The art of design and compliance

Planning and design for the UW Health Eastpark Medical Center, a 480,000-square-foot ambulatory facility that includes 29 multi-specialty clinics and one of the world’s first proton therapy treatment centers, employed a repeatable and scalable modular planning and design approach based on the UW Health design standards and guidelines.

Image courtesy of UW Health

In the complex world of health care design and delivery, communicating project intent and requirements across a multidisciplinary group can be challenging. The use of accepted codes, standards and guidelines provides a measure of security and protection. However, these terms can be confusing, and their differences are not always clear.

At the heart of codes, standards and guidelines is a recognition of the need for safety, predictability and consistency. Reducing uncertainty is an important method of reducing risk. Familiar and predictable systems and components can be used to categorize and quantify risk, providing tremendous value to stakeholders engaged in the design and construction of health care facilities.

To correctly apply codes, standards and guidelines, project teams need to have a thorough understanding of the nuanced differences.

Codes, standards and guidelines

Codes, standards and guidelines aid in creating a common language with which to transfer ideas. The development of codes follows formal, prescribed, transparent and regular processes. Internal organizational standards or industry-prescribed guidelines may be created and revised through similar but less stringent processes. A closer examination follows:

Codes. These are regulatory requirements designed to limit opportunities for negative health and safety impacts to a building’s occupants. They are a comprehensive set of guidance intended to become law. Historically, codes were developed and applied locally or regionally, with codes created across regions often having similar goals but different requirements. A regional approach often led to a confusing patchwork of regulations for health care systems and designers whose projects stretched across multiple jurisdictions.

Massive efforts by many organizations have been made to unify minimum requirements nationally. In the case of health care design, the federal government led the development of a national health care design standard in the late 1940s. Over time, this standard became the Facility Guidelines Institute’s (FGI’s) Guidelines for Design and Construction documents for health and residential care facilities. The Guidelines documents are adopted as code by individual states and federal government agencies, which creates some regulatory confusion. They will be renamed the FGI Facility Code in their next edition (see sidebar on page 48).

Standards. This is a term of art and should be understood in context. Regulatory standards (e.g., the National Fire Protection Association’s NFPA 13, Standard for the Installation of Sprinkler Systems) are typically created by an industry with specialized expertise and a deep understanding of how a particular system works.

A standard could tell exactly how to implement or install a building component, but it might not tell where or when it is required to be installed. On the other hand, design standards are nonregulatory and developed by private entities that desire a certain level of standardization within their organizations. A design standard sets a specific expectation (e.g., size, layout or product) and often exceeds code requirements.

- Guidelines. Like design standards, guidelines are nonregulatory and often developed by private or industry organizations that seek to create a base level of standardization. Guidelines are normally understood as guidance documents that exceed the minimum requirements of a code. Thus, the FGI Guidelines are not a true guidance document but a code.

Owner standards and guidelines

Today, many owners have developed their own design standards and guidelines with support from the architecture and engineering professions. Depending on the scale of the owner’s organization, some have evolved to become quite sophisticated. The benefit of these standards and guidelines is systemization, which can provide better project delivery, reduced operational and life-cycle costs, and a more supportive care environment. Some examples include:

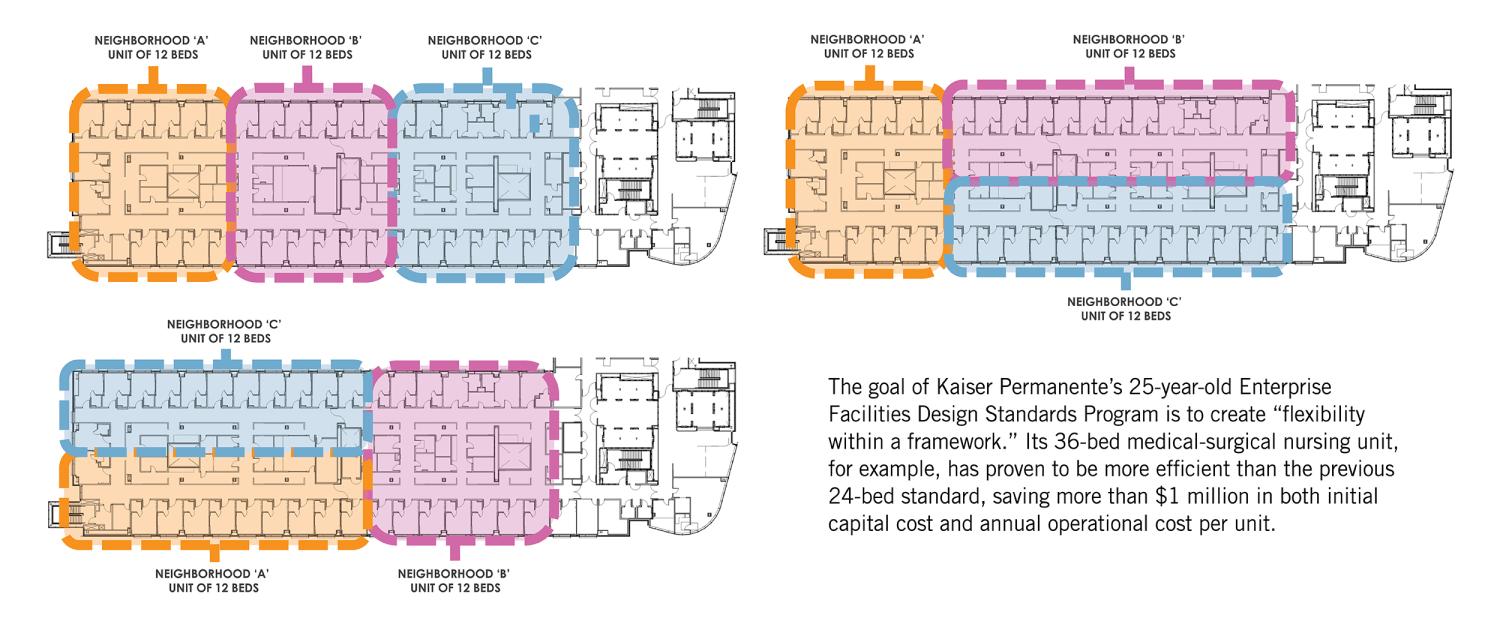

Kaiser Permanente in Oakland, Calif. Kaiser Permanente is a leader in health care innovation and affordability, and its Enterprise Facilities Design Standards Program is a testament to this commitment. Established more than 25 years ago, the program’s aim is to create “flexibility within a framework” that enables innovation in health care delivery.

The program has matured significantly since its inception. It started with clinical rooms and department templates to standardize hospital and medical office buildings; technical design requirements, including information technology and security criteria; building envelope requirements; and energy policies and processes to optimize utilization and carbon neutrality. These standard building blocks provide a consistent level of affordability, sustainability and branding and enable a singular Kaiser Permanente experience for members and staff.

Kaiser Permanente now has more than 100 clinical departments with inpatient and outpatient standards. Content expert panels (CEPs) composed of more than 1,000 clinicians and members establish criteria for optimal operations and care experience and provide research to inform facility design. In addition, Kaiser Permanente assesses health care trends, benchmarks externally and internally, builds mockups and conducts post-occupancy evaluations to further develop the program. Design standards are updated every three years or as needed by code changes, safety issues and lessons learned.

The inpatient nursing CEP found that a 36-bed medical-surgical nursing unit (an example of which is shown below) is more efficient than the previous 24-bed standard, saving over $1 million in initial capital cost and $1 million in annual operational costs per unit. Longer travel distances were a concern for the 36-bed unit, so 12-bed neighborhoods with optimized workflows and design efficiencies were developed to mitigate the change. These savings underscore the importance of considering efficient operational planning and facility design together.

Another example is the pre-engineered medical office building. This standardized approach allows the organization to accurately predict necessary building components, enabling secure pricing agreements with vendors and reducing future facility costs. By standardizing building components, adjusting the size of inpatient units and leveraging clinical expertise, Kaiser Permanente shows a commitment to operational efficiency and cost control, thus improving patient care and overall affordability.

Effective governance and structure are keys to implementing enterprisewide standards. An interdisciplinary governance council of senior executives oversees decisions on the design standards program, ensuring alignment with Kaiser Permanente’s strategic goals and mission. Every project begins with the standards program, leveraging Kaiser Permanente’s institutional knowledge and best practices.

Bon Secours Mercy Health (BSMH) in Cincinnati. BSMH was created from the merger of two separate systems five years ago. The challenge was not just combining two systems but that 38 hospitals and thousands of points of care were part of other systems before the merger. Therefore, there were many significant design and quality issues from the legacy systems. The focus to date has been on developing guidelines for mechanical, electrical, plumbing and fire protection systems; the exterior envelope; finishes and furniture; and typical floor plans (i.e., “Lego” blocks).

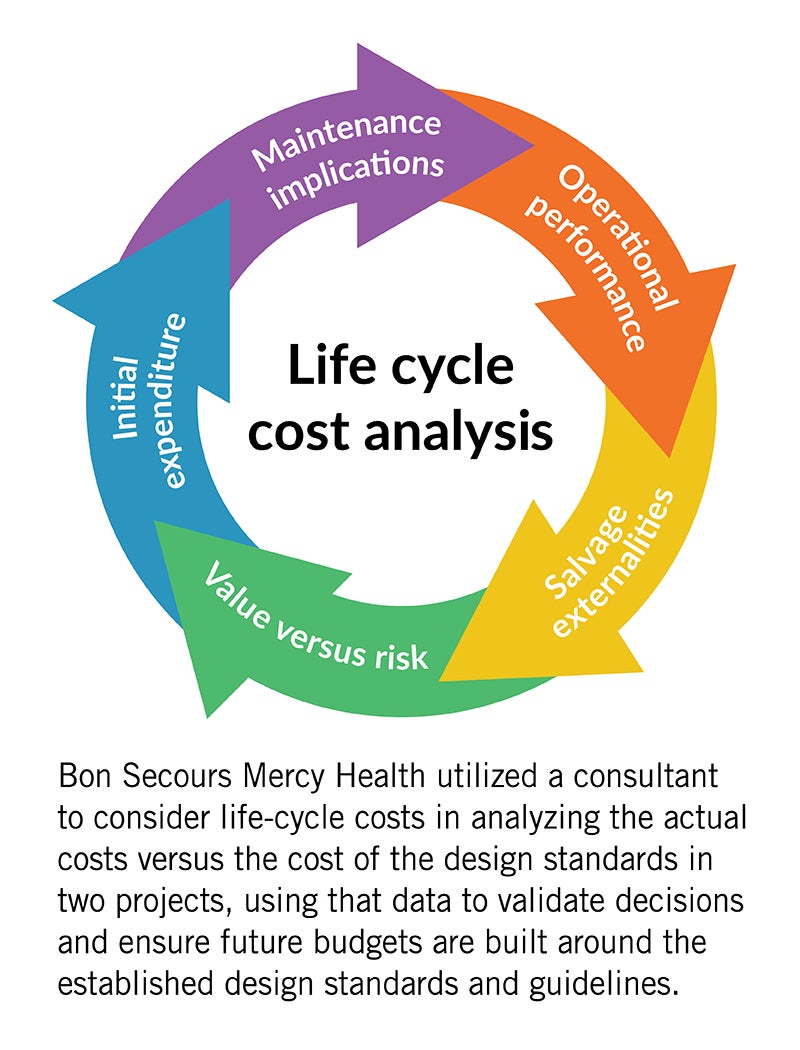

BSMH uses guidelines rather than standards for a specific reason: they are guide rails for the design, not inflexible rules. These guidelines reflect strong preferences and are reevaluated annually. BSMH also has a variance process. A variance committee, consisting of leaders from facilities and administration of the ministry, reviews requests and makes decisions based on data provided, including a life-cycle cost analysis and return on investment (ROI) of the proposed substitute to ensure the most cost-effective designs are being created for the ministry.

Guidelines development centers around systems and design components with the greatest opportunity of optimizing life-cycle costs and developing an ROI to create certainty around what the operations team will maintain. This ensures that first cost is not the only consideration. Historically, a lower first cost has been the focus of design decisions, resulting in annual operating costs that bleed the facility of necessary operating resources.

Another key challenge is developing guidelines related to performance and resiliency, knowing key vendors and partners vary from market to market in large systems with multiple geographic markets. Overall, the guidelines process for these physical environment systems has proven highly successful for a large health care organization spanning a substantial geographic area.

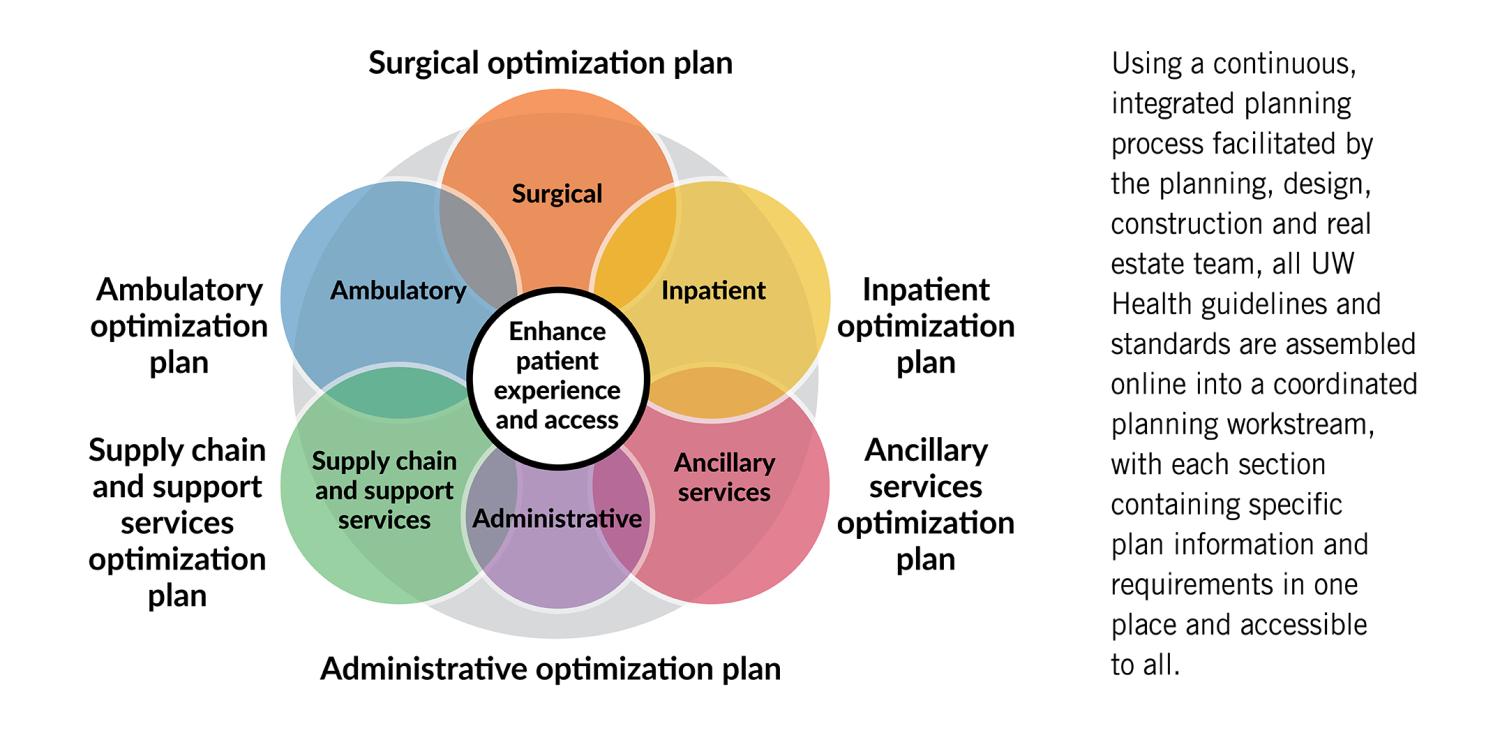

UW Health in Madison, Wis. UW Health’s standards and guidelines focus on supporting workflows and efficient and consistent facility operations. The primary challenge is how to deploy and maintain them across a wide portfolio of facilities that vary in age; planning, design and construction eras; geographic locations; and functional program requirements.

The planning, design, construction and real estate team leads a continuous, integrated planning and design process organized by medical operations planning workstreams, such as surgical, inpatient, ambulatory, ancillary services, facility support services and administrative/research/education. Each workstream continuously works on its optimization plan, which collectively informs the strategic system facilities plan, along with the strategic information systems plan, strategic asset (i.e., major medical equipment) plan and infrastructure plan.

The strategic system facilities plan informs the campus/building comprehensive plans from which the site-specific implementation projects are developed. This entire process informs and supports the organization’s strategic capital plan, typically with a 10-year projection.

The standards and guidelines enforced by the planning, design, construction and real estate team support this process by providing a consistent benchmark to plan, design and budget while also informing the business plans for projects, with known and consistent operating and maintenance costs across the system of care.

Platform for innovation

For the design community, protecting health, safety and welfare is the mantra of building codes, while through specialty building typologies, the spectrum of guidelines and standards varies depending on the mission, vision, functional model and preferred architectural expression of the owners’ technical and functional characteristics.

Owner-specific health care standards and guidelines reflect business models, strategic plans, priorities, operations and maintenance models, and branding. They convey positions on critical topics like paths to net zero, community engagement, research and development, academic engagement, innovation and environmental, social and governance. They also ensure safety, functionality, efficiency and responsive architectural expressions.

Through collaboration and service to many health care systems, architects can see the differences between a systems approach through benchmarking and research, which, when paired with medicine and technological advancements, gives the architect a perspective and voice to inform industry standards. This thought leadership allows for improved outcomes and innovation. To deliver tailored and effective design solutions, the design community can use client-specific guidelines as a framework to provide a stable foundation upon which innovation and creativity can thrive. For contractors, standards enable a different approach to design and construction by promoting streamlined, generative design (e.g., reduced time and cost, improved accuracy and integration). They foster industrialized and “kit-of-parts” approaches, allowing owners to develop supply chain relationships that reduce lead times.

“Standards can be leveraged as a platform for (rather than an inhibitor to) innovation,” states Will Lichtig, chief innovation officer at The Boldt Group in Appleton, Wis. “There is a difference between variation (“we do it differently”) and innovation (“we can do it better”). Standards should capture the current best way, leaving room for future innovation.”

Build and evolve

Central to the ability of managing space across a system of care is having design guidelines and standards. Teams (i.e., architects, interior designers, engineers and contractors) that appreciate and understand the role standards and guidelines play will thrive, bringing value and mitigating risk for the health care organizations they serve. Those who can’t or won’t, choosing instead to hold on to project delivery and project implementation processes of the past, will find themselves on the outside looking in.

Owners are moving to support and enhance this framework with artificial intelligence. Digital libraries that capture and embed relevant data about each standard can be used to “design” the project to provide information about what to use and the “why” behind the standard. Standards and guidelines are captured effectively to promote knowledge-based design.

Design standards and guidelines, coupled with codes, provide more consistent results across multiple projects delivered by various consultants. They consist of regulatory requirements, recommended best practices, current owner preferences, required coordination of multiple disciplines and trades, and common trip points from lessons learned.

As Walt Vernon, CEO of Mazzetti in San Francisco, recalls, “When I was in high school, I got frustrated by grammar rules. One day, I took a William Faulkner book to my English teacher. I read her one sentence that spanned ... at least two pages and violated every rule of grammar ... I asked her why, if the world’s greatest writers got rewarded for flaunting grammar rules, I needed to follow these rules. This wise person told me a writer like Faulkner could do what he did because he understood the rules, why they existed and how to appropriately go beyond them. That is, the rules were not a prison; they were a foundation. I have carried this philosophy with me ever since. All of which is to say that standards, like grammar rules, have a serious purpose and benefit, but the art comes from knowing how and when to build on them and evolve them.”

If managed well, standards will improve outcomes for patients; enhance the patient, family and visitor experience; improve the staff experience; support more effective workflows; reinforce the organization’s brand and brand experience; and improve project delivery. They are not an affront to planning and design but a crucial framework and necessary set of tools.

RELATED ARTICLE: Upcoming FGI Facility Code

Multidisciplinary groups, such as the Facility Guidelines Institute’s (FGI’s) Health Guidelines Revision Committee, invest thousands of hours in creating a “translatory bridge” between different disciplines. A thoughtful code development process requires a broad diversity of reviewers and commentators from all phases of the project and care delivery process. It also involves periods of deep reflection on lessons learned and future purpose and intent.

The FGI’s Guidelines documents have been a conundrum for many professionals because they’re actually not guidelines but codes. To strengthen the understanding and application of these documents, the 2026 edition will be renamed the FGI Facility Code. Further, it will no longer feature any guidance text (i.e., appendices).

Text formerly included in the appendices will appear in a new series of handbooks that are under development. The handbooks will feature expanded design guidance, including best practices, tools, checklists and graphics created in collaboration with subject matter experts. The handbooks will enable FGI to provide greater clarity around the intent of the minimum requirements.

About this article

This feature is one of a series of articles published by Health Facilities Management in partnership with The Center for Health Design. Authors for this article are members of The Center’s Built Environment Network (BEN). To learn more about BEN and The Center’s other Environment Networks, visit The Center for Health Design online.

John L. Williams is vice president of content and outreach at the Facility Guidelines Institute; Susana A. Erpestad, AIA, ACHA, LEED AP BD+C, EDAC, is HDR’s global director of federal architecture; Angelene Baldi, EDAC, is Kaiser Permanente’s executive director of facilities planning and design for national facilities design and construction services; Chris Knueven is Bon Secours Mercy Health’s vice president of design and construction; and Michael McKay, AIA, ACHE, EDAC, LEED AP, NCARB, is UW Health’s director of planning, design, construction and real estate. They can be reached at john@fgiguidelines.org, susana.erpestad@hdrinc.com, angelene.baldi@kp.org, cknueven@mercy.com and mmckay@uwhealth.org.