Environmental services staffing methodologies

|

| PHOTO BY MICHAEL BURKE Cleaning a hospital’s surgical suite will require much more concentrated work than cleaning the hospital’s administrative office space. |

Staffing is by far the largest expense the environmental services (ES) department incurs, typically accounting for 75–80 percent of total department spending. Given these numbers, it’s clear that staffing has the ability to make or break the financial backbone of the entire departmental budget. No other ES departmental successes will offset failures associated with ineffective staffing.

With the advent of government-assessed, value-based purchasing and its reliance on HCAHPS measurements in determining hospital reimbursements, the ES staffing equation can have an impact on the entire hospital revenue stream. In fact, it is such an integral aspect of the management process that an ES manager would benefit by making this his or her No. 1 priority.

Understanding workload

Too many ES departments base their staffing on nonempirical data and information. They rely on employee feedback, the managers’ gut feelings for workload, an end users’ demand for availability or other non-value-based criteria.

Although there are several ES software programs available to assist managers in building staffing schedules based on workloads and time studies, it is fundamental that a manager understand the process and science associated with the methodology. Part of the process for the Certified Healthcare Environmental Services Professional (CHESP) certification offered to ES managers through the Association for the Healthcare Environment (AHE) is that the manager understand and be able to generate staffing schedules based on established methodologies of the industry.

The core understanding of building staffing capacities in ES is to recognize what constitutes the workload of the staff. There are four factors that need to be plugged into the equation for each staffing position:

Cleanable square footage. Gross square footage refers to all measurable space contained within the walls and under the roof of any individual facility. Cleanable square footage only counts the actual space that the ES staff clean. Consequently, it excludes locations such as electrical or maintenance closets, inner space between walls, courtyards or patios (unless this area is cleaned by the ES department) and parking garages. The engineering or facilities department is typically a good place to acquire this information, as well as to obtain building and floor plans.

Frequency of cleaning. This specifically relates to the number of times an identified location or square footage will be cleaned in a 24-hour period, such as a main lobby or public restroom that is cleaned multiple times throughout the day.

Lock-in areas. This refers to departments or locations to which a housekeeper is assigned for a shift or length of time regardless of square footage or frequency. An example might be in the emergency department (ED), where it’s required to have someone available for cleaning functions no matter the size of the department or volume of patients being seen.

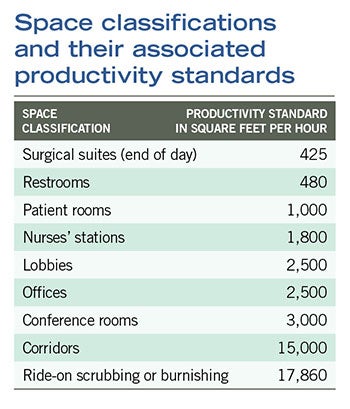

Space classification. This is the identification of space according to its use. Examples of classifications and their associated productivity standards can be viewed in the table on Page 42. Each classification requires a different level of cleaning and time commitment. A terminal cleaning of a surgical suite will require more concentrated cleaning than an office area. Each classification will be assigned its own productivity standard as staffing assignments are developed.

These four categories are not all a manager will need to know to build the department's schedules. However, they are the core workload standards. The four categories will be incorporated into the process of building a workload time study and functioning schedules for departmental staff. Adjustments then are made to the core workload as required.

About this seriesThis series of tutorial articles is a joint project of the Association for the Healthcare Environment and Health Facilities Management. |

Getting started

One of the most challenging aspects of this process will be to identify accurately the cleanable square footage. Some of it undoubtedly will have to be measured by hand. A laser distance-measurement tool will speed up this activity. By obtaining and using a facility floor map, ES professionals can check off and ensure that they have covered each room and space. If each patient room is somewhat identical, ES professionals may only need to measure one room, and then copy that square footage onto the map for the other rooms. This process can be used for restrooms, offices, nurses’ stations, treatment rooms and other rooms in which the square footage is identical.

While performing these space measurements, ES professionals should make sure to jot down the type of space classification so that it can be matched with the productivity standard for those areas. Also, remember to note the frequency the area measured will be cleaned (i.e., once per day, twice per day, staffed 24 hours), or if it is a lock-in area.

By knowing the cleanable square footage and the productivity standard associated with the space classification, ES managers are ready to calculate the work time needed to clean those spaces at the assigned frequency.

Add all “like space” square footages together. When the total square footage for a specific category has been calculated, such as patient rooms for a particular hospital location, divide the total square footage by the productivity standard to get the hours needed to clean that space.

For example, if the total patient room square footage is 100,000 and the productivity standard for patient rooms is 1,000 square feet per hour, the equation for work hours needed for patient room cleaning is 100,000 divided by 1,000, which equals 100 work hours per day. The work hours per day would be 200 if the rooms are cleaned twice per day. To calculate the weekly hours, ES professionals simply multiply by seven, for a total of 700 hours. Thus, the facility would need 700 work hours per week just for patient room cleaning.

After the manager completes this workload study to learn the total work hours needed for patient room cleaning, the same process is continued for each space category and measured cleanable square footage.

Another aspect of building workloads for staffing is to identify required work performed per volume. An example of this is patient room cleaning for discharges or transfers. Instead of calculating square footage, actual volume of work performed is calculated. The hospital’s finance department or bed management department can provide the ES manager with a total number of discharges and transfers, usually by day, week, month or year.

The work hours calculation would follow that if there are 75 discharges or transfers per day over a 24-hour period and discharge cleaning in the facility averages 45 minutes each (or .75 hours), 75 multiplied by .75 would equal 56.25 work hours per day, or 393.75 work hours per week. These hours are added to the workload study being compiled to identify the total departmental staffing hours required.

|

| These productivity standards are estimated averages and managers should validate any standard used according to the ability of their assigned staffs. While this can be used as a general guide, all times will vary slightly according to fixtures and furnishings. |

Finally, there are the lock-in and core staffing positions to be considered that must be manned regardless of square footage or volumes. For example, the ED may require housekeeping to be staffed by one housekeeper each shift (24/7). This requires 168 work hours per week. Another example might be for the trash collection job. Having a supervisor or lead run the job for a day or two will provide a good example of the staffing time needed, but a general standard is 2.5 minutes for each room that needs to have trash pulled and 15 minutes to empty each trash holding room.

Floor care productivity is measured according to the standard listed previously or by the time per square foot as measured through experience of the supervisor and managers. A rule of thumb is that floor care jobs are staffed at one floor care position for every 10.5 general housekeeping staff. Basing floor care staffing from productivity standards and square footage will provide a more accurate result.

When calculating time of staff available to work, it should be noted that staff working an eight-hour shift, are not actually working the entire eight hours. If they take 30 minutes for lunch, and two 15-minute breaks, that leaves seven hours of working time available. Allowing 15 minutes for cart setup and 15 minutes for teardown leaves 6.5 total hours per day for each housekeeper in actual productive work time.

Once the manager has combined the total work hours needed, the building of schedules and workloads can begin. Breaking up each area of the facility and its associated work hours needed, then dividing into 6.5-hour work increments (available work hours from each eight-hour staff member) provides the manager with a full allotment of work schedules and full-time equivalent employees needed for the department.

In the field

Michael Burke, manager of ES at North Memorial Medical Center in Robbinsdale, Minn., says he measures productivity for discharge cleaning of patient rooms by square footage and allowed work time. He allows 25 minutes for cleaning a 250-square-foot patient room and 30 minutes for cleaning a 300-square-foot room. He also notes that his department cleans between cases in the operating room (OR) as well as performs end-of-day terminal cleaning. The OR cleaning follows Association of periOperative Registered Nurses standards for cleaning and is based on total surgeries performed. North Memorial ES will look at the total number of surgeries scheduled at the beginning of the day and schedule staff according to the number of cases and rooms assigned. Burke says the department looks to flex its staffing each day according to volumes, and the days of fixed staffing have gone away.

David Maffeo, senior director of support services at Boston Medical Center, says his staff creates a service-level agreement for each department that identifies the level of cleaning that will be completed and has been accounted for in their staffing equation. He also has finalized a unitization process to develop workloads and schedules. By sticking to service-level agreements, clinical staff stay focused on completing their core job functions and ES is allowed to manage the work hours needed based on agreed-upon standards at this large facility. They also have created discharge teams to focus on just completing discharge and transfer cleaning duties. The unitization allowed Maffeo’s staff to know exactly how many work hours were needed for the discharge teams.

David Roberson, CHESP, owner of ProClean Healthcare Consulting LLC, Nashville, Tenn., has been a senior-level ES executive for much of his career. “Technology has made great strides in all areas of ES, particularly the ES staffing and operations software that now automates what had been a pencil-and-paper operation,” he says. However, he cautions about diving into software programs and inputting data without fully understanding the process behind what the software is calculating. Bad information input will result in a poor productivity output, he says. Roberson has found that AHE and ISSA are great resources for productivity standards and cleaning times.

Long-term commitment

The process of unitizing a facility and characterizing all of the data is a test of endurance and stamina. Specific challenges are identified ahead of time that no doubt will arise and need to be addressed with adjustments being made. Mini-goals or achievements along the way are celebrated and the focus eventually turns to the accomplishment associated with completing the process.

Many look for shortcuts and an easier way but, ultimately, end up with an inferior product. If the team can endure the challenges of gathering and processing the productivity data, the manager not only will be successful in developing an efficiently run department, but will have the knowledge to respond to any future changes in scope or requests for reductions.

Rock Jensen is senior consultant at Soriant Healthcare, Milton, Ga. He can be reached at rock.jensen@sorianthealthcare.com.