decentralized space is discussed during programming, the design of these areas remains very traditional.

Traditional central stations and decentralized alcoves still are widely utilized. Nurses must walk around the bullpen configurations and tend to chart on the outside, because walking to the inside of the station can add hundreds of steps to an already long travel day.

Linear bar configurations are traditional in the zone between the support core and the circulation path and this configuration adds numerous steps.

Decentralized alcoves have proliferated in nursing unit design over the past few years. Keeping caregivers at the patient room is desirable, but designing that area with a fixed counter and chair creates a single-use space. The ability to utilize that space for other purposes can be achieved if the space is flexible and not built-in. Windows into the patient room from the alcove give nurses a direct view of the patient.

Those same windows also enable direct views of patients by anyone who walks down the hall, compromising patient dignity and confidentiality. This is why blinds are almost always closed. Innovation must be the catalyst to enable a paradigm shift in the planning and design of these crucial spaces to keep nurses close to their patients while maintaining patient dignity and privacy.

This medical unit spaghetti diagram, based on an eight-hour nurse shadowing exercise, shows that staff utilized the medication rooms and central staff work area as travel routes due to a lack of circulation paths through the core of the nursing unit.

Health care flows

Adherence to Lean principles, efficient workflow and the removal of wasteful processes and workarounds is paramount to creating safe, effective and efficient patient care environments. The foundation of Lean rests on the notion that continuous process improvement requires continuous change — driving the need for flexible and adaptive health care environments. Understanding Lean, and wasteful processes inherent in health care, is key to laying the foundation from which to launch innovation in new health care environments.

You may also like |

| Designs to improve patient flow |

| Joint Commission ramps up flow expectations |

| 2014 HFM/ASHE Health Facility Design Survey |

| |

The planning process provides an opportunity for transformational change, while the design process incorporates and embeds the efficient and innovative characteristics necessary to support and sustain future care delivery models. Incorporating Lean and leveraging the eight health care flows into the early stages of the planning process are pivotal to envisioning spaces that are healing, inspirational and efficient. Utilizing these health care flows as a checklist ensures an efficient, human-centered experience for all users.

1 Flow of staff. This involves creating a safe, efficient, calming and attractive health care work environment. Such environments can aid in recruiting and retaining nurses. Front-line nurses are at the center of all patient care delivery, and staffing shortages have a direct effect on patient safety. Inadequate staffing has shown to increase patient mortality and increase the incidence of health care-associated infections. The most effective and efficient team enables all members to practice at the top of their licenses. Tasking nurses with stocking supplies is just one example of taking a highly valued care team member away from direct patient care. Nursing burnout can be attributed to many factors, including workarounds and wasteful processes. Design considerations include decentralized support spaces that aid the act of caregiving. Work space considerations must accommodate a multigenerational workforce and aging caregivers, as well as a variety of work styles, needs and activities. Planning off-stage spaces must incorporate technology to support virtual consultations and collaboration. Off-stage spaces provide staff with a secluded place for respite, even if only briefly, to recharge the spirit, rejuvenate the body, and replenish the soul — important aspects that also support recruitment and retention.

2 Flow of patients. The focus of patient care has centered on the patient room, but we also can envision the entire health care environment as a place of healing. Ambulation aids in the healing process, but patients may be reluctant to leave the proximity of their rooms if they do not have a place of respite when away from their rooms. Places of respite encourage and support periodic independent ambulation. Decentralized respite spaces promote patient safety by providing patients with a comfortable seat outside of their rooms. These areas also can be used for goal-setting. Patients can ambulate to more distant places of respite as part of their recovery process. The alcove between every two patient rooms can be used as a “front porch” respite area with comfortable furniture if not designed with fixed, built-in casework. Flexible planning dictates the need for multiuse space versus dedicated space.

3 Flow of families and care partners. Families and care partners are taking on more of the patient care activities that traditionally were part of nursing care. Caring for a loved one 24/7 creates the need for a space that accommodates multiple functions — working, eating and a place of quiet respite. Family zones, which support this need, traditionally have been designed near the exterior window.

The stress of caring for a loved one can be alleviated by creating a comfortable and healing place for families and care partners. This space can be designed at the footwall to enable families and care partners to remain in proximity to the patient, while enabling the space to be closed off with a curtain from the rest of the room without eliminating the patient’s view of nature. Creating this nest also helps to prevent waking the family and care partner if staff attend to the patient in the middle of the night. A good night’s sleep is as healthy for the family and care partner as it is for the patient. The ability for the family caregivers to close the curtain to watch TV without disturbing the sleeping patient also is beneficial.

4 Flow of information. Information can be categorized in three forms — paper, electronic and verbal. Although paperless environments are the goal, paper still is utilized and must be accommodated and organized. Also, planning spaces that enable the undisturbed and uninterrupted exchange of verbal information reduces medical errors. Technology is pervasive in caregiving activities, creating the need for an environment that supports both fixed and mobile solutions. Leveraging lessons from other vertical markets like education helps to optimize environments for mobile workers in health care environments. Collaboration is crucial to support multidisciplinary teams and consultations that may occur both on-site and via virtual gatherings.

5 Flow of medications. Most medications are stored in decentralized locations within a pod or neighborhood of patient rooms. Even these decentralized locations unnecessarily increase travel distances for nurses. Automated dispensing machines are intended to ensure safety protocols and inventory controls. However, nurses many times perform workarounds with medication administration processes due to travel distances, inefficiencies and having to wait to access the medication dispensing machine. Bar code technology is intended to be a safety net for safe patient medication administration, but this strategy does not always work due to wireless dead spots.

Processes and environments must be designed to place routine patient medication at the point of use. This will help to remove reliance on faulty human behaviors, avoid the need for backup processes that do not always work and ensure patient safety.

Architects can design environments that encourage staff to do the right thing by bringing patients’ routine medications closer to the point of care to minimize the potential for a medication error.

6 Flow of supplies. Hoarding is a huge red flag that the supply distribution process is not working. At times, nurses hoard supplies because they are not always confident that they will have what they need where and when they need it, and they worry that patient care will be compromised. Locating supplies at the point of use reduces hunting and gathering, and shortens staff travel distances. One solution is to triage supplies to place the majority of frequently used supplies at the patient room with backup supplies located in decentralized places throughout the unit. Mobile carts for supply storage provide the most planning flexibility and eliminate unsafe ergonomic conditions of having staff attempt to get supplies in upper cabinets that are out of reach.

7 Flow of equipment. Health care environments present unlimited opportunities to improve processes and prevent the spread of pathogens. For instance, when a piece of equipment is removed from a patient room, the potential exists for patient equipment to be contaminated. Moving potentially contaminated equipment throughout the hospital could be averted by cleaning select pieces of equipment along with other items in the patient room. Equipment program requirements are now greater with an older and more acutely ill patient population. IV poles and pumps are standard equipment items for the sicker patients who now occupy inpatient beds; commodes for patients who cannot walk to the bathroom are common; and walk devices are necessary for aging baby boomers. Designing a small storage space adjacent to the patient room, much like storage spaces designed for labor, delivery and recovery rooms are now necessary to accommodate the equipment needed for today’s older and sicker patient population. Likewise, the location of lift equipment determines whether such equipment will be used or ignored by nursing staff.

8 Flow of output. Hospitals generate more than 26 pounds of waste material per staffed bed per day, which must be segregated by type. The process of waste removal requires thoughtful consideration to ensure that adequate space is planned in both the patient room and decentralized soiled holding spaces.

Identifying inefficiencies

All of these influences are driving the need for a paradigm shift in the planning and design of space that will identify and eliminate inefficient processes and workflows.

Health care designers must leverage innovative planning and design concepts to create holistic, healing, efficient and safe environments for all users to create truly human-centered experiences.

Kerrie Cardon, R.N., is a registered nurse, health care architect and a consultant with Bison Creek Innovations, Whitefish, Mont., and Herb Giffin, AIA, ACHA, is a health care architect and principal with GBJ Architecture, Portland, Ore. They can be reached at kerrie@bisoncreekinnovations.com and herb.giffin@gbjarch.com, respectively.

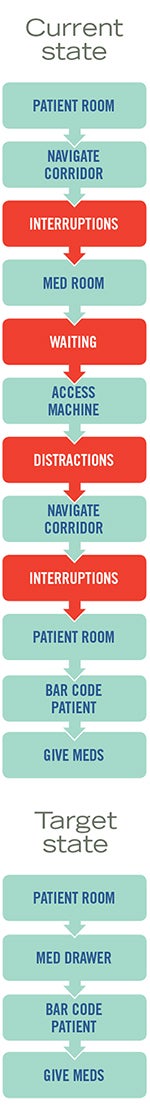

A current-state process map shows places in the process at risk for medication errors while the target-state map keeps medications at the patient room.

Locating medications to help prevent errors

Nurses access patients’ medications several times throughout a shift, and automated dispensing machines can create bottlenecks as nurses queue up, waiting to access the machine. Distractions occur in the medication room because nurses interact with each other while waiting for the machine, increasing the potential for errors.

A red-taped area on the floor in front of the machine is one workaround, but nurses still hear conversations in the vicinity. What’s more, once nurses access the machine, they may be tempted to pull all patients’ medications scheduled at the same time, but this shortcut could result in additional medication errors. Fluorescent sashes used as a “do not disturb” visual signal during medication administration are another example of a workaround. Workarounds are indications that the medication administration process must be improved.

Medication interruptions impact cognitive work and frequently occur as nurses travel from the medication room to a patient’s room. A medication study found direct correlation between interruptions and medication errors. Bar code technology has been adopted to increase patient safety; however, relying on technology as a safety net does not always work due to wireless dead spots.

Physical spaces that embed safe processes into the design by decentralizing routine patient medications in a “no-interruption zone” at the patient room eliminate waiting for automated medication dispensing machine access; reduce nurse travel distances; avoid the waste of hunting and gathering as well as the need to create workarounds; eliminate the need to rely solely on technology to prevent injuries; create an efficient environment that promotes staff retention; and increase patient safety.

Decentralizing medications to the point of use at the patient room can reduce errors by eliminating interruptions, travel distances and wasteful processes.

Work environments to support Lean operations

The central workstation historically was used for charting and social interaction, which made the workstations lively and noisy. The move from centralized to decentralized charting has placed nurses closer to patients, but has left them feeling isolated.

While decentralized alcoves between two patient rooms have become prevalent in recent years, the fixed, built-in counter creates spaces that are underutilized because they are not flexible, ergonomic or adjustable; nor do they accommodate alternate forms of technology, such as workstations on wheels. Additionally, the space between the support core and circulation traditionally has been designed using long, linear bar configurations that add staff steps.

Changes in technology have altered the way staff members handle information. Wireless technology allows staff to document in spaces that support their respective work patterns and styles. Leveraging planning strategies utilized by educational environments supports the approaches needed for the multidisciplinary collaborative spaces.

Work environments must support many competing needs and complex issues, such as the different work styles and preferences of a multigenerational workforce. Visibility and openness must be balanced with privacy and confidentiality. Environments must be free from distraction, while also supporting the need for socialization and camaraderie. Collaboration includes both physical congregation and virtual connections.

Multiuse workstations are approachable and technology-enabled. Flexible and adaptable spaces support Lean operations and the ability to be reconfigured for continuous process improvement. On-stage spaces are exposed and active, while off-stage spaces are reflective, support uninterrupted work and create a place of staff respite.

Designers should envision space as a blank canvas and craft the staff work environment through an innovative lens. To the extent possible, they should plan an open-core concept to maximize flexibility and reconfiguration potential. Modular solutions should be applied to accommodate the competing needs, complex issues, functions and workflow processes necessary for efficient and effective work.

Need more information on designing health care spaces for optimal flow?

Try the following resources used by the authors in preparing this article:

• Pallarito, K. "Interrupting a Nurse Makes Medication Errors More Likely." HealthDay, April 26, 2010.

• Hendrich, A.; Fay, J; Sorrells A. "Effects of Acuity-Adaptable Rooms on Flow of Patients and Delivery of Care." American Journal of Critical Care, January 2004, Vol. 31, No. 1

• "Why are those nurses hogging so much of the hospital budget?!" March 25, 2011.

• Cimiotti, J. "How Nurse Burnout Affects Hospital-Acquired Infections." Physicians Weekly, Feb. 20, 2014.

• Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. "Wisdom at Work: The Importance of the Older and Experienced Nurse in the Workplace," June 2006.

• Iyer, Pat. "Preoccupation, Interruptions & Multitasking Lead to Medical Errors." Medical-Legal Topics, Dec. 2, 2014.

•"Hospital Bar Codes not a Perfect Rx." Philadelphia Inquirer, July 1, 2008.

•"To Err is Human." Institute of Medicine, 2006.

• Eldlich, Richard F.; Winters, Kathryne L.; Hudson, Mary Anne; Britt, L.D.; Long, William B. "Prevention of disabling back injuries in nurses by the use of mechanical patient lift systems," Journal of Long-Term Effects of Medical Implants, 2004, Vol. 14, No. 6

• Wadhwa, S. "Connection Between Pollution and Health Care," Sept. 1, 2013, blog post.